The intelligence industry is habitually accused of being too embedded in its own protective culture, trade-craft and jargon.

As an antidote to the murky world of intelligence, Revealing Secrets, by academic John Blaxland and distinguished national security expert Clare Birgin, provides a highly comprehensive, well-researched and captivating account of the history and role of Australian Signals intelligence in national security.

Succinct and accessible, it is pitched for readers who care about transparency and security alike, with enough insight into matters such as cyber security developments and digital war games to satisfy computer and technology geeks.

Review: Revealing Secrets: An unofficial history of Australian Signals intelligence & the advent of cyber – John Blaxland and Clare Birgin (UNSW Press)

Signals intelligence or Sigint is about eavesdropping on messages and data. It is the intelligence (or information) gained by the collection and interception of communications and electronic systems that comprise a wide range of “signals” – such as radios, radars, telephone systems and computer networks. It can involve code-breaking and interpretation.

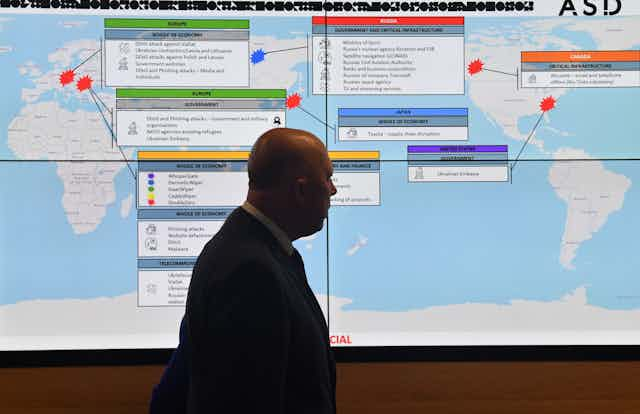

The Australian Signals Directorate, established in 1947 as a signals intelligence and security agency, intercepts communication from countries around the world, learning about the threats and intentions of targets abroad. Its modern-day capabilities – both defensive and offensive – also play an important role in trying to head off cyber attacks against Australia by disrupting offshore, cyber-enabled crime.

Read more: Explainer: how the Australian intelligence community works

But the book, which traverses the two world wars and post-war national and international Sigint arrangements, points out that the directorate is only a part of Australia’s Sigint (and electronic warfare) history.

Such a broad scope provides the reader with an insightful journey through the management and methods of national security affairs. The book unpacks the switch from analogue to digital technology, to the so-called fifth dimension of cyber in modern warfare (which exists alongside sea, land, air and space).

It covers controversies such as the value of Pine Gap’s shared intelligence arrangements with the United States (Pine Gap is a joint Sigint facility located in central Australia) and explores the government’s ongoing efforts to understand or assess the capabilities, intentions or activities of foreign adversaries.

Revealing Secrets commemorates past intelligence accomplishments (and reflects on failures) while stimulating debate on modern-day intelligence systems in an information age. Subjects explored include crypt-analysis – the study of encrypted text and messages – and the evolution of machinery to aid such deciphering.

There is also an acknowledgement of gender biases in this field. In the 1940s, for instance, there was a reluctance to employ skilled female telegraphists in the army despite the shortage of code-breaking male counterparts.

Poorly understood

Broadly speaking, the intelligence function involves the collection, analysis and dissemination of information to support decision-making. This intelligence may have been intercepted from the electronic signals and systems of a particular target, such as a coded enemy message.

Yet as Blaxland has previously noted, signals intelligence has repeatedly been portrayed as the “poor cousin” of human intelligence and other forms of data.

One persistent dilemma is the role and impact of signals intelligence is highly tricky for the general public to access or comprehend. Much of what the directorate does, for instance, is highly classified. Yet the provision of signals intelligence is often mooted by policymakers and defence planners as an indispensable secret asset for tactical and strategic intelligence.

In short, much of the history of Sigint intelligence – revealing secrets and protecting one’s own – is tacit and poorly understood. Indeed, for a long time, the role and increasingly intrusive powers of Sigint tended to be overlooked, or the subject of speculation.

Read more: Beyond spy balloons: here are 7 kinds of intelligence spies want, and how they get it

In 2013, whistle-blower Edward Snowden notoriously exposed the existence of previously classified mass intelligence-gathering surveillance programs run by the US National Security Agency.

The authors of this book acknowledge the intelligence dump about agency’s surveillance net did “cast a long shadow” and caused “great citizen concern about the trustworthiness of national security institutions with vast and potentially intrusive powers”.

Paradoxically, the Snowden leaks may have inadvertently coaxed many Western governments to be more secret and less open – although such an instinct could also attributed to other concurrent political happenings.

Even so, one area in which this book excels is in “opening the door” to a deeper appreciation of Australia’s role in global events. Operations have included sabotaging enemy communications and denying the Islamic State (also known as ISIS) the ability to connect to the internet – from a base in Canberra – to give cover to Iraqi and partner troops in the Middle East.

Revealing Secrets also reveals how signals intelligence has influenced major diplomatic actions and defence design.

For instance, the decoding of the German Zimmerman telegram by British cryptographers in 1917 helped to draw the US into the first world war. In the 1930s, Sigint was used to tackle Germany’s Enigma code – the breaking of German communication messaging within their armed forces by Allied parties. Signals intelligence was valuable during military campaigns in second world war and Cold War–era operations in locations like Malaya, Borneo and Vietnam.

The book is filled with noteworthy Australian historical characters, such as electrical engineer Florence Violet McKenzie, who, along with her husband Cecil, founded the Women’s Emergency Signalling Corps in 1939 to provide signals training to women.

Controversies

Clearly UK and US ties have significantly helped shape Australia’s Sigint capabilities, albeit with benefits and pitfalls. The authors shrewdly capture various controversial aspects of the use and goals of intelligence. They include the Australian government’s A$9.9 billion REDSPICE project, announced last year, which pledged to double the directorate’s workforce and increase its protective and offensive cyber capabilities as part of Australia’s “cyber deterence” posture.

Whether Australia should use offensive cyber capabilities against other actors and, if so, against who, remains highly contentious. This ambitious project has raised many unanswered questions about what “offensive” digital capabilities and “cyber-hunt activities” might entail. There are potential ramifications with regard to domestic and international law, as well as the norms of good international behaviour.

The authors conclude there are considerable advantages to retaining a joint facility such as Pine Gap. It can assist with arms control verification and provide early warning of missile launches. But the overall pros and cons of Australia’s investment in intelligence infrastructure shared with the US feed into debates about sovereignty, dependency and how future security goals with the US might differ.

The book guides readers through a shadowy side of government, reflecting on legal implications and ethical dilemmas. Australia’s regulation of electronic surveillance remains highly complex and convoluted. Intelligence functions and powers are often blurred within a hyper-legislative context and are declared, the authors write, without “[…] a clear explanation of what is being done and why it is being done”.

The expansion of covert surveillance and data interception within law enforcement and various intelligence agencies has sparked debate about human rights implications here. Australia does not have a Bill of Rights, unlike most other similar liberal democracies.

‘Not all Australians are the good guys’

The book shows various misinterpretations and misconstructions of Sigint can be explained, in part, due to its highly specialised nature and the concealment necessary to maintain operational effectiveness.

There has also been a reluctance by outsiders to write about Sigint because they do not have access to all the facts about the rationale and workings of electronic eavesdropping, the breakneck speed of technology and intricacies of communications in statecraft.

The authors hope that their book will act as “[…] a preview, or ‘taster’, pointing to where further research is needed […]”.

Such a framing is timely given the directorate’s director-general, Rachel Noble, has defended the need to collect intelligence on Australians for Sigint and cyber security operations. “Not all Australians,” she has said, “are the good guys”. Noble has clarified that the directorate cannot, under law, conduct mass surveillance on Australians.

Intelligence does play a substantial role in efforts to better identify and investigate potential threats, avoiding strategic surprise and defending core national interests. And by explaining various facets of Australian Sigint, the book advances the logic that security-planners need to be prepared and forward-thinking in dealing with threat assessments. The history of Sigint itself does reveal the quality and usefulness of the intelligence to support foreign policy and defence preparedness.

It is by no means unreasonable for intelligence agencies to wish to preserve sensitive technical capabilities. But conversely the public do except a high standard of apolitical conduct in “speaking truth to power”. The actions of all agencies must be properly scrutinised.

Digital spying and privacy intrusions should be proportionate and justifiable, balanced with democratic safeguards and adequate checks and balances. In short, snooping on everyone because you can does not mean you should. At its heart, the book is both a reminder of the merits and virtues of actionable intelligence and arguments for checks and balances on government error and excess.

Despite the inherent vulnerabilities of interconnected cyber-space networks to hacking and exploitation, cloak-and-dagger policies make it hard to know if we are prioritising astute budget commitments and directing resources to the right strategies.

Interestingly, Revealing Secrets was originally commissioned (at a cost of $2.2 million) by the former head of the directorate. It was abruptly shelved due to what Noble later described as “the balance of the content”.

Despite not having privileged access to official secret records, Revealing Secrets is a comprehensive deep-dive, bringing to life to previously unmapped archival information and drawing upon both an impressive quantity of associated open-source material.

Blaxland and Bergin have produced a high quality and clear-eyed piece of scholarship, offering a sweeping authoritative historical perspective on one of the most secret branches of Australian intelligence.