It has been a big 12 months for Australian small publishers, who have swept what are arguably the three most important national literary awards. Sydney press Giramondo published Alexis Wright’s biography Tracker, winner of the 2018 Stella Prize; Melbourne’s Black Inc. published Ryan O’Neill’s Their Brilliant Careers, which won the 2017 Prime Minister’s Literary Award for Fiction; and Josephine Wilson’s Extinctions (University of Western Australia Publishing) won the 2017 Miles Franklin Literary Award.

Another work from a small publisher, A. S. Patric’s Black Rock White City (Transit Lounge) also won the Miles Franklin in 2016. Small publishers have dominated these awards’ shortlists as well, comprising 80% of the shortlisted titles for the last Miles Franklin and Prime Minister’s awards and 66% of the shortlisted titles for the last Stella.

This is a significant reversal: these awards have historically been dominated by large publishers. Since 2000, for example, only 21% of shortlisted titles for the Miles Franklin have been published by small publishers.

There are dozens of important and respected Australian literary prizes, which help to solidify authors’ reputations and subsidise their writing (this is not an exaggeration; as Bernard Lahire has demonstrated through sociological surveys in France even most “successful” authors draw the majority of their income through other, and often unrelated, work).

But these three awards — the Stella, the Miles Franklin, and the Prime Minister’s — are particularly important because they have broader recognition among the media and the reading public. These three prizes not only increase authors’ and publishers’ status within the literary field but also tend to increase book sales. This is particularly important for smaller publishers, where one successful book can cross-subsidise the publication of many others.

Small publishers have a long history in Australia, and have played a culturally important role. Many of Australia’s most famous contemporary writers started out at small publishers. Peter Carey’s early books were all published by University of Queensland Press. Helen Garner’s Monkey Grip (1977) was published by the influential small publisher McPhee-Gribble, which launched the careers of many other notable writers before being wholly acquired by Penguin in 1989. While large multinationals dominated much of the market for Australian literary fiction in the 1980s and 1990s, small publishers started to become particularly important in Australian literature again in the 2000s.

Retreat of the large publishers

There are many reasons why larger publishers have moved away from literary publishing, as Mark Davis discussed in his 2006 essay The Decline of the Literary Paradigm in Australian Publishing. As Davis argued, the big drivers of this change were increased competition and the rise of data-based decision making among publishers. With the appearance of book data provider Nielsen BookScan in Australia, publishers suddenly had good and fast data on what kinds of titles were selling and which weren’t.

Moreover, the rise of literary blockbusters in the 1990s, including series such as Harry Potter and, more recently, Twilight, has had a huge impact on the way publishers do their business. Blockbuster titles are worth an inordinate amount of the market. For example, Fifty Shades of Grey, at one point, sold one million copies in four days; a novel in Australia is usually considered successful if it sells 6,000 copies in total.

Not only do blockbusters sell in greater numbers, but the marginal costs associated with manufacturing books decrease as more are sold. For these reasons, large publishers have increasingly chased bestselling titles, rather than investing in literary works. The latter, although culturally important, rarely become blockbusters, unless they have won a major award or been adapted into a successful film or television series.

The retreat of large publishers from literary publishing is particularly visible in their virtually non-existent investments in low-selling but culturally significant forms, such as short stories or poetry. While large publishers occasionally publish high-profile collections of short stories, like Nam Le’s The Boat (Penguin, 2007) or Maxine Beneba Clarke’s Foreign Soil (Hachette, 2014), they rarely bring out more than one or two such collections per year. Large publishers have basically no investment whatsoever in contemporary poetry publishing. Australian poetry, in particular, is kept in circulation by a handful of small publishers, such as Giramondo, Cordite, UWA Publishing, Five Islands, and Puncher & Wattmann.

Large publishers’ withdrawal from these areas of literary publishing has also left space for smaller ones to flourish. On the one hand, it has meant that a number of well-known Australian writers have decided to publish their later works with smaller publishers. J.M. Coetzee, Helen Garner, and Murray Bail, for instance, publish their books with Text in Melbourne. Gerald Murnane and Brian Castro publish with Sydney-based Giramondo, while Amanda Lohrey has published her last several books with Black Inc.

On the other hand, small publishers have also been very good at identifying new and unique voices. Steven Amsterdam’s first novel, Things We Didn’t See Coming (2009), was published by the (now-defunct) Melbourne small publisher Sleepers Publishing, and went on to win the (also defunct) Age Book of the Year award. More recently, the Melbourne-based literary journal The Lifted Brow has entered into book publishing, and had great success in selling overseas rights to Shaun Prescott’s The Town (2017). It has just published a new work, Axiomatic, by the lauded author Maria Tumarkin.

Small publishers have become so important within Australia that, as I have argued elsewhere, they now publish the majority of Australian fiction and probably have done so for about a decade. Despite their significance, they have not had particularly great success with major awards like the Miles Franklin and Prime Minister’s until quite recently. But these trends appear to be changing.

Crunching the numbers on major prizes

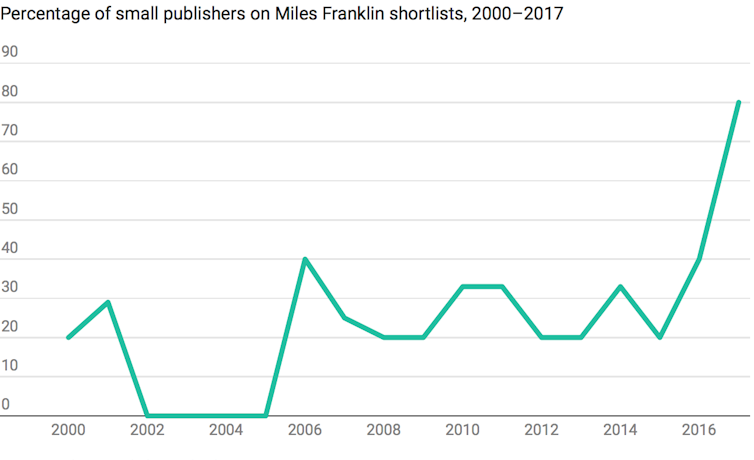

The chart below shows a strong upward trend for small publishers over the past two years in relation to titles shortlisted for the Miles Franklin. While the historical average since 2000 was only 21% of shortlisted titles coming from small presses, this jumped to 40% in 2016 and 80% in 2017. This is a particularly dramatic spike, and I would be surprised if small presses continued to dominate at this rate, but there are good reasons to believe that the general trend is real.

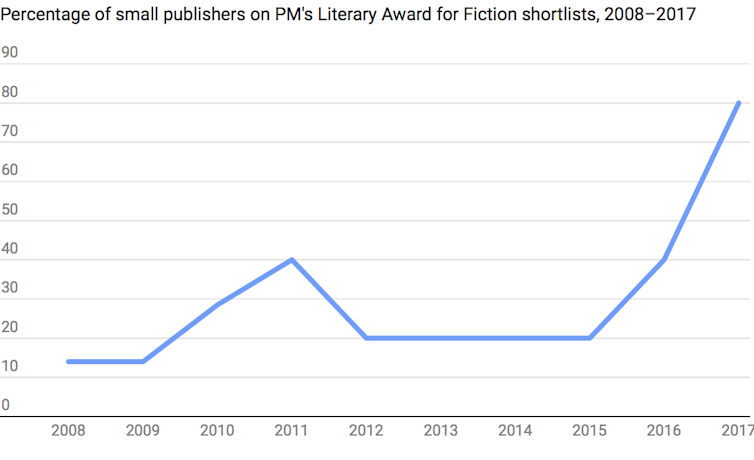

Indeed, the shortlisting data from the Prime Minister’s Literary Award for Fiction shows a nearly identical trajectory to the Miles Franklin data over the last two years, as the chart below illustrates. Like the Miles Franklin, this award saw a jump in shortlisted small press titles in 2016 (40%) and 2017 (80%). In 2017, in fact, both awards shortlisted the same four small press titles: Josephine Wilson’s Extinctions (UWA Publishing), Ryan O’Neill’s Their Brilliant Careers (Black Inc.), Mark O’Flynn’s The Last Days of Ava Langdon (University of Queensland Press), and Phillip Salom’s Waiting (Puncher & Wattmann).

On the one hand, this suggests an enormous shift in the way that the Prime Minister’s award values small publishers; on the other, the unusual — and even bizarre — correlation between the shortlists of the Miles Franklin and the Prime Minister’s awards suggest that this particular instance of small press dominance may be to some degree anomalous. Regardless, the trends are clear, and are also supported by data I have collected on longlisted titles for the latter two awards, which match the trends in the shortlist data.

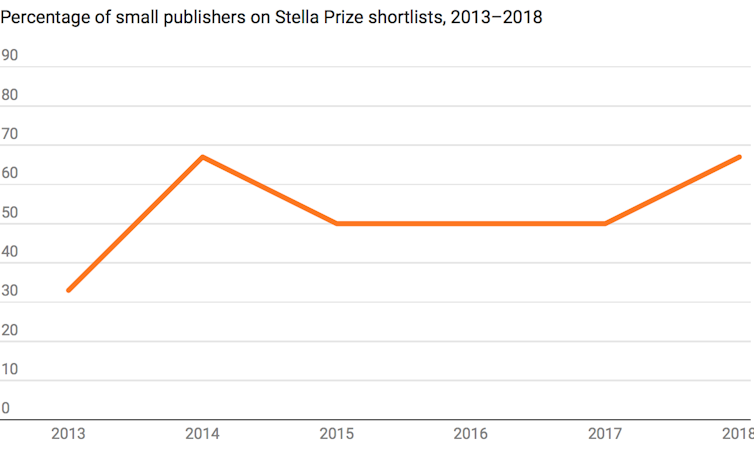

The Stella Prize longlists and shortlists have also recognised small publishers, as you can see in the chart below. Moreover, despite a lower result for small presses in the Stella’s inaugural year (33% in 2013), at least half of its shortlisted titles have been produced by small publishers in every year since.

Small publishers comprise a slim majority of Stella Prize shortlisted titles, with 19 of the 36 shortlisted works (53%) coming from them. Similarly, three of the six winning titles have been produced by small publishers (Text, Giramondo, and Affirm Press). In other words, the Stella Prize has recognised small presses at effectively double the rate of both the Miles Franklin and the Prime Minister’s awards. The dominance of small publishers in the Stella is also replicated in the longlists, with 40 of 72 titles (55%) being produced by small publishers.

Small publisher acceptance

There are material reasons why the Stella Prize has probably been more open to small publishers. Co-founder and former executive director Aviva Tuffield is a highly regarded editor, who has worked at small publishers such as Scribe, Affirm, and Black Inc. Current General Manager (and original Prize Manager) Megan Quinlan previously worked at Text Publishing and The Monthly (which has the same ownership as Black Inc.) Many of the Stella Prize judges past and present, such as Tony Birch and Julie Koh, have published their fiction solely through small publishers.

It is also not coincidental that a prize championing women’s writing and gender equity would recognise small publishers. Indeed, these publishers, as Sarah Couper has demonstrated, have a significantly higher proportion of women in executive roles than large publishers do.

I suspect, too, that small publishers are probably more inclusive both in terms of the authors they publish and the kinds of views and perspectives they present. In this sense, the dominance of small publishers’ titles in the Stella is unsurprising given that it is an award that seeks to champion diversity as well as literary quality.

The Stella’s tendency to recognise small publishers has probably influenced the other prizes to do the same. The routine appearance of such works on the Stella lists has normalised the recognition of small press books by prestigious prizes and thus made it more acceptable for other such prizes to do so. While it’s unlikely that small presses will continue to dominate the major prizes at this rate, I nonetheless suspect that they will continue to be taken much more seriously by such awards than they have been in the past.