We need to get the Muslim community itself to sign up to the Prevent programme. Only one out of eight referrals to Prevent come from within the Muslim community.

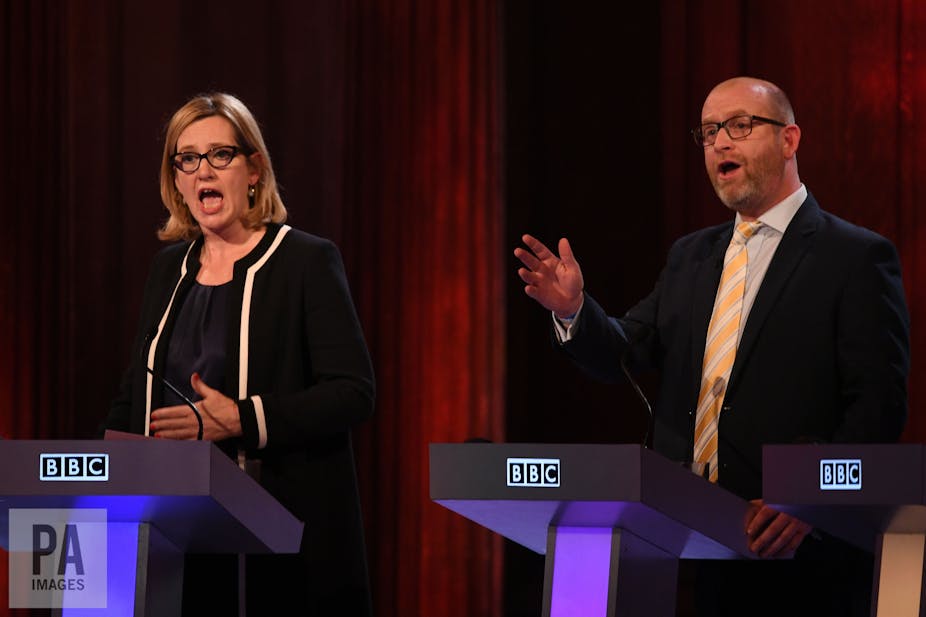

Paul Nuttall, leader of UKIP, speaking during the BBC Election Debate on May 31.

Paul Nuttall’s comment about the number of referrals under the government’s counter-terrorism strategy, Prevent, used a statistic that was incorrectly quoted and dropped into the debate without context. The only publicly available statistic – quoted in The Times and The Guardian in December 2015 – stated that out of 3,288 referrals to the Prevent programme in the first half of 2015, only 280 or 8.6% came from within the Muslim “community, family, friends and faith leaders”. Using Nuttall’s comparison, this would make it one in 12 referrals.

The figures were provided by the National Police Chief’s Council (NPCC) in response to a freedom of information request and refer to the first half of 2015. They are not official published government data. Other information is held by the Home Office on the gender, age, ethnicity and religion of people arrested under counter-terrorism legislation, but it does not publish data on those who make the referrals.

When I asked the NPCC, its press office stated that: “Those figures were given out under freedom of information requests” – but the information provided cannot be found on the relevant part of its website.

It should also be noted that referrals are made in line with Prevent legislation to the police, MI5, and on the online anti-extremism website, and not to what Nuttall calls the “Prevent programme”. If an individual is deemed vulnerable to all types of extremism and terrorism, they may be referred to what’s called the Channel programme. Between 2007 and 2014, other data published by the NPCC indicates there have been a total of 3,934 referrals to Channel and that 56% of those referred between April 2012 and March 2014 were recorded as Muslims.

UKIP were contacted twice for comment by The Conversation about Nuttall’s claim, but didn’t respond.

Missing context

Nuttall’s claim also misses much of the context surrounding the available statistics. It is not clear how the religion of the person making the referral to the Prevent programme was determined. The Times article assumes that “community, family and friends” will be, by default, Muslims. However, use of the terms “community” and “friends” indicates a wider pool of informants.

The statistics also have to be considered within the context of the number of Muslims that can potentially report radicalisation, extremism and terrorism. If 8.6% of all referrals did come from the local community, this represents a high number of reports coming from the Muslim population, as the 2011 census states that Muslims make up only 5% of the British population.

But looking at the number of referrals made to the Prevent programme is not indicative of its success or failure. Salman Abedi, who detonated a suicide bomb in Manchester in late May, was reported to authorities on several occasions by members of his community and friends, but this did not prevent the attack. Further focus needs to be placed on the intelligence processes.

However, there has been a marked deterioration in attitudes towards the Prevent strategy. A 2011 NPCC report stated that “Muslims welcome engagement”, but increasing terror attacks have caused some to question Prevent amid claims it is targeting Muslims.

Another NPCC research report on counter-terrorism published in January 2017 highlighted concerns raised by Muslims and other ethnic minorities over anonymity and fear of unfair treatment by the police. Growing disdain has been shown for the continuing need for the Muslim population to apologise for terrorist attacks, when the rise of the far-right has not stimulated the same response.

Verdict

The statistics quoted by Nuttall are incorrect, misleading and divisive. By claiming that Muslims are not doing enough he implies that the Muslim population knows more than they are letting on and are able to do something about it. This is not an internal problem for Muslims alone. Placing the responsibility of reporting suspicion on the Muslim population demonises them and makes them the only actors responsible for stopping future attacks.

Understanding that Muslims – like any other group, religious or secular – are part of the larger population will help to contextualise any statistics provided on their participation in counter-terrorism programmes. Assumptions that the Muslim community is cohesive and aware of the actions of every other Muslim must also be dispelled.

Review

Sarah Marsden, lecturer in politics, philosophy and religion, University of Lancaster

The author is right to point out the difficulty in unpacking the statistics on the Prevent policy and its implementation. A primary source of information on Prevent referrals comes from freedom of information requests. These respond to specific queries rather than systematically reporting data. This makes it difficult to make sense of a complex picture, and allows people like Paul Nuttall to make political capital against a backdrop of unclear information.

Nevertheless, there are more up-to-date figures than the article suggests. More recent statistics suggest that as many as 10,250 people have been referred to Channel between 2007 and March 2016. Approximately 70% of these are for what is defined as “international (Islamist) extremism”. Of these, the majority have been referred by statutory bodies, and notably, over 4,800 have come from the education sector. However, it is not clear what role individuals outside of these institutions play in what is a maturing system for managing Channel referrals. For example, a parent may tell the person at a school who is responsible for Prevent that they are concerned about a child. The referral may then be taken forward by the school, but its origin would have been from a member of the community.

But the author is right to challenge the assumptions that sit beneath Nuttall’s criticism of Muslim communities. Placing responsibility for reporting those who may be involved in terrorism with Muslim communities is deeply divisive. It overlooks the responsibility we all share to prevent terrorism, and the not insignificant challenges facing efforts to identify those who may be “at risk” of radicalisation. It also risks stigmatising Muslims, many of whom are distrustful of Prevent because of the perception that it unfairly targets their communities. Indeed, this scepticism may be a more powerful explanation for reporting patterns than any unwillingness to take responsibility for community safety.