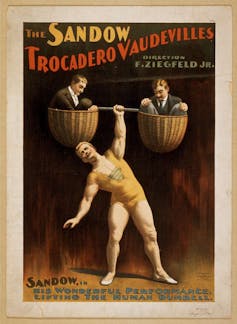

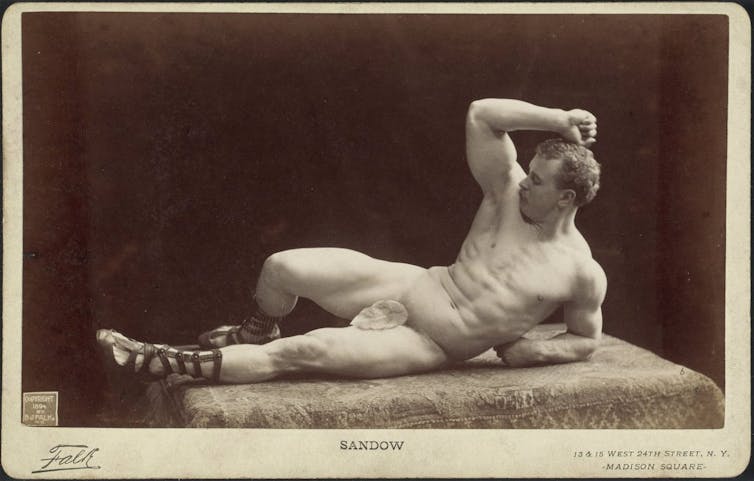

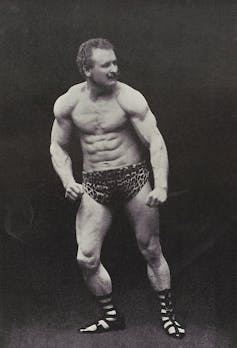

Eugen Sandow was an internationally famous strongman. The German-born British showman (1867-1925) toured the world challenging other strongmen and staging displays of strength. He declared himself to be a physical culturist and became the face of the physical culture movement and a pioneer of bodybuilding. Historically, the term “physical culture” is associated with displays of strength, health and fitness.

On 25 May 1904 – 120 years ago – Sandow began a tour of colonial South Africa. He left in September for Mozambique where he gave two performances and then set sail for India, China and Japan. His South African visit marked a high point of colonial imperial display and was steeped in racism.

Read more: How colonial history shaped bodies and sport at the edges of empire

Scholars have argued that Sandow, born Frederich Mueller, took his English name from the term “eugenics”. Eugenics is the flawed, racist “science” of genetic racial improvement that was also adopted during the Nazi era in Germany, in America and Great Britain. Sandow arrived in South Africa following the international shock of Britain’s difficulties during the long and expensive South African War against the Afrikaners (Boers). He supported British eugenic efforts to “improve” the English race.

Just a year before Sandow arrived in South Africa, the British Lions rugby team had visited the region in what was sometimes billed as a “tour of reconciliation” between England and the defeated Afrikaner nation.

As he did in other places, Sandow left behind the seeds of a revival of the strongman cult in South Africa through his stage shows and writings. He had become the representation of what was understood to be the ideal, strong, white Englishman and many emulated him.

But only one academic paper exists about Sandow’s charged visit to South Africa. My study of archival materials shows that the visit marked a (mostly invisible) web between pedagogy (teaching), entertainment and colonial prejudices. I argue that “Sandowism” was an unintended propaganda tool for British imperialism, with Sandow playing a part in laying a foundation for later discrimination in sport in the country.

Sandow and the colonial project

Sandow’s shows marked a shift in the country’s physical culture entertainment industry. Any future would-be strongmen who depended on brute strength alone fell by the wayside after him. Sandow brought theatricality to these displays, as well as a belief in the health benefits of strongman culture.

He fostered a new (white) audience for physical culture events. One newspaper reported that his show was:

A full house, composed principally of ladies and children.

His performances were spectacular. Towards the end of his tour, another newspaper reported:

Sandow continues nightly to amaze, delight, and instruct the crowds by his graceful movements, his statuesque poses, and his Samson-like exhibitions of strength.

In South Africa he also wrote opinion pieces, directed at women, on subjects like skincare and corsets. (He believed that women should build their physiques instead of relying on corsets to strengthen their bodies.) In the US, women paid considerable sums for private interviews in his dressing room after his shows.

Sandow’s South African visit drew attention to a new phenomenon – professional physical culture entertainment (similar to what we see in staged strength and wrestling events on television today). The support Sandow received from the South African medical, educational and organised sport fraternity also helped popularise his visit.

His tour of South Africa was entwined with capitalism, nationalist politics, Edwardian sexuality, sport coaching and controversy. It was part of his venture to return to England with a troupe of performers from 30 different nations with which he intended to astonish audiences through physical culture displays.

Physical culture

Physical culture originated in the 1800s as a health and strength training movement. The study of physical culture, the foundation of body building and weightlifting, is extremely neglected in the global south. Yet, this field of study reveals much about how human beings use exercise, medicine and sport to shape their lives.

Sandow’s physical culture programme conformed with beliefs promoted by sport scientists at the time, such as Dudley Sergent from Harvard University. They believed that women were best suited for sports like golf, horse-riding and tennis.

Sandow’s influence in South Africa

A School of Physical Culture would open in Johannesburg in 1904, claiming to originate from Sandow, though he denied the claim. The same year, a newspaper advertisement offered the “Sandow system: Special classes for ladies only” conducted by a trained pupil of Sandow.

Before Sandow’s arrival, public displays by strongmen were not unknown in South African society. One example is that of Kupido Kok, a cousin of the Griqua leader, Adam Kok. His reported feats included snapping the thigh bone of an eland, lifting a large pot from a fire with his little finger and lifting a 5,000 pound wagon. However, his skills did not interest colonial societies, where whiteness mattered above all. This was reinforced in physical culture by displays like Sandow’s body – its whiteness emphasised on stage with powders and lighting.

Yet, as my study outlines, Sandow’s influence would play a role in promoting body building and weightlifting among black South Africans.

An early known account of a connection between Sandow and South Africa was when white South African-born strongman, author and business entrepreneur Tromp van Diggelen visited his consulting rooms in 1897 in England. He remained inspired by Sandow for the rest of his life. During his lifetime, Van Diggelen was a popular figure in black South African communities and advertised his training programmes in the local black press.

Van Diggelen also assisted the black South African weightlifter Ron Eland to travel to England to qualify for the Olympic Games in 1948. In turn, Eland was partly responsible for promoting the bodybuilding career of the black South African David Isaacs, who gained an international footprint.

Lost to history

Today, with the rise of scientific sports studies, physical culture has all but disappeared from public consciousness in Africa.

At the time, though, Sandow claimed that physical culture had developed into an exact science and he even examined potential South African pupils medically. To date however, physical education, sport science and medical exercise historians have ignored Sandow’s influence on their field of study in South Africa.

Read more: The story of Milo Pillay, the strongman who lifted a bar for South African sports

Sadly, this means a loss of understanding of the historical roots of racism in weightlifting, bodybuilding and exercise medicine in the country.