Top French officials, including French President Charles de Gaulle, sought to conduct atmospheric nuclear tests in the Algerian Sahara following the former French colony’s independence in 1962. These plans, described in recently declassified French documents, never came to fruition. If they had, they would have violated a request made several times by the first Algerian President Ahmed Ben Bella and his cabinet not to conduct atmospheric nuclear testing in their country – a call he notably extended to the rest of the world.

The publication in 2021 of Toxique, the French-language study of French nuclear testing in Polynesia by the physicist Sébastien Philippe and the investigative journalist Tomas Statius, recently highlighted the health and environmental risks taken for the sake of the French nuclear arsenal. Their analysis revealed much greater radioactive contamination in French Polynesia than Paris had admitted, with French forces conducting nearly two hundred nuclear explosions in the atmosphere and underground between 1966 and 1996.

Together with a round-table event including Polynesian civil society and French officials, the publication prompted French president Emmanuel Macron to order an unprecedented declassification of French nuclear archives. The importance of these documents for victims’ rights to compensation, which have been guaranteed by French law since 2010, raises questions about nuclear secrecy’s compatibility with democracy.

The recent study Des Bombes en Polynésie (2022), funded by Polynesia’s semi-autonomous government and edited by the French historians Renaud Meltz and Alexis Vrignon, has kept the public’s eyes on the Pacific. Most of the recent French declassifications also pertain to Polynesia.

Yet some of these documents create an opportunity to revisit Algeria’s nuclear history in the wake of the sixtieth anniversary of the country’s independence.

The Algerian Sahara, the first French test site

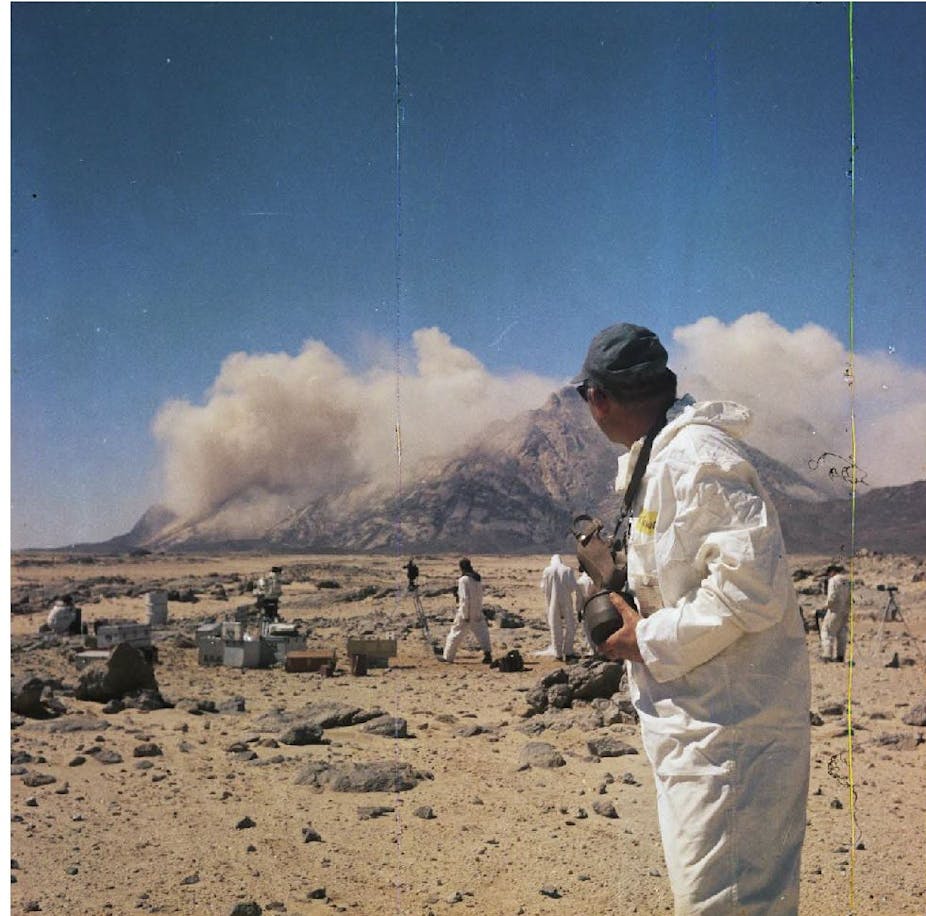

Between 1960 and 1966, France conducted in the Sahara Desert its first nuclear tests, totalling 17 detonations, including four in the atmosphere.

French nuclear ambitions collided with the Algerian War for Independence (1954–62), as the historian Roxanne Panchasi has explained, and then with the construction of the new Algerian state. Novelists, architects, and activists have also turned their attention to these French explosions in Algeria.

Four atmospheric tests took place near Reggane, an oasis town in the Algerian Sahara, before French underground tests began in 1961 beneath the Hoggar Massif. Underground testing, intended to prevent a radioactive leak produced by the nuclear explosion, did not always achieve this goal. Four underground explosions in the Algerian Sahara “were not totally contained or confined,” according to a French parliamentary report.

[Nearly 70 000 readers look to The Conversation France’s newsletter for expert insights into the world’s most pressing issues. Sign up now.]

The Evian Accords, which established the ceasefire in Algeria in 1962, granted France the rights to continue using both nuclear sites for five years. At least, that was the French interpretation, which several Algerian leaders would go on to contest. The agreement did not include any clause preventing the resumption of atmospheric tests on Algerian territory. But France did not resume atmospheric tests until 1966 in Polynesia.

Brought on by the Evian negotiations, the détente in Franco-Algerian relations allowed representatives of the new Algerian state to contest the most harmful of French nuclear plans.

Saharan fallout and African borders

The French decision in December 1961 to switch to underground tests would not last. Why worry about a return to atmospheric testing? Following the first French explosion in 1960 radioactive fallout had landed — much to the surprise of French officials and their allies — in independent Ghana led by Kwame Nkrumah’s pan-Africanist government and in Nigeria, a British colony also on the verge of independence.

The Ghanaian and Nigerian governments - as the historians Abena Dove Osseo-Asare and Christopher Hill have respectively documented - developed systems to measure French radioactivity in their countries. Other neighbouring states, like Tunisia, turned to the International Atomic Energy Agency, and eventually to the United States, for similar assistance with fallout monitoring.

Read more: The atomic history of Kiritimati – a tiny island where humanity realised its most lethal potential

These African officials wanted scientific proof that the French explosions in Algeria had violated their sovereignty. Controversy notwithstanding, top French officials, including de Gaulle, hoped to retain the possibility of conducting atmospheric tests in the desert near Reggane in Southern Algeria.

In late 1961, French military officials refused to alter air traffic controls above the site, explaining in one document that it was still “not possible to predict the characteristics of future tests that could be conducted at Reggane.”

In May 1963, the Algerian President Ben Bella grew impatient with the French refusal to cease nuclear activities in Algeria. French unwillingness to relinquish the test sites at that time threatened his domestic authority and his foreign policy, which both hinged on independence from Paris. He asked Jean de Broglie, France’s State Secretary for Algerian Affairs, if French forces could hasten their departure from Reggane since the site remained unused. De Broglie did not give a straight answer, claiming that “studies” needed to be carried out to determine whether an early departure was possible.

Ben Bella made the same request at least two more times in 1963 to the French Ambassador to Algeria Georges Gorse, who would confirm the French decision to keep the Reggane site several more years. French interest in retaining Reggane, and the possibility of resuming atmospheric tests there, seriously worried the Algerian president, who strongly supported the Partial Test Ban Treaty (1963). France did not sign this treaty, which outlawed nuclear explosions in the atmosphere, in outer space, and under water.

A fifth atmospheric test in Algeria? French plans to reactivate Reggane

Recently declassified French documents show that, notwithstanding Algerian protests, French officials likely prepared to conduct a fifth atmospheric test at Reggane in 1964. General Jean Thiry, in charge of the French nuclear test sites from 1963 to 1969, alluded in spring 1963 to “the reopening of the Hammoudia polygon [test site] for an atmospheric shot in 1964,” using another name for the blast zone next to Reggane.

Read more: Geometrically baffling ‘quasicrystals' found in the debris of the first-ever nuclear blast

Thiry and other top French brass worried about French capabilities to conduct underground tests following the infamous Béryl accident in 1962. Radioactive fallout from the poorly contained shot had contaminated the French state ministers Pierre Messmer and Gaston Palewski, French soldiers, and nearby Algerian communities.

Thiry was not the only French military officer to discuss new plans for Reggane. In March 1963, the Brigadier General Plenier, in the military engineering division, mentioned “the resumption of [radiation] protection experiments during an atmospheric shot planned for the beginning of 1964.” Even if he had faith in these plans moving forward, he noted that his work would “depend on details, not yet set, of the test conditions,” like the precise location or the altitude of the explosion. On March 29, 1963, the Division General Labouerie, also in military engineering, took his turn celebrating: “It could be possible that favourable conditions might come together for the atmospheric explosion planned for 1964.”

Back then, at least three military officers deep inside the French nuclear program eagerly expected the reactivation of the Reggane site. No atmospheric test took place in 1964, however. In the course of his meeting with de Gaulle at the Château de Champs near Paris in May 1964, the Algerian President Ben Bella had asked his French counterpart not to resume, if possible, atmospheric tests in Algeria. De Gaulle refused to guarantee it.

By the end of 1964, he was still discussing with his cabinet the possibility of conducting atmospheric explosions at Reggane, while they awaited the completion of France’s Pacific test site (le Centre d’Expérimentations du Pacifique) in Polynesia.

Even if French officials ultimately respected Ben Bella’s request, in December 1966 a top official at the French Atomic Energy Commission (CEA), Jean Viard, assessed the potential impacts of reactivating Reggane. Viard did not think the option was optimal. De Gaulle would have wanted to keep the site anyway. In a note to his cabinet in February 1967, he asked them to study how it might be possible to maintain a French presence at Reggane, a site that could, without substantial renovations, facilitate only atmospheric tests.

Nuclear archives and Algerian independence

Nothing guaranteed French abstention from atmospheric nuclear tests in independent Algeria. Recent declassifications have revealed French plans to resume these atmospheric tests, notwithstanding the protests from the highest levels of the new Algerian state.

Notwithstanding years of negotiations shrouded in secrecy, French authorities would fail to reach a decision about the use of the Reggane site before the Algerian authorities acquired it. Some French archives, including military and diplomatic files from this period, remain unavailable for historical research. But glimpses suggest the importance of this episode — involving French plans abandoned during bilateral negotiations — for the French nuclear weapons program, for the new Algerian state, and for the détente between these two countries. New access to French nuclear archives, despite gaps, has begun to illuminate little known aspects of Algerian Independence on its sixtieth anniversary.