France’s constitutional council has approved, with minor amendments, the “law consolidating respect for the principles of the Republic”, a bill that aims to counter “separatism” in French society. It is part of President Emmanuel Macron’s program to combat terrorism.

The bill includes measures to oblige neutrality in organisations that collaborate with public services, allow the government exert more control over charities and NGOs, require authorisation for home schooling and outlaw “virginity certificates”.

The law has been the subject of much controversy since it was drafted. Some on the left, including NGOs and university groups, say it is an attack on civil liberties, while others, including right-wing politicians, consider it too weak in its refusal to use the term “communitarianism” instead of “separatism” or to ban the veil in public spaces for minors.

Lire cet article en Français: “Lutte contre le séparatisme”, une loi qui stigmatise les minorités?

Separatism vs. universalism

In France, it is not forbidden to form a community – it is even part of the fundamental freedoms enshrined in the constitution, through the guarantee of freedom of association, worship, trade unionism and politics.

Sociologically speaking, forming a community means grouping together with others due to a feeling of belonging or shared common interests. It can be a good thing for society. But the term “separatism” in French has a purely negative meaning. Historically, the term “separatist” has been used to stigmatise attempts to organise religious, territorial or racial minorities in France.

This raises questions about the effects of this law on an already marginalised population, who are not mentioned in the text, but who are directly targeted by it: French Muslims.

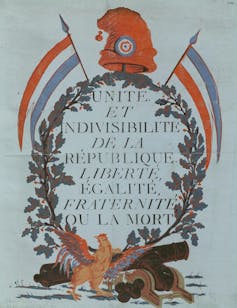

In France, the notion of separatism resonates because of its counterpart: universalism. The political theory of the French nation is based on republican universalism, i.e. on a nation understood as one and indivisible, with universal values, which apply to all its components, regardless of their origin, race, gender or social class.

In this context, the term “separatist” refers to communities that are supposedly hostile to the nation as a whole. The idea that some Muslims in France might place their faith and the norms of their religious community above their national belonging and the laws of the Republic would be characteristic of what is now often referred to as “Islamic separatism”.

A history of separatism

Muslims are not the first group of people on French territory to be suspected of separatism. Since the French Revolution, any attempt to promote the recognition of composite identities within the French nation (either religious, political or regional) been met with significant repression.

The term “separatism” was first used in 1939, according to criminal justice expert Vanessa Codaccioni. Back then, it targeted communists, suspected of promoting the interests of the USSR from within.

The notion has also been used to disqualify struggles against French colonialism, notably those of the Algerian people, and also autonomist movements within French territory, be they Basque, Guyanese or Martinican. It was above all President Charles De Gaulle who promoted the idea of the “separatist”, using it to attack his political opponents.

Accusing some Muslims today of being separatists is therefore part of France’s revolutionary and colonial heritage. It implies that a part of the national community behaves like an enemy within who would like to see territories (mainly the banlieues) and institutions (such as shools and hospitals) governed by the particular laws of a religious group, and not the universal laws of the national community.

Separatism or disadvantage?

According to an OECD study, it takes no less than six generations before an individual from the poorest categories can emerge from poverty in France.

Muslims, being predominantly members of these categories – both for historical reasons linked to colonial and migratory history and for sociological reasons linked to the discrimination they face – are directly affected by social and educational inequalities.

The law proposes greater scrutiny over families’ decision to home school their children. But initiatives to remove children from school among Muslim families could be attributed not so much to a desire to separate from the Republic for religious purpose, as to a desire to find an alternative to the endemic educational failures in working class neighbourhoods of France, as shown by the repeated conclusions of the National Council for the Evaluation of the School System.

Following the example of “ black condition ” described by French historian Pap Ndiaye, Muslim populations in France could be seen as sharing a “Muslim condition”. The concept of condition encompasses that of ethnic, cultural or social belonging without falling into the biological or homogenising aspects of the terms “community” or “race”.

In this case, “the Muslim condition” cannot be reduced to the sole question of religiosity, radical or not, but refers to a common social, economic or even spatial experience of a minority.

In other words, a person with an “Arab-Muslim” sounding name or one who comes from North Africa – thus racialised as “Arab” – will be assigned to the Muslim condition, whether they are religious or not.

Consequently, behaviour stigmatised as “separatist” could be understood not as a sign of religious radicalism, but as a strategy aimed at reducing the social inequalities suffered by people of this “Muslim condition”, the extent of which has only been highlighted by the pandemic.

How the bill could backfire

Adopting policies that restrict religious freedoms in this context are inappropriate and could even be counterproductive, by validating the radicalised narrative that France is “the enemy of Islam”.

The measures announced in the bill extending “neutrality” to people who work for private contractors of a public service reinforce existing infringements on the religious freedom of Muslim women who wear headscarves.

Meanwhile, the closure of mosques, which began in 2020 and will be easier to do under the new law, seem unfounded when we know that very few of the perpetrators of terrorist acts were radicalised in French mosques.

In targeting Islam in this way, the government risks creating religious deserts for Muslims by closing local places of worship in a religious landscape saturated by demand, thus undermining freedom of worship as guaranteed in Article 1 of the Law of 1905, also known as the principle of “laicité”, or secularism.

The law against separatism could thus weaken the Republican principles it claims to strengthen and further exclude an already marginalised population by denying its members any form of social visibility or the right to mobilise, either individually or as a collective.