The world is falling behind on commitments to protect and restore forests, according to the recent Forest Declaration Assessment. There is no serious pathway to fixing climate change while forest losses continue at current rates, because global climate targets, sustainable development goals and forest commitments depend on each other.

But it isn’t too late. The Assessment was published alongside the Forest Pathways Report I led for conservation organisation the WWF, which sets out a blueprint for how we turn our global forest failures around and get on track to protected, restored and sustainably managed forests.

Around 1.6 billion people live close enough to forests to depend upon them for their livelihoods, and forests suck down about a third of our CO₂ emissions from fossil fuels.

The UN estimates that forests directly generate US$250 billion (£206 billion) in economic activity a year. Their broader, indirect, value might be as much as US$150 trillion (£12 trillion) per year – double the value of global stocks – largely due to their ability to store carbon. Despite this, subsidies still provide incentives for people to convert forests into agriculture.

Failing promises

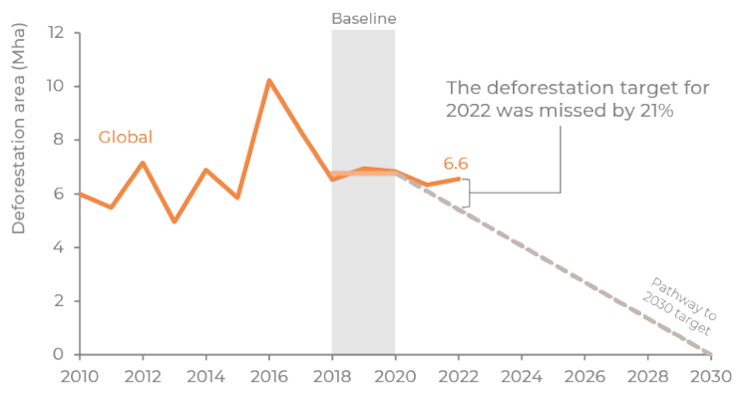

There have been multiple global commitments to forests, with hundreds of governments and businesses signing up to pledges named after cities they were signed in: Bonn in 2011, New York in 2014, Glasgow in 2021. But these pledges have not been realised, and deforestation reduction targets are slipping each year.

Global forest loss in 2022 was 6.6 million hectares, an area about the size of Ireland. That’s 21% more than the amount that would keep us on track to meet the target of zero deforestation by 2030, agreed in Glasgow. The loss of tropical rainforest is even more pronounced: 33% over the target needed. Deforestation in 2022 marked a 4% step back on 2021 progress.

Why we are failing to protect forests

There isn’t one simple explanation for why forests are still disappearing. Factors include a lack of Indigenous Peoples rights to their territories, forest-harming financial and trade systems, and the physical effects of climate change and fire.

The lack of consistent and secure land tenure rights for Indigenous Peoples and local communities threatens forests and the people who depend upon them. Across the tropics, where forests are under their stewardship, the evidence is clear: deforestation and degradation are lower.

Subsidies that can lead to deforestation are worth between US$381 billion (£314 billion) and US$1 trillion (£825 billion) per year. These could include handing out public land to settlers, building roads or pipes to enable industrial-scale farming, keeping taxes on agricultural products artificially low, or subsidies on specific crops grown on formerly forested lands.

There are also illegal activities. By one recent estimate, 69% of the tropical forest cleared for agriculture between 2013 and 2019 violated national laws and regulations. The illegal timber trade is estimated to be worth US$150 billion per year globally.

There is simply not enough money going to support forests. Public finance for forests is less than 1% “”) of the amount invested in activities that are environmentally harmful or incentivise deforestation.

Around the globe, forests are also being harmed by climate change and shifting patterns of wildfires. Climate change is causing more fires, including in forests that do not usually burn, and producing hotter fires which cause long-term damage even in fire-adapted forests. The length and severity of droughts is increasing, inducing water stress which kills trees. A combination of climate-related stresses means that trees in the tropics, temperate and boreal forests, are experiencing dying younger and massive “die offs” are happening more often.

If the effects of fire and climate change continue post-Anthropocene forests are likely to be smaller, simpler in species, emptied of wildlife and restricted to steeper ground where agriculture is less favoured.

Computer simulations of the future climate, known as climate models, depict very different outcomes for forests depending on whether we limit global warming or not. If emissions are reigned in and we leave some cultivated land to nature, 350 million hectares of forest could return by 2100. That’s an area roughly the size of India. However, in a future where emissions remain high and land use doesn’t change, the models suggest a loss of a further 500 million hectares of forest by 2100.

Back on track

The new Forest Pathways Report I worked on sets out an action plan for getting back on track. It asks global leaders and businesses to:

Accelerate the recognition of Indigenous Peoples and local communities’ right to own and manage their lands, territories and resources.

Provide more money, both public and private, to support sustainable forest economies.

Reform the rules of global trade that harm forests, getting deforesting commodities out of global supply chains, and removing barriers to forest-friendly goods.

Shift towards nature-based and bio economies.

At the next COP28 climate summit in Dubai, there is the promise of bilateral announcements between wealthy donor nations and forested nations in the tropics, as part of the Forest and Climate Leaders’ Partnership signed in Glasgow, two years ago. These packages could support a move towards sustainable forest management and deforestation-free supply chains around the world.

This would be a valuable success, but leadership is desperately needed on other issues such as environmentally harmful subsidies or illegal logging, the financial scale of which both dwarf the funding provided to protect forests.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 20,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.