Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains names of deceased people.

It would be interesting to learn who thought up this gimmick.

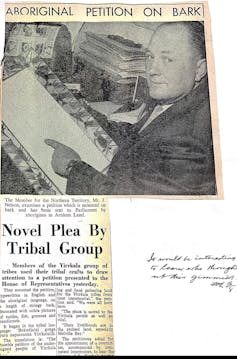

On August 16 1963, Cecil Lambert, the Secretary of the Commonwealth Department of Territories, scribbled these words next to a news clipping of a day-old article in the Canberra Times. “Aboriginal Petition on Bark” read the headline. “Novel Plea by Tribal Group”.

The article was accompanied by a black and white photograph of the then Labor Member for the Northern Territory, Jock Nelson, pointing at a white piece of paper framed by a painting representing Aboriginal motifs.

This petition, from the Yolŋu people of Yirrkala in North East Arnhem Land, sought consultation with traditional owners prior to the government granting mining leases in the region. It was presented by Nelson to the federal House of Representatives on August 14 1963 – 60 years ago this week.

Far from an eye-catching publicity stunt – an exotic sight bite – the representations of the various clans of North East Arnhem Land have gone on to produce an extraordinary legacy.

The Yirrkala Bark Petitions, as we now know these objects, have been called many things by many people over the past 60 years.

“The most famous petition ever put to an Australian parliament,” declared The Vancouver Sun on May 14 1971.

“Australia’s first native title deed,” stated political scientist Peter Botsman, simply enough.

The petitions were “rightly counted as among the founding documents of our nation”, vouchsafed then Prime Minister Julia Gillard in 2013, on their 50th anniversary.

Dr Yunupingu, who passed away earlier this year, was 15 in 1963. A student at the Yirrkala Methodist Mission school, he watched his father, Mungurruwuy, senior leader of the Gumatj people, orchestrate the unification of the 13 Yolngu estate groups of the Miwatj region (Gove Peninsula) to protest against the federal government’s excision of a portion of the Arnhem Land Reserve to pave the way for bauxite mining.

The Yolŋu people had not been informed of, negotiated with or compensated for the colonisation of lands they considered subject to their laws and sovereignty.

Yunupingu has been more circumspect than the politicians and pundits in his appraisal of the Bark Petitions’ democratic footprint. He called them: “a proud but sad symbol of my people’s fight for their land”.

How many were there?

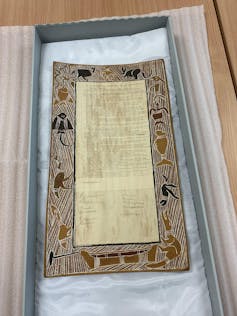

The two Bark Petitions that lie prostrate under glass in Parliament House were a grassroots community response to the clash of legal and land tenure systems on the 20th-century Australian frontier.

They consist of paper petitions, typed in both English and Yolŋu Matha and signed by nine Yolŋu men and three Yolŋu women, pasted in the centre of a bark frame.

This frame is painted with sacred clan symbols (land and sea creatures, plants, patterns and ancestral beings) that read together represent a claim to land ownership from time immemorial. Together, the painted designs represented a simplified version of Yolŋu title deeds, a window into the borders and boundaries of the Yolŋu national estate.

What the government did not see at this time – because it could not read the land and did not ask anyone for an interpretation – was that the Yolŋu had their own systems of governance, mapping, foreign diplomacy, border security, trade, negotiation and agreement-making, practised for centuries with other “outsiders”, particularly Macassan trepang fishermen from Suluwesi.

With this excision of land, Yolŋu law had been broken. The Bark Petitions were an attempt to respectfully communicate this breach in a language the Australian parliament could understand.

After Nelson presented the first petition, the Minister for Territories, Paul Hasluck, rejected it. He said the petition, having been signed by young people, including three women, couldn’t possibly signify the feelings of Yirrkala’s leaders, people of “status and standing”.

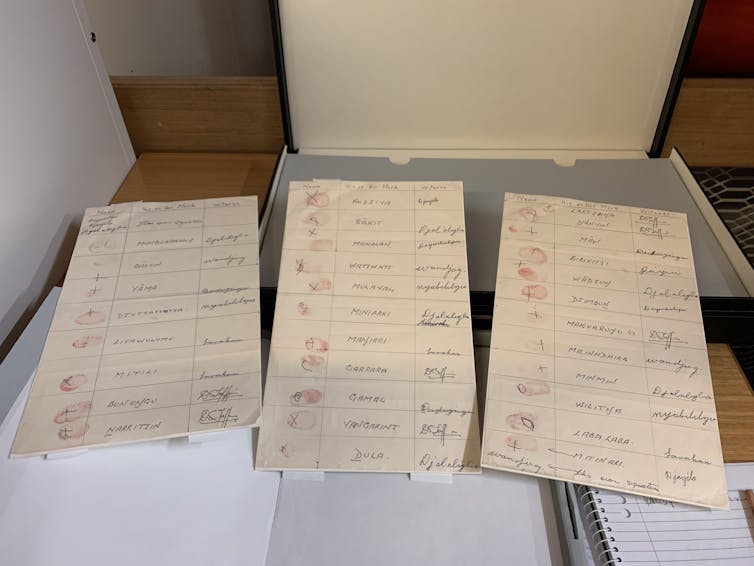

Furious that their views had been dismissed, 33 men and women of just such superior standing duly sent three pieces of paper to Canberra, signed with their inked thumbprints and witnessed by both senior Yolŋu and a missionary Doug Tuffin.

On August 28, the then Opposition Leader Arthur Calwell presented a second of the original Bark Petitions along with this thumb-printed imprimatur. A motion to implement one of the petition’s chief requests was successfully passed: to “appoint a Committee, accompanied by competent interpreters, to hear the views of the people of Yirrkala before permitting the excision of this land”.

The first formal petitions presented to parliament in an Australian language, they were the first to lead directly to a parliamentary enquiry. This bipartisan select committee took evidence from Yolŋu and European witnesses. It found in the Yirrkala people’s favour, recommending a standing committee be appointed to oversee development in the area over the next decade, with consultation – and compensation.

But this did not happen. So when the mining project began, complete with plans for a new mining town, the Yolŋu mounted the first land rights court case in Australian history: Milirrpum vs Nabalco.

Although the case failed – Justice Blackburn ruled in 1971 that British law had extinguished any native title rights – the action led to the Woodward Royal Commission, which paved the way for Gough Whitlam’s 1976 Aboriginal Land Rights Act NT.

So here we have a catalyst for Australia’s Indigenous civil rights movement, an avowedly significant turning point in race relations (created in the same year Martin Luther King gave his “I have a dream” speech). But what do we really know of the Bark Petitions’ creation? And their creators? We’re celebratory, but not conversant. We’re not even quite sure what to call them: are they artworks? Documents? Deeds?

Nor have we even been certain how many the Bark Petitions numbered. There were four, my research has confirmed.

I tracked down the fourth – “our lost treasure” as Yananymul Mununggurr, daughter of Dhunggala, the sole surviving signatory to the petitions calls it – to Derby, Western Australia, and facilitated a moving handback ceremony in November between the “missing” petition’s owner and a group of Yolŋu descendants of the original signatories and artists.

It is now being conserved in Adelaide and will soon be repatriated to Yirrkala.

A missing history

There are a lot of half-truths and a few out and out falsehoods lurking online. But there is no accurate, authoritative account of the events leading up to, culminating in, and flowing directly from the making of these hallowed objects, two of which lie – either mute or pulsating, depending on your ability to read them – in their current glass “shed” in Parliament House. A third is in storage at the National Museum of Australia.

What does a forensic scouring of the documentary archive – combined with direct consultation with eyewitnesses and descendants – have to tell us about the exact nature of the conflict that sparked these petitions?

As author Alexis Wright encourages us to ask of all stories: “What are the border lines? Where are the transgression points precisely?” In other words, what is the history of the petitions, a history that can and should be told – to use historian Henry Reynolds’ groundbreaking construction – from both sides of the frontier?

Given the acknowledged significance of the petitions as key documents in Australia’s past, it is remarkable no such history exists. This absence is even more astounding given that North East Arnhem Land has, since at least the 1930s and especially since the 1960s, been the fertile research playground of anthropologists, linguists, musicologists, educationalists, art critics, curators, activists, filmmakers and legal scholars. Historians have been in short supply.

The Bark Petitions are routinely wheeled out as a crucial, if hazy, reference point for the cascade of civil and land rights-related events that followed: Wave Hill and the Gurindji, the 1967 Constitutional Referendum, the Gove Land Rights Case, the Tent Embassy, the Northern Territory Land Rights Act, then a hop, skip and a high degree of difficulty jump to Mabo, where the weight of scholarship lands.

Read more: Friday essay: the untold story behind the 1966 Wave Hill Walk-Off

But despite this legacy, anecdotal evidence I’ve gleaned over a ten-year research journey suggests the vast majority of Australians have never heard of the Yirrkala Bark Petitions, let alone understand any of the finer points of their political significance. Those who have viewed them in Parliament House often remember them in ethnographic terms: striking traditional artworks rather than innovative, discursive records of legal intent and political will.

And not even that aesthetically arresting to some, perhaps. In 2015, the then treasurer Joe Hockey, while attending the Istanbul Biennale, asked Australia’s Ambassador to Turkey, James Larson, what the object behind glass in a display case was. Larson apprised him that it was one of the original Yirrkala Bark Petitions, brought to Turkey along with a few other items of Yolŋu/settler significance by Biennale Director Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev. Although Hockey had presumably walked past this petition hundreds of times in Parliament House, he claimed to have never heard of them and “express(ed) surprise that he had to come to Turkey to learn about it”.

This ignorance says much about our national pastime of historical amnesia, our wilful forgetfulness of any event that falls outside the canon of military achievement – or failure.

It is precisely why the Uluru Statement from the Heart includes a truth-telling component in its invitation to all Australians to engage in a process of constitutional recognition and historical reckoning. Our unfamiliarity with the Bark Petitions also reflects poorly on Australian civics education. (Hands up who has heard of the US Declaration of Independence.) Ultimately, the gaps in our collective colonial knowledge point to a lazy relationship with our own democracy.

This absence sells us short as a nation, for the Bark Petitions represent more than simply a pivotal step on the path towards the legal recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander land and sea rights.

My research into how the petitions came into being, and what they meant to the community that crafted them, makes a larger claim for the significance of both the artefacts and the processes that led to their creation.

The petitions constitute nothing less than the third pillar of a trinity of material objects that, read together along a historical, political and cultural continuum, comprise our founding documents: the material heritage of Australian democracy.

Flag. Banner. Bark.

As the US has its Constitution, Bill of Rights and Declaration of Independence, so Australia has a triad of nation-defining archival “documents”. Ours are arguably more inclusive, not being written on paper by a literate elite, but rather handmade by “the people” for the purpose of proclaiming their right to be counted.

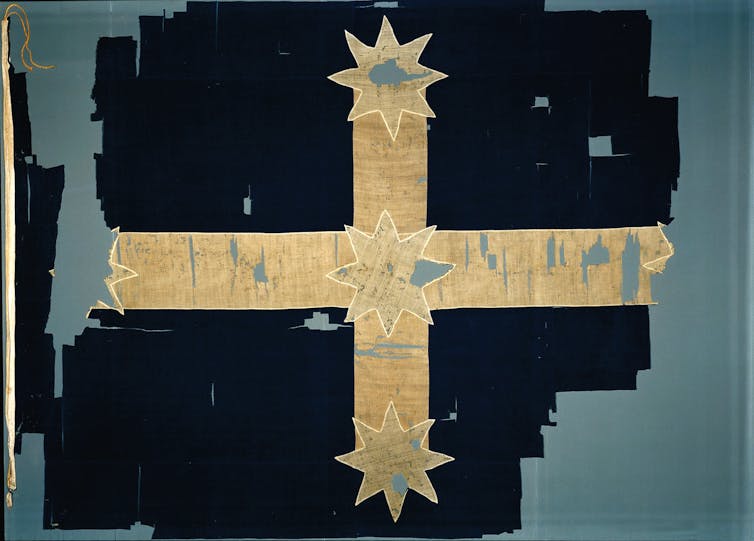

Exhibit A: The Eureka Flag. Symbol of the struggle for rights and liberties by a disenfranchised cohort of newcomers to gold rush Victoria, men and women who fought to have the voices of unpropertied people heard in making the laws that governed their lives, including the right to representation for their taxation. In 1854, they sewed a flag that represented the collective identity and aspirations of the polyglot miners and merchants who rallied beneath it.

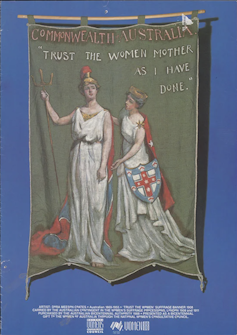

Exhibit B: The Women’s Suffrage Banner, painted by Dora Meeson Coates. With the passage of the Franchise Act in 1902, Australian women became the most fully enfranchised in the world. They heralded their peerless political equality on the world stage with a magnificent banner. “Trust the women, Mother, as I have done,” the precocious daughter Australia goads Mother England in bright red lettering atop the banner, which was paraded before hundreds of thousands of people in London’s mass Suffragette street rallies of 1908 and 1911.

White women, that is. For the Franchise Act of 1902 threw all Aboriginal Australians under the bus – preventing them from voting in federal elections. The Immigration Restriction Act passed by that inaugural post-federation parliament similarly ensured that the latest immigrant was only the youngest Australian if he or she was European and white.

It would take another 60 years for the Yolŋu people to throw the bus out with the democratic bathwater, not only a display of remarkable colonial literacy but also a feat of diplomatic ingenuity.

Flag. Banner. Bark.

All three, conceived and crafted not by the minds and hands of statesman, lawyers or archetypal founding fathers, but by men and women on the ground, embedded in the struggle, fighting for rights and recognition, dignity and decency, demanding their voices be heard and their sovereign bodies be counted, holding lawmakers accountable to the notion that government by the people and for the people should mean all of the people.

Flag. Banner. Bark.

Each of these declamatory objects speaks back to power, a creative act of resistance to a perceived political injustice. Like the stories of the creation, presentation and reception of the Eureka Flag and the women’s suffrage petition, the story of the Bark Petitions takes us to a time when democratic inclusion, when basic entitlements of citizenship, could not be taken for granted by certain sections of the body politic.

While the Bark Petitions were sent to, and continue to reside in, an institution devoted to democratic governance, their story of their creation also contributes towards what academic and writer Marcia Langton has called “the story of the Aboriginal part in Australia’s economic history”.

Proposing in her 2012 Boyer Lectures that the mining boom then gripping the nation was affording economic opportunities for Aboriginal entrepreneurs and workers, Langton argued that “we need to understand the forces at work, historical and economic, that have produced the present situation”. Whereas in the 1960s, northern Australia was the new frontier of such opportunism – or exploitation – by the first decades of the 21st century, Langton proposed such remote regions as “the geographical heart of this activity”.

The story of the Bark Petitions also shifts historical timelines, pointing us to a version of Australian Indigenous democracy whose political and philosophical traditions go back much (much) further than John Stuart Mill or the French Revolution or even Ancient Greece.

Might the deep time heritage of Yolŋu laws of governance not only challenge the contours of the standard nationalist narrative of progress, but set fire to the map altogether? Were Australia’s First Nations people also the nation’s first democrats?

Negotiation

We must always begin with negotiation. It’s the start of the journey. It’s the dot where you start and you need to join the dots …

These are the words of the Gay'wu Group of Women, a collective of Yolŋu sisters and Ngapaki (white) researchers from Macquarie University. This collaboration of traditional knowledge-keeping and on-country learning produced the extraordinary book, Songspirals, which won a 2020 Prime Minister’s Literary Award.

In life and death, we always negotiate through bala ga’ lili, through give and take … give and take sustains all existence, the existence of the clans, of lands, of knowledge and of relationships with others, including ŋäpaki.

There is always a process, a way of going through the right process of negotiation. This is negotiating and renegotiating relationships between clans and their responsibilities.

The Yirrkala Bark Petitions were a manifestation of these governance principles. Elders and clan leaders, who could not write, selected young, literate members of the community to represent the estate groups’ collective interests. This selection process upheld principles of Yolŋu rom (law).

Their “petition” was not so much an entreaty as a form of treaty between two sovereign nations: the Commonwealth of Australia, which had only enfranchised its First Nations people a year earlier, in 1962, and the united clan estates of the Miwatj region of North East Arnhem Land, people who had been negotiating agreements and conducting international diplomatic relations with other seafaring groups for centuries.

In sending the Bark Petitions to Canberra, the Yolŋu people offered the gift of their own knowledge and representation of land boundaries and ownership principles. They combined this law and cosmology (the bark painting) with the form of representation required of the Australian Parliament (written words set out in the format required of Westminster humility – “your petitioners humbly pray”).

Cross-cultural activism

The Bark Petitions constitute a genuine exercise in shoulder-to-shoulder, crosscultural political activism and dissent. The idea for them was, in fact, conceived by Labor MP Kim Beazley Snr, while standing in front of the recently installed bark art panels in the church of the Methodist Overseas Mission, established in Yirrkala in 1935.

The panels were commissioned by the Mission’s new Superintendent, Reverend Edgar Wells, in an act of remarkable religious syncretism. (Will Stubbs, convenor of the Buku Larnngay Arts Centre in Yirrkala, where the Church Panels are now displayed in a purpose-built, cyclone-proof chamber, has called the artworks the Yolŋu world’s Sistine Chapel.)

The petitions were first drafted in English (likely with significant input from Wells), incorporating the requisite parliamentary language provided by Beazley, and translated into Yolŋu Matha by Djapu ngalapal (leader) and teaching assistant Daymbalipu Mununggurr and Margaret Croxford, the school principal’s wife. Twelve copies of the petition, in both languages, were typed up by Ann Wells, the Superintendent’s wife.

The paper copies were then signed by 12 community members representing six clan estates. The signatories were carefully selected by elders from the clans. Four bark frames were painted in a frantic overnight session by four selected artists, as a form of “mapping” of the clans’ collective land holdings. (The remaining paper copies were sent to other federal and Northern Territory MPs. Several of them are held in the Parliament House archives, and I found one of them tucked away in Robert Menzies’ papers at the National Archives, in a file unopened since 1963.)

They were then parcelled up by Ann Wells and sent on the mail plane to four politicians: Prime Minister Menzies, Calwell, Beazley, and Labor MP Gordon Bryant, President of the Federal Council for Aboriginal Advancement. (It was Menzies’ petition that Nelson presented on August 14.) A truly disruptive act of political syncretism.

As Edgar Wells noted, “the Aboriginal people had established a direct line of communication with the Australian Parliament”.

Though the Aboriginal people of the Northern Territory were legally classified as “wards” at the time (and officially referred to as “natives”) they acted like citizens, “by-passing”, as Wells argued, “all previous lines of authority”.

Explaining his intervention on the Yolŋu’s behalf to Beazley, Wells said:

my simple reason for all this is that the aboriginal is a person – not a number, and the first time he has used the very instrument we encouraged him to cultivate, namely political awareness, the Government cannot stand it.

‘The tongue of the land’

Djambawa Marawili AM is an award-winning artist and senior leader of the Madarrpa clan of North East Arnhem Land. Djambawa played an instrumental role in mobilising the Sea Rights claim that resulted in the 2008 High Court decision granting traditional owners exclusive native title rights to the land between the high and low water mark of the Blue Mud Bay region.

He was ten when his family members helped create the Bark Petitions and decades later, spoke at that Istanbul Biennale. Djambawa explains the indivisibility of art and identity, land and law, politics and personhood, culture and cosmology like this:

The land has everything it needs.

But it couldn’t speak. It couldn’t express itself. Tell its identity. And so it grew a tongue.

That is the Yolngu. That is me. We are the tongue of the land.

Grown by the land so it can sing who it is.

We exist so we can paint the land.

There is a new document that flickers from the incendiary embers of the Yirrkala Bark Petitions: the Uluru Statement from the Heart. This document is not a petition so much as an invitation. (Though the Bark Petitions were enticements to healing and mutual understanding too – not a gimmick but a gift to the Australian nation — as all lasting acts of cultural and political diplomacy must be.)

Like the petitions, which set out the contours of Yolŋu land ownership, so the the Uluru Statement provides a map too: Voice, Treaty, Truth. Signposts to a new dawn for an old country, an awakening based on consultation, recognition and restorative justice.

The Uluru Statement calls for the Australian Constitution to grow a tongue. It is time for us to listen.

This essay is edited and adapted from the author’s forthcoming book on the history of the Yirrkala Bark Petitions, the third instalment of her Democracy Trilogy, to be published in 2024 by Text.