Why do people migrate? At first glance it seems reasonable to assume that most people move hoping to find better conditions or opportunities elsewhere, such as jobs, higher wages, safety or freedom of expression. This is the implicit assumption underlying the most popular theories of migration.

But while few researchers would contest that most migrants have good reasons to move, this does not really help us understand what really drives migration. To say that most people migrate to find better opportunities is somehow stating the obvious. Migration is seen as a (temporary) response to differences in development between people’s own countries and a desired destination, that will decline as wages and conditions converge. But this view ignores that migration has been a constant factor in the history of humankind and can therefore not be reduced to a temporary by-product of capitalist development.

These models fail to give insight into the social, economic and political processes that have created the wage and opportunity gaps to which migration is supposedly a response and are actually at odds with what is seen in real-life migration patterns. For instance, most migrants do not move from the poorest to the wealthiest countries, and the poorest countries tend to have lower levels of emigration than middle-income and wealthier countries.

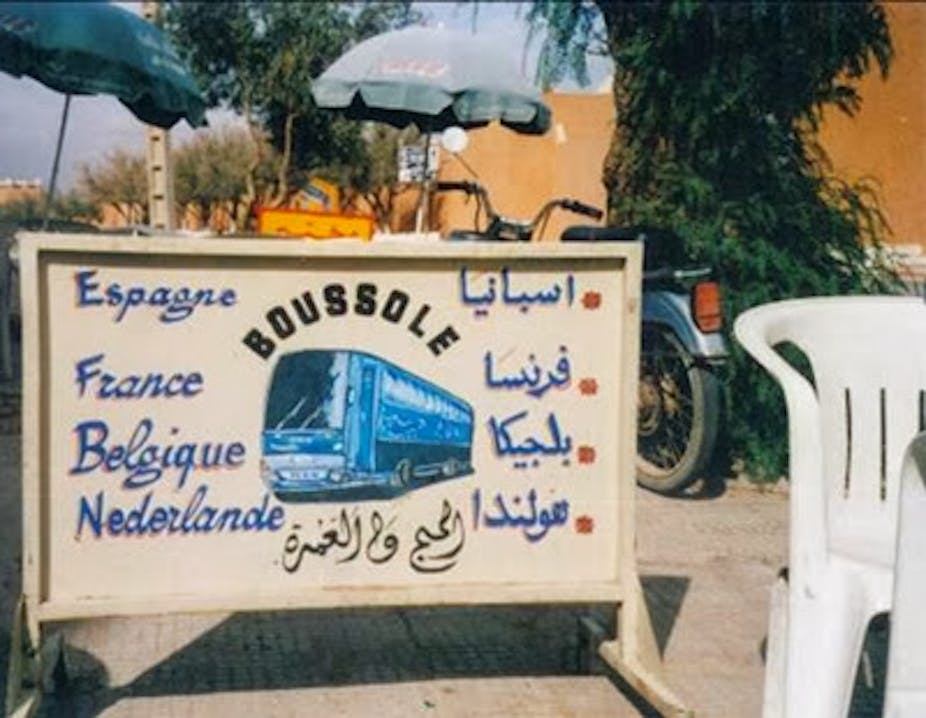

It is often said that the only way to reduce migration from poor countries is to boost development, but this ignores the inconvenient fact that development is generally not associated with lower levels of emigration. Important emigration countries such as Mexico, Morocco, Turkey and the Philippines are typically not among the poorest countries. Meanwhile – and against popular perceptions of a “continent on the move” – Sub-Saharan Africa is the least migratory region of the world.

Development drives migration

In fact, when you examine the data, human and economic development is initially associated with increasing emigration. Any form of development in the poorest countries of the world is therefore likely to lead to accelerating emigration. Such findings contradict conventional thinking and force us to radically change our views on migration. Such rethinking can be achieved by learning to see migration as an intrinsic part of broader development processes rather than as a problem to be solved, or the temporary response to development “disequilibria”.

For instance, in the modern age, much migration within and across borders has been inextricably linked to broader urbanisation processes. It is difficult to imagine urbanisation without migration, and vice-versa. Rather than asking “why people migrate” – which often begs a simple, all-too-obvious and often quite meaningless answer – the more relevant question for understanding migration in the modern age is therefore how processes such as imperialism, nation state formation, the industrial revolution, capitalist development, urbanisation and globalisation change migration patterns and migrants’ experiences.

For instance, how can we explain why development is often associated with more, instead of less, migration? To understand this, it is important to move beyond sterile views of migrants as entirely predictable “respondents” to geographical opportunity gaps. Seeing migration as a function of people’s capabilities and aspirations to move can help to achieve a richer understanding of migration behaviour.

Processes of human and economic development typically expand people’s access to material resources, social networks and knowledge. At the same time, improvements in infrastructure and transportation, which usually accompany development, make travel less costly and risky. It therefore seems safe to assume that development generally increases people’s capabilities to migrate over larger distances. However, this does not necessarily lead to migration. People will generally only migrate if they have the aspirations to do so.

Looking for the good life

Migration aspirations depend on people’s more general life aspirations, as well as their perceptions of life “here” and “there”. Improved access to information, images and lifestyles conveyed through education and media tend to broaden people’s mental horizons, change their perceptions of the “good life” and typically increase material aspirations. Development processes tend to initially increase both people’s ability to move and their aspirations, explaining why development often boosts migration.

Once sizeable migrant communities have settled, social networks tend to reduce the costs and risks of migrating, with settled migrants frequently functioning as “bridgeheads”. When societies get wealthier, more people can imagine a future within their own country and they are less likely to emigrate – while immigration is likely to increase.

In modern times, technological progress has certainly meant people are able to move around more, without necessarily migrating. So we see more commuting, tourism and business travel. But the impact of progress on migration is rather ambiguous. Although it is often assumed that technological progress increases migration, easier transportation and communication may enable people to commute or work from home, while outsourcing and trade may also reduce the need to migrate. This may partly explain why the number of international migrants as a share of the world population has remained remarkably stable at levels of around 3% over recent decades. Nevertheless, wealthy countries remain characterised by substantial levels of migration. We see significant migration even between societies with roughly equal levels of development and wages.

This can partly be explained by increasing educational and occupational specialisation, which often accompanies economic development and requires people to move within and across borders to match their qualifications and preferences with labour market and social opportunities. The higher skilled therefore tend to migrate more and over larger distances. This shows that it is an illusion to think that large-scale migration is somehow a temporary phenomenon that will disappear with development.

More generally, such ideas reflect a flawed, ahistorical view on the history of humankind. It is development itself that drives migration. Migration has therefore always been – and will remain – an inevitable part of the human experience.

This is an edited version of an article that first appeared on Hein de Haas’ blog.