What does a writer’s education look like? Is it access to books, regular letter-writing, difficulty in childhood (war, illness, a brutal boarding school)? What talent or disposition primes the young writer for their training? In the push and pull of nature versus nurture, a key element is the right teacher, at the right time: the encouraging, goading or resistant pressure that nudges along the curious mind.

The essays in a new book edited by Dale Salwak, Writers and their Teachers, lead you to reflect on your own teachers, but one of the themes is that the writing teacher, in retrospect, takes many forms.

I recall Mrs Wagstaff, a dinner lady at my English primary school with dyed red curls and long fingernails, who occasionally read us stories on rainy lunchtimes. “See it in your mind’s eye,” she said to us, as we sat cross-legged on the carpet, 40-odd years ago. I did see it in my mind’s eye, and still do.

We all pick over stories of personal transformation in adulthood, the scenes and dramatis personae vivid across the years. Who was it who made the difference, and how? Writers and their Teachers reads as a collective bildungsroman, in which we come to understand the forces that shaped the adult writer. In this genre, the teacher or mentor is central, guiding the apprentice towards mastery.

Such transformations call for belief on the part of the teacher, and a spark of interest in the student. Salwak, in his introduction, quotes Ralph Waldo Emerson:

The whole secret of the teacher’s force lies in the conviction that men [and women] are convertible, and they are.

Here we witness 20 such conversions, from a young person with a desire, or perhaps only its flicker, to a life ablaze with language, ideas, images and story.

Unlikely teachers

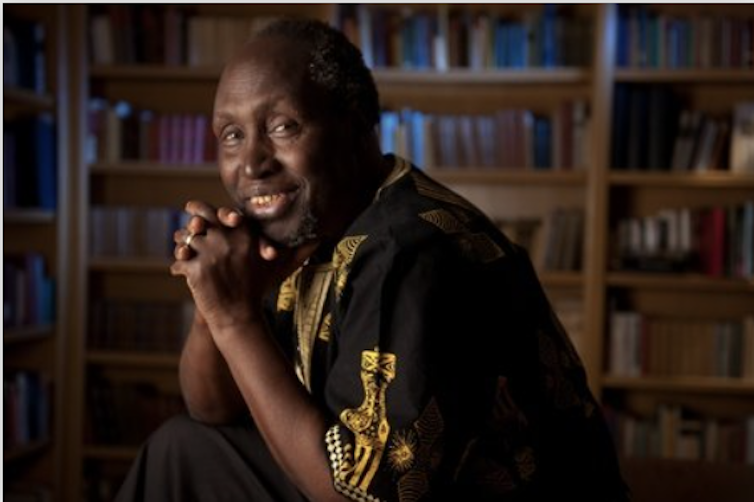

Kenyan literary giant Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o names his illiterate maternal grandfather as his first writing teacher.

Ngũgĩ became his child scribe, reading aloud his grandfather’s letters until they represented perfectly what he wanted to say. This process not only taught him “the value of the written word and the revision necessary to make it read smoothly”, but crucially “the beauty of written Gĩkũyũ”, his mother tongue.

Ngũgĩ thrived at school, speaking, reading and writing in his first language, but in 1952, the colonial government banned African-run schools, and use of local languages became dangerous.

Ngũgĩ’s first books, including his classic of the Mau Mau rebellion, A Grain of Wheat, were written in English, the language of the coloniser. In 1977, Ngũgĩ helped to write and stage a politically outspoken play with Gĩkũyũ speakers.

Imprisoned for over a year as a result, and surrounded by Gĩkũyũ “teachers” in the form of his guards, he wrote his first novel Devil on the Cross (on toilet paper) in his first language. Ngũgĩ writes:

So, it was a maximum security prison in Kenya which made me return to my roots, under the literary tutelage of my grandfather, Ngũgĩ wa Gĩkonyo, to whom I am eternally grateful. He was indeed my first literary teacher.

Few lessons in these essays are learned at such great personal risk, but many of the writers also credit unlikely teachers. The British detective novelist Catherine Aird moved as a child to a village in which she knew no one, and was struck down by that not unusual formative event in the biographies of writers, a long childhood illness. She worked her way through the contents of the village library, plunging into the Golden Age of detective fiction. Her family was also training her to appreciate a puzzle:

I lived in a household daily engaged in solving crosswords and with a keen (and wily) bridge player for a mother and a medical father who likened diagnosis to simple detection.

Aird paints a cosily macabre picture of the breakfast table, with her doctor father sharing his enthusiasm for forensics, recounting a gruesome local murder-suicide case in which he was advising the coroner. She even played assistant to his detective work, on one occasion sent upstairs in a house in which a man was

found unconscious at the foot of his stairs to feel whether the bed was still warm and thus help establish when he had fallen.

Sometimes what the young writer needs to learn is how to navigate the wider world glimpsed through reading and writing. Michael Scammell, biographer of Solzhenitsyn and Koestler, spent two years as a copy boy at the Southern Daily Echo in Southampton, the first in his family to be educated to 16.

A grammar school boy in the English selective system, he had left his own world behind without a guide for the journey. The older journalist Anthony Brode, “giant of the newsroom”, a bohemian francophone, relaxed, cultured, product of a privileged education “taught me how to write – and live – in an unfamiliar environment”.

A book about education (particularly when the writer is British) is also a picture of class and a navigation of its boundaries. Tony’s home was a revelation:

Unlike my family’s small living room, where four of us huddled over a coal fire on wintry nights with the radio blasting, making it hard to read, Tony and Sylvia’s comfortable lounge was spacious and warm, and I had free run of their bookcases (there was no television, of course).

In these shelves, Scammell discovered the fiction of Orwell, Wodehouse, Hemingway and Fitzgerald. Books, of course, are our other teachers. Later, Tony provided the connection via his publisher for Scammell to begin publishing translations, and he was on his way.

The friendships that emerge from such unequal beginnings are often long and distinguished by the generosity of the mentor. A gentle awe infuses several of the essays, that so much can be given with nothing asked for in return. As poet-critic William Logan writes on his unconventional professor David Milch (creator of NYPD Blue and Deadwood):

there are debts that cannot be repaid because you do not possess the currency in which they were tendered.

Sir Vidia’s gifts

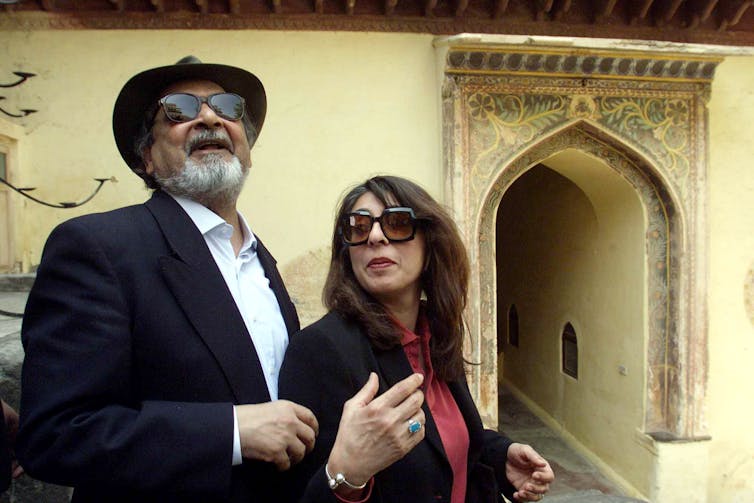

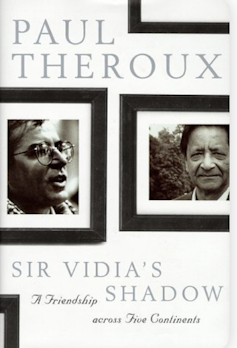

The gift bestowed by V.S. Naipaul, Nobel laureate, on the younger writer Paul Theroux, was great, but ambiguous. Theroux writes:

More than fifty years of writing about Naipaul and reflecting on his influence! Yet it is only in the last few years, the dust having settled, that I have re-examined our relationship and seen how complex it was, how important – how crucial – it was to my becoming a writer.

This is the final essay of the collection. Arranged as the pieces are in a journey through “School”, “College” and “Graduate School and after”, a growing sense becomes evident, as the writers recall themselves as adult mentees rather than as children, of their teachers as flawed human beings. This is perhaps difficult to avoid in Naipaul’s case, but for Theroux, Naipaul’s snobberies and imperiousness – and a 15-year break in their friendship – do nothing to undermine his significance.

When Theroux met Naipaul in Kampala in 1966, he knew no novelists and sought guidance. As Naipaul’s driver, escort and interpreter, he was able to observe at close quarters his utter seriousness about writing, and to receive its lessons in a terror-induced atmosphere of total concentration.

Mine was an animal alertness: no creature is more wired than an animal in unfamiliar surroundings – every faculty is twitchingly alight, every synapse engaged. I was fully awake in his presence and fearful of making a blunder.

When this 30-year apprenticeship ended in rejection born of one of Vidia’s “foul moods”, Theroux saw it as liberation: “promotion to a higher rank”. He was now free to write his controversial memoir of their friendship, Sir Vidia’s Shadow. In the end, Theroux has no regrets. What “every aspiring person” needs, he tells us, is encouragement and belief. “Naipaul did that for me: he alone told me what I was capable of doing.”

House calls

The form the mentor most usually takes in these pages is the school or university teacher, and it is often in the glimpse of them as something more than a teacher that they take shape.

J.M. Coetzee recalls Gerrit Gouws, a cane-bearing disciplinarian who taught the final stage of Worcester Boys’ Primary. One day Mr Gouws broke role to invite the young John to tea, who was amazed to learn that his teacher lived on the same housing estate as he did.

As far as I was concerned, outside the classroom [teachers] might as well have had no lives.

Here and in other essays a teacher opens up the mysteries and possibilities of other people by revealing an existence beyond the borders of school. Historian and biographer Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina writes of her kind and imaginative teacher Mabel Morrill:

we had no notion that she could even have a personal life that would interest us.

Like Coetzee’s Mr Gouws, Mrs Morrill stepped out of the classroom and into her pupil’s life, calling at her house. She had noticed that Gretchen made her own clothes (the teacher taking the trouble to notice is a potent force in this book), and asked to be measured up for a dress, setting off a chain of connections which brought Mrs Morrill vividly into three dimensions.

When the young Coetzee visited his teacher for tea, he made his own discoveries, most improbably, that Mr Gouws had, “of all things,” a wife. What could all this be about? he wondered at the time, but sees now what such a moment always tends to mean: that the teacher views the pupil as an individual, worthy of interest, deserving of encouragement.

The memory also allows Coetzee to access, 70 years on, the significance of his being taught in English, and paid a small extra attention, by an Afrikaner. This teacher, across a social and cultural divide, taught students with more natural facility than himself “the ability to take sentences of the English language to pieces and put the pieces together again”.

Mr Gouws would have operated according to the teacherly hope that some of the children you meet in your years in the classroom will make the fullest use of what is offered. How well this gamble paid off in the case of the future Nobel prize winner who came to tea.

Learning to read

The exhilaration offered up by paying meticulously close attention to language is one of the gifts enumerated in Writers and their Teachers. Former British Poet Laureate Andrew Motion learned close reading from his poet-teacher Mr Way, who had been immersed in New Criticism at Oxford. This mainstay of mid-century literary studies, as Motion writes:

concentrated rigorously on the text and paid little or no attention to biographical facts or historical context.

Motion grew in time to appreciate the connections between the poem and its world, but like many other writers who passed through an education system in thrall to this rigorous separation, the experience of encountering poetry in a “pure form” remained a foundational lesson.

Mr Way and his methods arrived in Motion’s life as balm after the brutalities of an English prep school. The pupil learned in his classes that the distilled nature of poetic language demands a focus approaching that which produced the work.

This discovery was joined by another: that language relies for meaning on sound as well as sense. Poetry became

a forest of cadences and associations in which no interpretation can be “wrong” […] provided I’m able to explain and justify it.

The drama of education is that its transformations occur amid the difficulties of childhood and young adulthood. In this context, knowledge can feel like rescue.

Words that change everything

Biographer Carl Rollyson structures his essay around the life-changing comments his teachers made. Like others here, he suffered great difficulty in his young life, in this instance the loss of his father to cancer.

His chapter begins with the words of his English teacher James Allen Jones: “You read beautifully,” after he had recited a speech by Cassius in Julius Caesar.

He put his hand on my arm when he said the words, and it was as if I had been reborn. Some teachers have that power: to move you with a voice that liberates you to be yourself.

This liberating power is the true subject of this book. Again and again, we see the teacher lay out the tightrope and hold it taut, as the young writer clenches their toes and steps out above the air.

I paused reading to write to an old school friend about our English teachers at secondary school. When we were 16, our beloved English teacher Miss Quinn, wearer of bright silk suits tailored on her annual trips to Thailand, was replaced by a new teacher who was more austere, less of a friend to us. She had been a missionary, and seemed otherworldly, but it was she who wrote on a piece I wrote about early childhood, “You are a real writer.”

What do you do with that? Remember it in moments of uncertainty, and try to honour it.

Full circle

Students who liked learning often become teachers themselves. Novelist and poet Jay Parini recalls his college advisor Ed Brown, how impressed he was by him, how he came to imitate his clothes and manner. Even now, when he walks into a classroom, he thinks: “I’m Ed Brown today, reborn.”

The novelist Margaret Drabble, a graduate of Newnham College at Cambridge, found herself teaching in a very different institution, Morley College in Lambeth, established for the purposes of educating the working classes in a slum area. By 1969, when Drabble arrived, her classes were filled with young mothers, taking advantage of the creche facility and flexibility of curriculum:

the majority of the group were young women like me, and together we explored the world of literature, making up our own syllabus and our own lives as we went along. I was my own student. We taught ourselves.

These women of the 1970s were living out change, and Drabble was learning and teaching at the same time, as is the way of things. At the end of her essay, Drabble states simply: “We learn much from those we teach.”

The step into teaching is an important developmental stage in many writers’ journeys, as well, perhaps, as a partial repayment of one’s debt.

How in the end are writers made? The answers in this book are – to a degree – specific to certain contexts. For example, only four of the writers are women. As well, contributors tend to be of a certain age. If younger writers were asked about their education, perhaps we would see some essays on the teaching and mentorship taking place in writing centres and community organisations, that can lead to the airing of new voices.

Still, the deep experience of the contributors offers a long view, and makes for rich storytelling, textured by living histories of education, class and literature. What we learn is that it is a dual gift their guides bestow: demonstrating what is possible, offering the courage to reach for it.

Work to do, but worth doing

I recognise some of the paths these writers have walked, and yet there is no map to the writing life. Who were my teachers? At first, before school, someone taught me to read. Was it my parents? My recollection is that I taught myself, but no doubt there was more to it.

At school I was allowed to read ahead, wandering through the corridors in the quiet of lesson time – free and trusted – to access shelves outside the other classrooms.

In third year, lovely Mrs Rudra, who allowed the girls to wear her saris as a treat (how cool the silk felt on my skin), organised for me to exchange letters with a children’s author, Rosemary Manning. I had a terrifying teacher in fifth year but she had no problem with my nerdy habit of putting on plays for the other children.

My grandmother, throughout my childhood, insisted I was going to be a writer. This was my education. Strong nudges, provision of resources, a long leash.

At the end of secondary school I encountered close reading in the form of the Practical Criticism exam (here is a poem: knowing nothing of its contexts, analyse it), but also in the forensic discussion of a single, two-word line – “Kill Claudio” – from Much Ado About Nothing. Our English group of five, plus Miss Yates, planting careful provocations, spent a whole class arguing delightedly about it.

Later, at Nottingham University, I stood marvelling with my friends outside the military-looking huts of the American Studies department, having spent an hour picking through William Stafford’s poem Traveling through the Dark with our lecturer, the gentle, patient, unpretentious Dave Murray, feeling the same exhilaration as after the Kill Claudio class. So few words, so much meaning, if someone showed you how to pay a special kind of attention.

I spent a summer on exchange in the States. At American universities, unlike in England, you could take creative writing classes. My teacher was the poet Susan Firer, who modelled the life of a person who lived in writing.

She told us about waking early to write and walk, about going to see other writers read when she was young. She was serious and kind, and left “nice"s dotted through my journal: small, sweet gifts. The desire to write was latent before this, a flicker; explicit from then on.

Much later, I studied for a creative doctorate in Sydney, writing a novel, a fictionalised account of the lives of my grandparents, for my thesis. I submitted a section for workshopping. "Your grandmother is important to you,” the workshop leader said, “but why is she interesting to us?”

A fair question, which I found devastating, until I had tea with my supervisor, the novelist Gail Jones, to discuss the work in question. She paid this far from finished work a patient, brilliantly focused attention that was instantly cheering. “There is work to do,” I felt her saying to me, “but it is worth doing, and you are the person to do it.”

I teach writing now at university. You see a glint in students, as they transform uncertainly into whoever it is they are becoming. Some way into semester, one of them will peel off from the crowd to ask you about a future in writing. You have to tell them there is no money. You have to say there is no path.

You hope what you are also saying, in this moment, and when you stand in front of the class, week after week, talking about their writing and other people’s, is that it is worth it. If you love what words can do, why wouldn’t you want to live a life shaped by their potential?