Many of us are aware of the environmental crisis, and the need to change how we operate. On a daily basis, a variety of media offer images that depict the effects of climate change to help us understand the extent of environmental damage — for example, in the form of scientists’ endless data and metrics presented in graphs or in news photographs.

Visual imagery has been central to how people develop a sense of the meaning of the Anthropocene — the era we are living in, the first time that human activity is the dominant influence on climate.

In the past few decades, new practices of art, design and architecture in the public realm have helped raise awareness about ubiquitous waste, pollution and global warming, and their associated social injustices.

With my colleagues, I am cataloguing public art, design and architecture projects in Canada that aim to teach about the environmental crisis, to reveal what eco-lessons are conveyed to the public and what the public can learn. Our work is informed by drawing on art and design that has helped launch both expert and community dialogue about what kinds of visual imagery and artistic practices might engender positive action for our environment.

Green arithmetic

Environmental historian and professor of sociology Jason W. Moore has explored how environmental researchers and policy makers have aimed to help the public understand how global warming is affecting Earth through data and metrics about environmental change — what he calls “green arithmetic.”

Even if these quantifiable methods of representation have been a powerful model for understanding the “what” of our planetary condition, it’s unclear if people have understood the effects of the present crisis on biological and socio-economic aspects of our interconnected world — or what changes we need to change course.

Graphical charts show exponential damages, but who can understand what a kilogram of carbon dioxide is or what it does to the environment? This format of visual imagery is far too abstract and the information depicted is set at a scale that is difficult for many to imagine.

As T.J. Demos, professor of art history and visual culture, has argued, graphs developed by environmental organizations or researchers rarely motivate people to take positive environmental action.

Sublime images of catastrophe

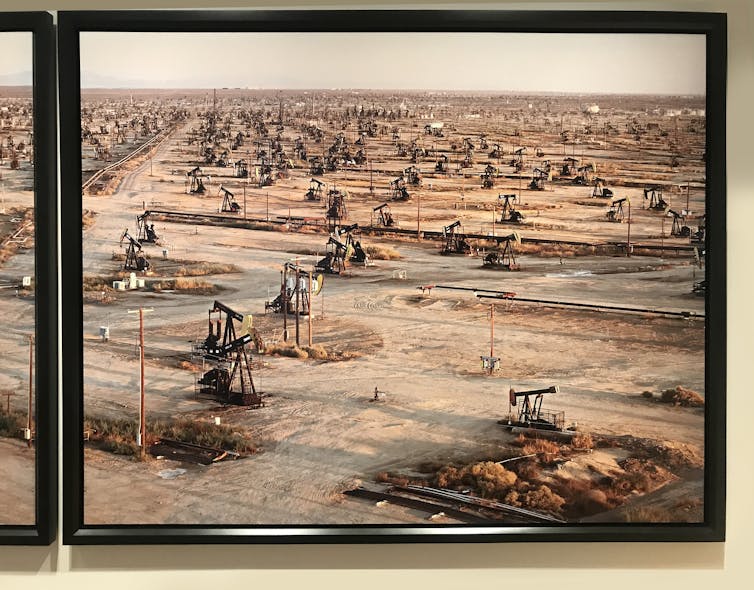

Some artists have created sublime imagery depicting situations of catastrophe. Photographer Edward Burtynsky and other artists have developed artistic investigations that tell stories that reflect on what environmental transformation means.

Photographer J. Henry Fair is another artist who uses magnificent pictures to document “the hidden costs of consumption.”

This type of art is often placed in museums, which in most cases, isn’t an open public space. And only a small portion of the population ever sets foot into a museum.

However, it is not only museums that exhibit such images. Media outlets reaching the general public sometimes share photos about climate change disasters that they package as “beautiful” and “stunning.”

Such images may indeed be “stunning.” The problem is, however, that such pictures, whether generated by professional artists, photojournalists or by people sharing on creative forums, are often so sublimely produced that audiences want to consume more of them. Yet, there isn’t much certainty that this will help raise awareness of real causes of environmental damage, let alone engender change. These types of artworks, which can become highly popular cultural products, may be counterproductive to the aim of enabling change.

Public eco-art installations

On the other hand, the public art installation Ice Watch by Icelandic Danish artist Olafur Eliasson, first created in 2014, was a seminal work intended to provoke immediate responses to our ecological crisis.

In the words of the artist, this work saw: “12 large blocks of ice cast off from the Greenland ice sheet are harvested from a fjord outside Nuuk and presented in a clock formation in a prominent public place.”

In its second installation, the work was placed in front of the Place du Pantheon in Paris in 2015, when an international meeting on climate change, COP21, was taking place.

The installation was simple, yet it made climate change immediately felt for those present, as people could see and touch the massive chunks of melting ice. It also connected people all around the world through its Instagram feed.

A statement about the artwork noted that the ice sheet from which these blocks were harvested is “losing the equivalent of 1,000 such blocks of ice per second throughout the year.” There were no graphs showing data about melting glaciers. Yet witnesses had a resonating experience about climate catastrophe.

The installation helped people confront the environmental crisis in a direct and personal way, since people saw, as writer Rebecca Solnit noted, a “beautiful, disturbing, dying monument.” A feeling of dread and eco-anxiety is at the core of this experience, a concept termed “solastalgia,” in 2005 by professor of sustainability Glenn Albrecht.

Public digital art

Another example is Particle Falls, by digital media artist Andrea Polli. This work was first publicly projected in 2010 and has been shown in a variety of places, including Philadelphia in 2013.

Particle Falls projects a visualization of air pollution data of the surrounding area and projects this as a waterfall. When the waterfall is calm, the air pollution is low. When pollution is high, the waterfall resembles an agitated boiling sludge seeping down the side of the building. Anyone walking on the city streets can encounter this visualization and be directly affected since it displays real-time data that can be seen and acted on.

Getting to systemic change

These public works are successful in their capacity to make catastrophic situations, which are invisible to most people, visible. They may even activate some small behaviour changes.

Are such creations successful in empowering systemic change? Combining real-time data with visceral experiences in public spaces is a first step. Perhaps the ability to also deeply engage civic society in these public works may enable the necessary transformational changes.

Eco-art and design projects in public spaces are about offering powerful experiences to passersby and where they become witnesses to a devastating world situation. Through these experiences, people move a step closer to situations they may otherwise not have been able to imagine. And, having imagined these situations, people may then perhaps be motivated to solve them.