In an apparent attempt to “talk across the political divide”, former chancellor George Osborne and former shadow chancellor Ed Balls have launched a podcast.

Political Currency has been billed as a behind-the-scenes glimpse into the rooms and minds where the key decisions are made. But what is perhaps more evident from the opening episodes is not how politicians of different parties can communicate so much as how they can collude.

It hasn’t taken long for the two men to use the podcast to celebrate their joint achievements. This began with the current Labour party “sticking with the two-child limit on welfare, which I [Osborne] introduced.”

Balls’s response was telling:

Well, that takes you to an interesting thing in British politics which is that in the end, however contested things are, the only things that last are the things that become consensual. So, the Conservatives opposed the minimum wage in 1997, you [Osborne] ended up boasting about raising it. The Conservatives opposed Central Bank independence in 97/98, you ended up being a champion of it. The trade union reforms of the 1980s, which many Labour People hated at the time – clearly Tony Blair and Gordon Brown carried on with them. So, things which are contested can become consensual and when people agree, that is often how our county moves forward.

Issues on which Balls and Osborne appear to happily agree have so far included setting a very low minimum wage for huge numbers of workers and greatly curtailing the ability of trade unions to protest and organise.

Those of us who listened on learnt how cross-party consensus was achieved in Westminster on the policy to restrict benefits so that parents can only claim support for two children – not a third or any subsequent child.

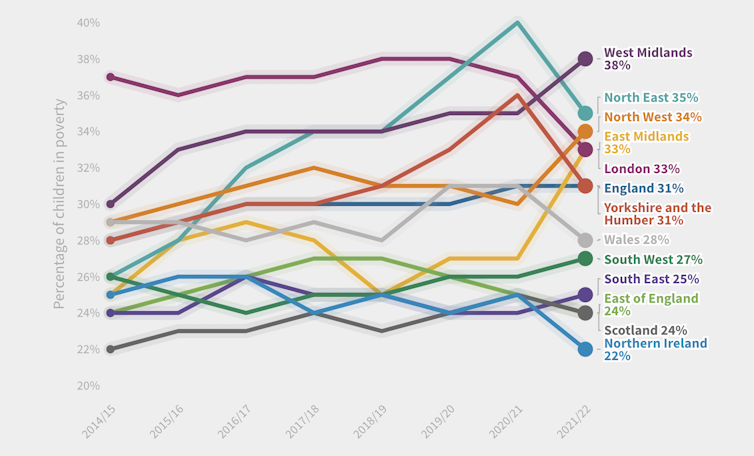

This policy has been a key driver of child poverty in England and Wales, where a majority of children who have two or more siblings go hungry several times a month. The policy does not apply in Scotland and Northern Ireland, which are now the two places in the UK where child poverty rates are lowest.

And yet poverty itself has so far only been mentioned once on the podcast, around halfway through episode one. Even then, our hosts were talking about pensioner poverty – an issue that matters, they explained, because so many votes are involved.

In the same episode, Osborne revealed how the New Labour and Conservative parties had colluded (or “worked together”, as he put it) to “see the state pension age go from 65, to 66, to 67, to 68”. He continued with another example of how key issues were agreed by both sides rather than being put to the electorate:

I remember Peter Mandelson coming to me before the 2010 general election, he was the [Labour] deputy prime minister, and saying “we want to put up student fees, tuition fees, but we can’t do that before an election, its too difficult for Labour, why don’t we set up a report, and while you as Conservatives hopefully want to see the tuition fees go up so that the universities are better funded, why don’t you sign up to this commission and it can report after the election?”

Balls agreed that this was the right way to go about things, that the two main political parties of the UK should agree policy between themselves, as the “grown-ups in the room” while ensuring that it appeared as if each election mattered.

The two men appear to agree on almost everything of any substance. Or if they don’t, they’ll work out their differences between themselves and tell us the result later.

Listen to the ‘grown-ups’

So far, Balls and Osborne have been in a celebratory mood in their discussions. They appear very happy with the current state of British politics and the people in charge. There is much bile disguised as banter.

Both have particular contempt for Boris Johnson, Ed Miliband and Jeremy Corbyn, with most of their anger directed at Miliband, who they linked, at length and unfairly, to Russell Brand. They both disagree with Brexit but accept it. For them, in 2023, the grown-ups are back in charge again – and that includes their gaining air time.

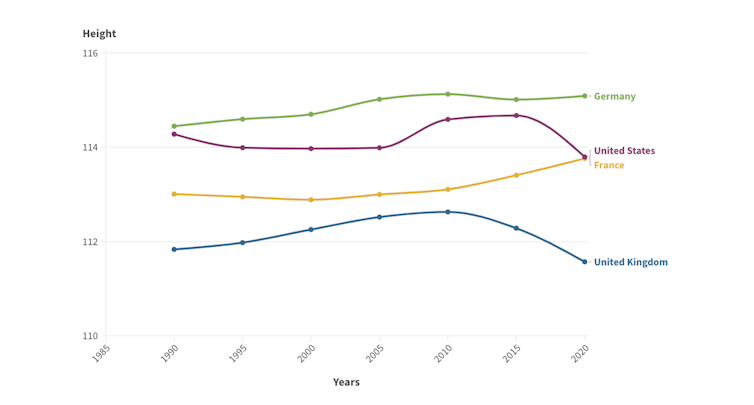

Listening to them, I’ve thought of how the austerity policies they speak about have led to deprivation in the UK on such a scale that many children no longer grow up properly, physically or mentally. How the average height of five-year-old boys in the UK has risen and fallen since 1990.

Average height of five-year-old boys, 1990-2020:

If Balls or Osborne have an explanation other than child deprivation for the above trends, it would be interesting to hear it. The most convincing explanation I have heard as to why we have tolerated such high inequality and poverty in the UK for so long was reportedly given at a private dinner in Hampshire in 2002, when Margaret Thatcher was asked what her greatest achievement had been. She replied: “Tony Blair and New Labour. We forced our opponents to change their minds.”

There is an older parallel to be drawn, too. In 1940, three journalists of three different political persuasions wrote a book together: The Guilty Men. They were Michael Foot, Peter Howard and Frank Owen and their targets were the British public figures who appeased 1930s Germany.

A similar book could be written today about the appeasers of market forces who promised that we could live with “tough decisions” under austerity and that children would not go hungry or grow up stunted.

But instead we have the two-men-talking-to-each-other podcast format. In every episode, Balls and Osborne happily outline the thinking behind their actions – the actions that just a few in my generation, given the best starts in life, have taken and have caused such harm to others.

I am grateful to them for using their show to put so much on the record about their time in charge, years before their cabinet papers and other secret documents will be released to the public.