Public participation in science is increasing, and citizen science has a central part in this. It is a contribution by the public to research, actively undertaken and requiring thoughtful action.

Citizen science projects involve non-professionals taking part in crowdsourcing, data analysis, and data collection. The idea is to break down big tasks into understandable components that anyone can perform.

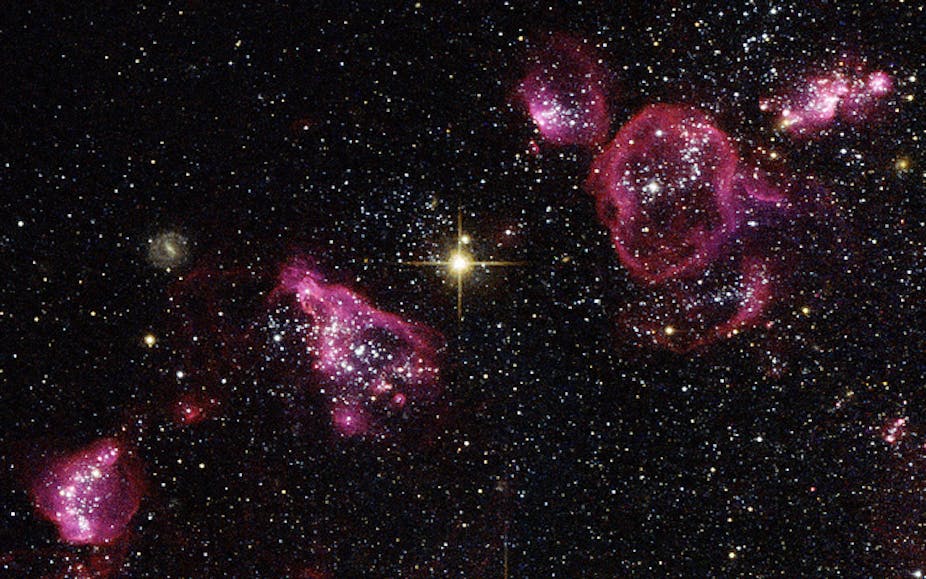

One of the largest examples of this is Zooniverse, a website I work on that at any one time runs multiple science projects. Users can pick any project they like the look of – from helping to understand how galaxies form, to classifying years of tropical cyclone data, to analysing real life cancer data. Subject areas of research range between space, climate, humanities, nature, and biology. Anyone can contribute to these crucial areas of research by classifying pictures or data.

Zooniverse has a community of more than 850,000 people, who have taken part in more than 20 citizen science projects over the years. In the last year alone, people collectively spent just shy of half a million hours working on these projects. This amounts to one person spending 52 years analysing data.

Good citizen science projects are usually designed after a lot of thought. For example, Zooniverse rarely gives the public abstract problems and always try to keep context in frame. The aim is to allow the users to get valuable results, and slowly most citizen science projects are doing just that.

The users of Fold.it solve puzzles in order to advance knowledge about protein structures, something which is key to understanding how they work, and how to target them with drugs. Eyewire also advertises itself as a game, where users “map the brain” and discover neural connections, advancing neuroscience research on how the retina functions in visual perception. eBird is a crowdsourced data collection project, whose users record the birds they see, contributing to conservation. Randomise Me allows you to set up your own mass-participation data collection project.

In all these cases, people know what they’re taking part in. The Blackawton Bees paper is a perfect example of citizen science that was both data collection and analysis - in this case, by children. Pupils from Blackawton Primary School studied the behaviour of bees, and their findings were accepted for publication in the Royal Society’s Biology Letters Journal.

Above all, citizen science demonstrates that people want to make a contribution to science. It is easy to understand why people want to make a meaningful donation of their time, and heartening that this is the case.

We have learned that on the web, participation is unequal, with the distribution of effort in our own projects being comparable to projects like Wikipedia or Twitter. Most users on Zooinverse do little and some users do staggering amounts, but as long as the numbers are large that doesn’t matter.

The aim of citizen science ought to be to undertake research and discovery. That is surely wrapped up in its definition as a subset of science. It is not outreach or education – which our sites are often confused with in academia.

The web is a sophisticated place and a well designed citizen science site can go far and do a lot of good work. Sadly, it is also possible for a site to attract a lot of attention but never do anything useful at all. Of paramount importance is the concept of authenticity. Genuine participation in science is essential in an era when such a thing is possible. We should never waste people’s time. Now that it has been convincingly shown that the public can contribute to research via the web, it is incumbent on new web-based projects to keep the bar raised and the standard high.

We are at the beginning of a citizen science renaissance online. After hundreds of years, beyond the purview of bug-collectors and bird-watchers (all very important work, I hasten to add), we are finally able to tap into the cognitive surplus - the population’s free time - and attempt truly distributed research.

This is a modified version of a post that was first published on Robert Simpson’s blog