Arsenal footballer Hector Bellerin recently partnered with a reforestation charity and pledged to plant 3,000 trees every time his team won. This is just one example of the now widespread use of celebrities like him in environmental conservation marketing campaigns.

But are such endorsements actually effective? We’re not so sure. For a recent academic study we explored whether the campaigns evaluated the success of these endorsements, and looked for evidence that celebrities helped to achieve campaign objectives.

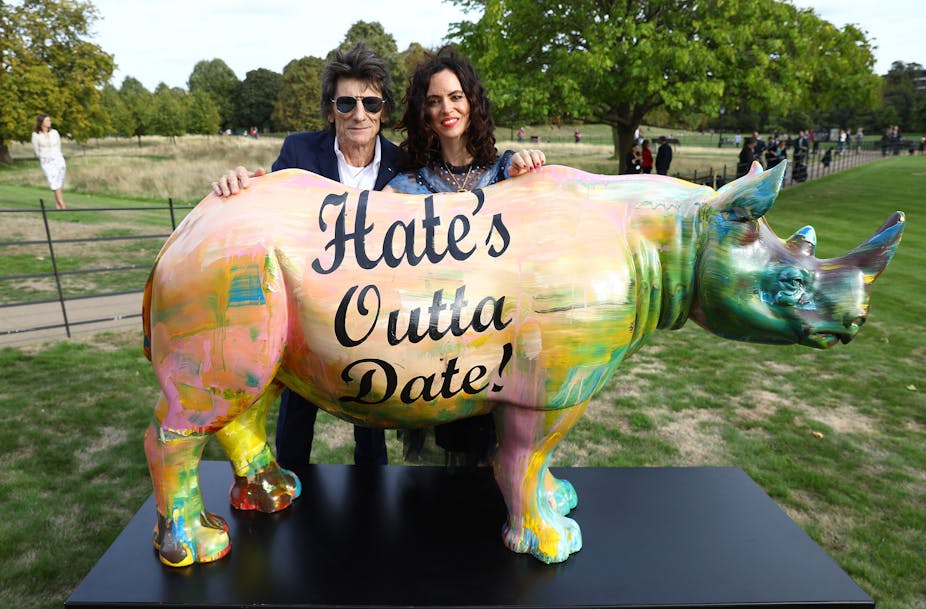

To give us a more global view we searched in six different languages for publications on celebrity-endorsed environment campaigns: English, Chinese, Spanish, Portuguese, French and Vietnamese. We found 79 campaigns implemented in nine countries between 1976 and 2018. In total 181 celebrities endorsed these campaigns. They included actors, musicians, athletes, experts in a particular topic, TV presenters, writers, artists, models, comedians and politicians. Most campaigns focused on sustainable lifestyles and wildlife conservation, while pollution and climate change received limited attention.

To analyse the campaigns, we compared them against an eight-step framework for implementing a celebrity-based intervention that one of us developed in previous research which included elements from the conservation, business and behavioural science literature. The eight steps include ensuring an intervention is informed by research, that it has a clear pathway to its desired objective(s), an evidence-based rationale behind campaign components such as celebrity selection or overall campaign concept, and that it is tested before implementation. These elements allow the campaign organisers – and later researchers like us – to measure its success.

Among the campaigns studied we found a dearth of measurable objectives, theories of change, research into celebrity selection, and evaluation of success. Just 40% of campaigns reported their objectives for enlisting celebrities, and most said it was to get more media coverage.

But campaign visibility should not be an end in itself. Visibility indicates delivery, not whether the messages delivered had the desired impact. A recent example of this was seen when a group of celebrities sang the John Lennon song “Imagine” from their homes during the pandemic. The video had hundreds of thousands of views, but a lot of the comments and reactions the video received were negative.

Only one campaign had a theory of change that guided the development of objectives, target audience selection, campaign design, and celebrity choice. In the marketing field, guiding principles are used to select celebrity messengers. For example, selecting celebrities who are perceived as attractive, trustworthy, or to whom the target audience can relate. Our results indicate these principles are not being applied in environmental campaigns.

The only campaign that reported research into celebrity selection was the United Nations Environmental Program’s (UNEP) #WildforLife campaign. It sought to raise awareness of the illegal wildlife trade in key countries. Relevant demographic groups were identified and local celebrities who the target audience followed on social media were engaged as influencers. The remainder of the campaigns we looked at did not specify why celebrities were enlisted or why their endorsement would contribute to achieving campaign objectives.

Of the 79 campaigns we looked at, only four were evaluated. And these assessments do not show evidence that celebrity endorsement specifically contributed to achieving campaign results. For example, The Target 140 campaign set out to reduce daily water consumption by 20% in Brisbane, Australia. Yes, a 22% reduction in water consumption was achieved. But the evaluation did not provide any insight into whether the celebrities involved contributed to this success.

Despite the lack of evaluation, 11 claims of campaign effectiveness were made and of these, three claimed celebrity endorsement was effective. In one of them, Chinese writers Zhao Danian and Shu Yi encouraged chefs to pledge to abstain from cooking with endangered wildlife. While some pledges were made, there was no information on how many chefs had been approached or how many had accepted or declined to take part. Further, no follow-up on the chefs’ behaviour was reported.

In the #WildforLife campaign, the objectives were to raise awareness of the illegal wildlife trade and mobilise people to protect endangered species and end the trade. While sharing campaign messages through celebrities’ social media accounts achieved the desired reach, it should not be assumed that reach is equivalent to raising awareness and mobilising action. The quality and content of social media reactions to the campaign could have indicated if the audience was responding to the message or to the celebrity, or both, but this was not evaluated.

The lack of measurable objectives, theories of change, outcome indicators, and critical evaluation renders it impossible to determine whether the outcomes achieved by the campaigns found can be attributed to celebrity endorsement. It therefore remains unclear whether celebrity endorsement of environmental campaigns can contribute to environmental protection and conservation efforts.

We found only 79 campaigns in the literature searched for in this scoping review despite searching in six languages from the earliest records available up to January 2019. It is possible, even likely, that data and information demonstrating the effectiveness of celebrity endorsement does exist within campaigning organisations that use celebrities. If so, this is problematic for conservationists because lessons learned cannot be used more widely. Organisations should be encouraged to report the success – or failures – of celebrity endorsements, to ensure that their future use in environmental campaigns is based on evidence.