Pride and Prejudice (1813) is by far Jane Austen’s most popular novel but, for literary critics, Emma (1816) is more often ranked as her greatest achievement. Or – in an era in which phrases such as “great books,” like “great men,” are apt to make the most hardened aesthete blush – her most intelligent.

Yet, at the time of publication, Emma’s longevity was far from guaranteed – reviews were few and far between, sales figures were less than promising, and the novel’s young and artistically obscure author soon fell into a mysterious decline, dying of an unnamed illness eighteen months later.

So how did this, Austen’s fifth novel, make the epic 200-year journey from the dusty bin-ends of John Murray’s publishing house to endow its author with the mantle of extraordinary and apparently inexhaustible celebrity?

Emma tells the story of the novel’s eponymous heroine, a young and slightly conceited resident of the English village of Highbury of whom Austen famously wrote “no one but myself will much like”. Emma is desperately immature, frequently misguided, and meddles in the lives of the characters around her, often to terrible effect.

Though Emma is more affluent than most Austen heroines, being “handsome, clever and rich”, like all Austen novels the book explores the economic precariousness of women’s lives in the early 19th century – its plot turns on questions about whether the characters should marry for love, necessity, practicality, or indeed, money.

The 21st century has seen what might be called the Harlequin-isation of Austen – the reinvention of Austen as the queen of the rom-com – but Austen is in fact an uncompromising if cheerfully ironic moralist. It is Austen’s peculiar brand of acid-bath realism, and her eye for the minutiae of social and class hypocrisy, which constantly catches the attention of critics.

Emma is also the novel in which the inimitable Jane Austen persona appears at its most arch, and pyrotechnically accomplished. It is justifiably celebrated as the text in which a new kind of writing called “free, indirect discourse” is virtually invented, although this style of writing can also be glimpsed in the earlier works of authors such as Goethe.

In this kind of novelistic narration the voice of the author and her characters appear entwined – that is, the elements of authorial narration and internal monologue are mixed – giving rise to a new use of language that paved the way for modern writers to paint their compelling images of human consciousness.

Literary realism

Emma drew unmitigated praise from Sir Walter Scott, who, in 1816, saw it as the harbinger of a new kind of literary realism:

We, therefore, bestow no mean compliment upon the author of Emma, when we say that, keeping close to common incidents, and to such characters as occupy the ordinary walks of life, she has produced sketches of such spirit and originality, that we never miss the excitation which depends upon a narrative of uncommon events …

“In this class,” Scott added, “she stands almost alone.”

But it was not until the publication of George Lewes’ 1852 essay The Lady Novelists that Austen was marked as an author not to be neglected. Lewes singled out Emma, alongside Mansfield Park (1814), as the pivotal work that consolidates Austen’s position as a “writer’s writer” – that is, a writer who, though not yet widely read, was nonetheless appreciated by those “cultivated minds” best placed to “fairly appreciate the exquisite art of Miss Austen”.

Lewes’ review also signalled the themes of gender and class that were to enthral Austen fans and critics for the next 200 years. He sketched in Austen’s signature “womanliness”, but without a “woman’s mission” (in more contemporary terms, without the ideologies of a blue-stocking feminist), her single class perspective as a “gentlewoman”, which he significantly qualified with the phrase “English gentlewoman” – betokening the critique of Englishness that has been a regular feature of Austen scholarship since Edward Said first analysed Mansfield Park as the exemplary novel of British “unconsciousness” about Empire.

Lewes’ essay is a signal contribution to what might be called an extraordinary history of reading Emma. He wrote just before the popularity of Austen took off, rising incrementally to the astonishing peak of what is sometimes called Austen-mania today.

He readily acknowledged that Maria Edgeworth was far more widely read. But he also pointed forwards – in an almost uncanny way – to a future moment in history when “Miss Austen, indeed, has taken her revenge with posterity”.

Reading Emma

Emma was published late in 1815, though the date on the first edition appears as 1816. John Murray ordered 2,000 copies and sold them at 21 shillings for a three-volume set. Austen made about £221. Maria Edgeworth earned twice as much for a book published in the same period. In 1821, 539 copies of Emma were remaindered at 2 shillings each.

Although Emma was temporarily shelved in England, on the strength of Scott’s review Matthew Carey published it almost immediately in Philadelphia.

Unlike all the other Austen novels published by Carey in the ensuing decades, under the imprint of Carey and Lea, Emma was the only text to escape the watchful eye of the East Coast censors.

In American editions of Austen’s other novels, expressions of extreme distress, surprise, or thankfulness – “Oh God!”, “Good God”, “Thank God”, and even “by G––”, were vigorously expunged to protect religious sensibilities. Not even Tom Bertram’s “By Jove” – uttered in Mansfield Park – escaped excision.

In Emma, as Austen scholar David Gilson painstakingly established long before the invention of digital word-searching, God is invoked on at least eight occasions, the Heavens is invoked on four, and even Emma sinks so low as to exclaim, “Lord bless me!”.

But in deference to Emma’s status as a model of English decorum – perhaps – these exclamations miraculously escaped the gaze of the Philadelphia puritans, both on the book’s initial and subsequent printings.

Also in 1816, mere months after its initial release, a French translation – La Nouvelle Emma – appeared in Paris. The long introductory essay gives clues to the kinds of readers the publisher expected.

It comments, for example, on the virtues and attributes of the true English “gentleman”, and concludes with the advice that the novel contains suitable subject matter for women, asserting that,

mothers can give it to their daughters.

It was the 1833 reprinting of Emma as part of Richard Bentley’s Standard Novels series that first brought the book to the attention of a wider reading public. Bound in dark cloth, all the Bentley novels carried an engraved frontispiece featuring a scene from the book in question, with a matching vignette on the title page, and were sold at a price that made them affordable for a middle-class audience.

The frontispiece of Bentley’s edition of Emma depicts Mr Elton gazing rapturously at Harriet across the drawing room, but with his hand meaningfully placed upon Emma’s sketch of her. The caption underneath artfully draws attention to the ironic perspective generated by Austen’s characteristic use of free, indirect discourse:

There was no being displeased with such an encourager for his admiration made him discover a likeness before it was possible.

It is of course Emma – and perhaps her fortune – that is the real object of Mr Elton’s attention.

Bentley’s editions, engraved by William Greatbatch from drawings by George Pickering, inaugurated a 19th-century tradition of Austen illustration. The theatrical poses, the aesthetic correspondence to commercial fashion plates, blend together with what might even be called an emerging tradition of adapting and updating the story.

It is striking that the characters’ clothes are more reminiscent of the fashions of the 1830s than the Empire lines of Austen’s own day.

Once the copyright on Emma expired in 1857, there were more editions and, by 1880, Emma was continuously in print. There were famous editions by George Dent and Macmillan, and an edition by Simms and M’Intyre that changed the line “sign of sentiment” (chapter 32) into the more Victorian “sigh of sentiment”, according to Gilson.

Austen’s widening popularity eventually saw Emma included in the Railway Library series published by Routledge in 1870. This “yellowback” edition was the product of George Routledge’s venture into cheap series book publishing.

The Railway editions – intended for travel reading – commonly featured a wood-engraved illustration on the front cover and a back crammed with advertisements telling readers to purchase “Fry’s Pre Concentrated Cocoa” or “Use Pears’ Soap for the Skin and Complexion”.

Imperial Austen

By mid-century, Austen’s Emma was also making an appearance as far away as India. A quick glance at the British Library archives reveals an 1857 advertisement in The Bombay Times and Journal of Commerce for copies of Jane Austen’s Emma, “Just Received Overland – Per Steamer ‘Bombay’”.

In 1886, The Times of India advertised Emma as part of the Bentley’s Favourite Novels series, “the only complete edition other than the [famous] Steventon edition”.

It should be noted that Thomas Macauley – the historian, colonialist, and author of the infamous Minute on Indian Education, 1835 – was also a self-proclaimed Jane Austen fan.

Macauley’s Education Minute set out the British plan to create a class of Anglicised Indians who would serve as cultural intermediaries between themselves and the subjugated Indians, primarily through the introduction of subjects such as English literature (at the time, only Classics were taught in the schools and universities of the English metropolis).

This suggests that there may be a need for a scholarly history of the colonial reception of Austen that has, to date, only been partially written.

Despite the reclamation of Austen’s work in feminist literary studies, there is no doubt that Austen was often packaged historically as “suitable reading” for young women, and as a corrective in female conduct.

In 1884, for example, The Times of India reproduced an article from The Guardian praising Austen’s heroines as models of dutiful daughterly conduct. Even Emma – “the most independent of them,” according to the author – should be praised for her utter absence of opinions, notions or ideas “beyond home duties and occupations”.

Chocolate Box Emma

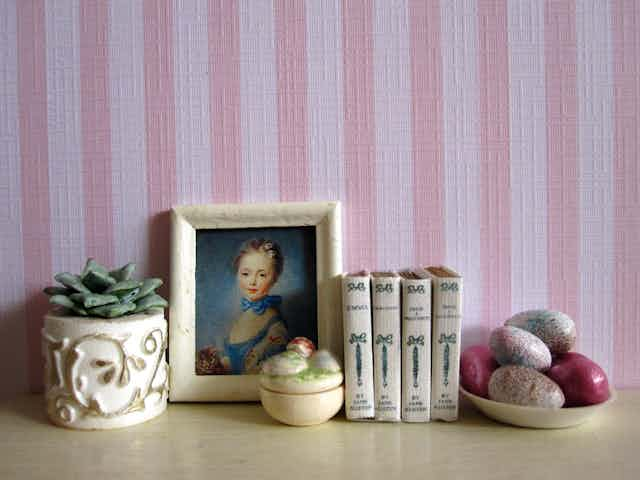

From the late 19th century onwards, marketing Austen’s novels to young women undoubtedly shaped the idea and image of Austen. The novels were increasingly sold as gift sets, with lavish gilt-edged pages and chocolate box illustrations, and these sometimes expensive but also moderately priced editions leave the critic wondering if they were not so much for actual reading as for browsing or display.

In 1898, JM Dent issued a set with colour plates by Charles Brock and his brother Henry Brock, featuring a well-known set of illustrations that were reprinted on a number of occasions in the United States, often in cheaper editions, with shallower colour-plates.

The Brock illustrations, together with the editions illustrated by Hugh Thompson, provide most frequently reproduced visual interpretations of Emma in this period.

In 1948, a new illustrated edition arrived on the market. Philip Gough’s illustrations epitomised the popular Emma. Perhaps it was no coincidence that he was also commissioned to illustrate the Regency novels of the bestselling romance writer, Georgette Heyer.

From the Penguin edition to the post-colonial

In the 1960s, covers of Emma began to shift away from the vogue for illustration. The covers took on a thoughtful quality, reflecting, perhaps, the new seriousness accorded Austen’s work by influential scholars F.R. Leavis and Ian Watts, and, of course, the appearance of R.W. Chapman’s authoritative versions of the text earlier in the century.

The trend was set by the famous Penguin edition that has continuously adorned the schoolrooms of the United States and Australia, and which emphasised historical and social perspectives on the work through reproductions of contemporary paintings and portraits.

The 1966 Penguin Emma was represented by Marcia Fox, painted by Sir William Beechey, the artist appointed court portraitist by Queen Charlotte – the same portrait that more famously adorns the cover of both Pride and Prejudice, and Pride and Prejudice and Zombies (2009), decades later.

David Gilson’s monumental 1982 Austen bibliography indicates that there was a further internationalisation of Austen in the 20th century. For the period of the 1960s, he lists an Arabic Immā (1963), two Chinese I ma (1958 and 1963), as well as a Serbo-Croatian (1954), a Turkish (1963), and a Tamil one (1966).

But perhaps the most striking feature of the massive 20th-century diffusion of Austen is the suspicion that it may have been fuelled as much by Hollywood as by Austen’s canonisation by F.R. Leavis and the Leavisites.

In the 20th century, Emma reached a pinnacle of popularity when it was updated for the Hollywood film Clueless (1995), before the clock was wound back once again to the Regency for the Hollywood version featuring Gwyneth Paltrow (1996) and the British Heritage version written by Andrew Davies for the BBC (1996).

More recently, Emma has featured as a Marvel comic book (2011), adapted by Nancy Butler. It has appeared in updated form in a recently released novel by Alexander McCall Smith who joins novelists Val McDermid and Joanna Trollope as a writer in a HarperCollins venture called The Austen Project.

Unforgettably, in 2014 Emma was transformed into the ultimate in digital chic – a multi-platform web series by the production company Digital Pemberley titled Emma Approved and featuring another modern Emma gainfully employed as a Life Coach who is confronted with the need to, in new-age Life Coach speak:

make amends for the wrongs I have done [and] put the needs of those I care about before my own.

But perhaps the most intriguing of the recent updates are the post-colonial Emmas who collectively signal a cultural reinvention of Austen far beyond the Anglophone world. Hanabusa Yoko produced a Manga version of Emma, distributed by Tokyo-based Ohzora Publishing under their Romance Comics imprint. And in Aisha (2010), Indian director Rajshree Ojha relocates Highbury to Dehli to generate yet another contemporary Emma seemingly afflicted by the problem of “Austen-tacious” consumption, pursuing, among other things, an obsession with western fashion labels from Prada to Dior.

Aisha, wrote Dehli-based film critic Kaveree Bamzai in 2010, is “all about money”.

Not vulgar money […] But older money, which comes with a Delhi Gymkhana membership and yoga lessons with an accented coach.

Austen too, is all about money – or what literary critics have more delicately called the “money plot”. Her novels are essentially about young women, who, in socially constricted circumstances, need to find a way to get along.

Ultimately, perhaps, what the many Emmas of the last 200 years reveal is that Austen’s idea for a novel based on “three or four families in a country village” is shaping up to be immortal.

And the reader might conclude that wherever you stand on the politics of Austen – and the wildly disparate uses to which these Emmas have been put – she is, indeed, a writer of seldom paralleled wit and brilliance.