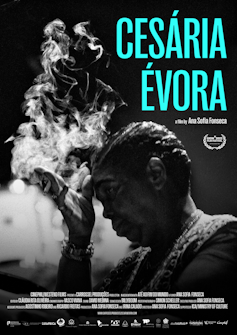

Ana Sofia Fonseca’s feature documentary Cesária Évora opens with hand-held, bootleg-style footage of the legendary Cabo Verdean morna singer in rehearsal. It is visually inauspicious but subtly heralds the film’s great strength. An intimate approach that illuminates Évora’s extraordinary career while staying close to her personal struggles and triumphs.

The combination of the Portuguese director and journalist Fonseca’s storytelling and editor Cláudia Rita Oliveira’s organisation of myriad archival resources results in a film that will fascinate both devoted fans as well as those encountering Évora’s biography for the first time.

Good music documentaries are often about more than the music, or even the basic biographies of the musicians. Cesária shares a little with Searching for Sugar Man (2012) about 1970s rock singer Rodriguez. Both central characters are shy, and overwhelmed at times by the nature of their fame. As one character muses in Cesária, “How would she survive her success?”

Cesária Évora and Cabo Verde

Cesária Évora died in 2011. She was born in 1941 in the tiny port town of Mindelo on the island of São Vicente, part of the archipelago of Cabo Verde in West Africa. She was a natural performer and singer for many years before her breakthrough albums were recorded in her fifties. The film moves back and forth in time, setting her burgeoning international fame in the context of her very humble beginnings singing in bars around Mindelo.

Fonseca also uses these retrospective sequences to reflect on the experience of Cabo Verdeans under the dying days of Portuguese colonialism. To provide the context for Évora’s early years, Fonseca digitally rejuvenates damaged archival footage of the Portuguese navy from the 1960s and reportage of the early days of independence.

This mixture of old formats, including celluloid, tape, still images, voice interviews and concert footage creates an increasingly textured film. It situates Évora in the histories of not only Portuguese colonialism and Cabo Verdean independence, but also the ‘World Music’ movement. And, of course, African music. Morna – the style particular to Cabo Verde – is a globally recognised sound largely because of Évora.

In an interview Fonseca discusses how hard it was to find old footage of Évora and to track down people who could shed light on her years of performing in Mindelo and her decade of self-imposed isolation. Fonseca’s patient, investigative approach yields a narrative of discovery for viewers.

Behind the scenes

Behind-the-scenes footage in a music documentary is always fascinating. Here Évora’s fans bring her a pot of cachupa (a traditional Cabo Verdean stew) before her performance at the Hollywood Bowl. Her wry and mischievous sense of humour sparkles in the scenes where she sings with legendary singer Compay Segundo in Cuba. What starts as a disharmonious scene between the ageing legends ends in ribald asides and laughter.

Évora is an intuitive, gifted singer, and like her, the film also follows a free-wheeling style that hits the right notes. From typical tour bus scenes – band members sleeping sprawled on every available surface – to limousine rides in New York, the film tracks her on a punishing schedule of international tours, from Portland, Oregon to Siberia and most places in between, including the obligatory television appearance on Letterman.

Barefoot diva

But she always returns home to Mindelo, to her household of family, friends and strangers offered a meal. Indeed, food is an understated but persistent theme throughout the film. Évora is a queen to Cabo Verdeans, particularly those on São Vicente, as well as those in the diaspora who meet her at her concerts all around the world.

In spite of the considerable fame which Évora attained late in her life, she remained, in the words of one interviewee, an “anti-star”. She was dubbed ‘the barefoot diva’ for appearing without shoes on stage. She was not barefoot for effect, or as a marketing ploy, but because normal Cabo Verdeans “don’t like to wear shoes”.

There were no concessions to popular trends in her music. Her songs remained a bewitching blend of insouciant sensuality, tenderness and melancholy. As she says to an interviewer in response to a question regarding her global renown:

As a person, I am the same person.

Listening to Cesária Évora, I am struck by her amazing ability to find and to make spaces between the notes. There is a casual yet exhilarating precision and feel in the melodic lines that recalls singer Aretha Franklin, and a tone echoing singer Billie Holiday, and yet Évora sounds like no-one else. In a lovely scene towards the end of the film she shuffles around her house singing some lines spontaneously for a guest, and her voice has the same extraordinary quality as it does on stage during her live performances.

The film’s final scenes follow the more typical biopic line, preparing us for the inevitably of Évora’s passing with a montage of bleak poetic shots of Cabo Verde’s volcanic landscapes. Fonseca’s rhythmical return to the plains and mountains of São Vicente is a reminder of Évora’s love for home, and a metaphor for a voice that is both angelic and from the earth.

Cesária Évora is showing at the Encounters South African International Documentary Festival in Johannesburg on 1 July