Almost everyone will know someone with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): an incurable disease of the lungs that makes breathing difficult.

Never heard of it? Well, chances are you’ve heard of “smoker’s lung”, emphysema or chronic bronchitis – all of which fall under the umbrella term COPD.

Causes and prevalence

According to the World Health Organization, 64 million people worldwide have COPD. And while the prevalence varies from country to country, around one in every 13 Australians over the age of 40 have the illness.

COPD essentially develops as a result of long-term exposure to airborne toxins. Across the western world, the main risk factor is exposure to cigarette smoke. However it’s a slightly different story in developing countries, where years of exposure to biomass fuel smoke (wood smoke, for example, from cooking or indoor heating) is an important cause in people who do not smoke cigarettes.

Even so, COPD related to cigarette smoking is projected to increase in the developing world, as smoking rates continue to increase to alarmingly high levels. By the latest estimates, more than 30% of 11- to 15-year-old children smoke in some parts of Africa.

The WHO estimates that, without intervention to cut risks, the total number of COPD deaths will increase by 30% over the next ten years.

Harmful effects

The toxic effects of cigarette smoke reach far into the lungs, affecting almost every part of them to varying degrees.

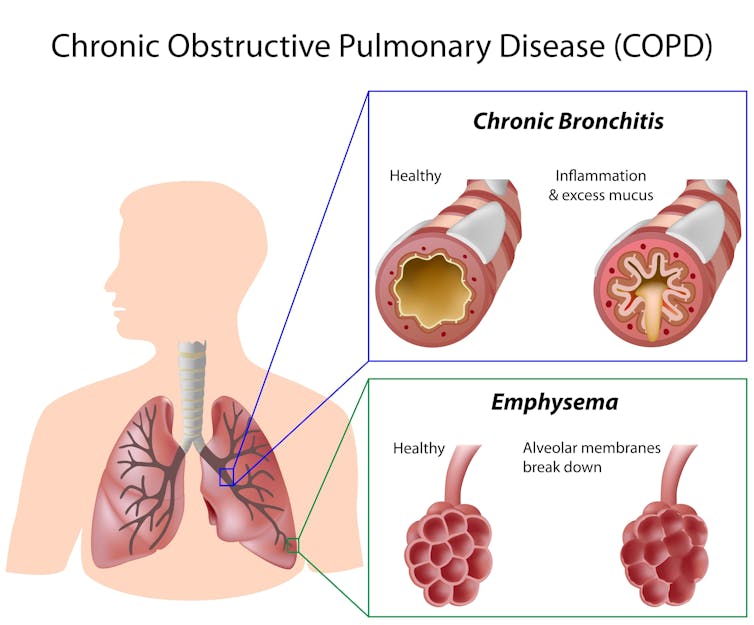

A person with COPD may have inflammation and narrowing of their airways (bronchitis). They may have destruction of the lung’s tiny air sacs, with holes scattered throughout their lungs like Swiss cheese (emphysema). Most likely, they have a combination of both.

It probably matters little to a person with COPD precisely what pathological processes are brewing inside their chest, since they all contribute to the same debilitating symptom: breathlessness.

The lungs are not the only part of the body affected in this disease. COPD is also associated with disorders of the cardiovascular system, weight loss, muscle wasting and chronic inflammation.

Even in Australia, COPD can occur in people who have never smoked a cigarette in their lives. In these people, the cause may not be quite as apparent. It may be the result of occupational exposures (to dusts or fumes, for instance), or the presence of other lung diseases such as long-standing asthma or tuberculosis (although COPD develops only in a minority of people with these conditions).

Even more elusive is the cause of COPD in people who have no identifiable risk factors at all. Genes probably play an important role in these cases.

Therapies

Despite this dire portrait of COPD, treatments are available. Generally speaking, treatment starts with inhaled medications that open up the airways, known as bronchodilators. Some people require the addition of anti-inflammatory medications such as steroids.

Clinicians often prescribe non-medical therapies such as pulmonary rehabilitation – a tailored, supervised exercise program for people with lung disease. At the extreme end, some people may be offered a lung transplant, although in Australia this is quite rare.

Obviously, advice and support on smoking cessation is an important part of any treatment plan, and is essential at all stages of the disease.

But most of these therapies have been around for many years. So where are we headed?

Future treatment

The future of COPD treatment really is as varied as scientists’ imagination. Most proposed new therapies target inflammation. Other research focuses on developing better bronchodilator medications, decreasing the size of each drug molecule to deliver it deeper into the lungs.

A more novel approach to treating COPD is to design therapies that essentially rebuild the lungs.

The biggest problem in treating COPD is that current treatments cannot replace the missing lung tissue, and this has lead some researchers to propose that stem cell therapy may be a viable treatment option. As exciting as this may sound, it is likely to be many more years before such therapy makes it into clinical practice.

Despite research into new therapies, when it comes to COPD, prevention is still better than cure. Australia has long been a world leader in tobacco control, an accolade we can be proud of. The hard part will be maintaining momentum and avoiding complacency as smoking rates decline.

Research needs to continue into effective education and control measures, so that COPD might one day be relegated to the history books rather than top of the list of preventable lifestyle diseases.