Reality television shows based on surgical transformations, such as The Swan and Extreme Makeover, were not the first public spectacles to offer women the ability to compete for the chance to be beautiful.

In 1924, a competition ad in the New York Daily Mirror asked the affronting question “Who is the homeliest girl in New York?” It promised the unfortunate winner that a plastic surgeon would “make a beauty of her”. Entrants were reassured that they would be spared embarrassment, as the paper’s art department would paint “masks” on their photographs when they were published.

Cosmetic surgery instinctively seems like a modern phenomenon. Yet it has a much longer and more complicated history than most people likely imagine. Its origins lie in part in the correction of syphilitic deformities and racialised ideas about “healthy” and acceptable facial features as much as any purely aesthetic ideas about symmetry, for instance.

In her study of how beauty is related to social discrimination and bias, sociologist Bonnie Berry estimates that 50% of Americans are “unhappy with their looks”. Berry links this prevalence to mass media images. However, people have long been driven to painful, surgical measures to “correct” their facial features and body parts, even prior to the use of anaesthesia and discovery of antiseptic principles.

Some of the first recorded surgeries took place in 16th-century Britain and Europe. Tudor “barber-surgeons” treated facial injuries, which as medical historian Margaret Pelling explains, was crucial in a culture where damaged or ugly faces were seen to reflect a disfigured inner self.

With the pain and risks to life inherent in any kind of surgery at this time, cosmetic procedures were usually confined to severe and stigmatised disfigurements, such as the loss of a nose through trauma or epidemic syphilis.

The first pedicle flap grafts to fashion new noses were performed in 16th-century Europe. A section of skin would be cut from the forehead, folded down and stitched, or would be harvested from the patient’s arm.

A later representation of this procedure in Iconografia d’anatomia published in 1841, as reproduced in Richard Barnett’s Crucial Interventions, shows the patient with his raised arm still gruesomely attached to his face during the graft’s healing period.

As socially crippling as facial disfigurements could be and as desperate as some individuals were to remedy them, purely cosmetic surgery did not become commonplace until operations were not excruciatingly painful and life-threatening.

In 1846, what is frequently described as the first “painless” operation was performed by American dentist William Morton, who gave ether to a patient. The ether was administered via inhalation through either a handkerchief or bellows. Both of these were imprecise methods of delivery that could cause an overdose and kill the patient.

The removal of the second major impediment to cosmetic surgery occurred in the 1860s. English doctor Joseph Lister’s model of aseptic, or sterile, surgery was taken up in France, Germany, Austria and Italy, reducing the chance of infection and death.

By the 1880s, with the further refinement of anaesthesia, cosmetic surgery became a relatively safe and painless prospect for healthy people who felt unattractive.

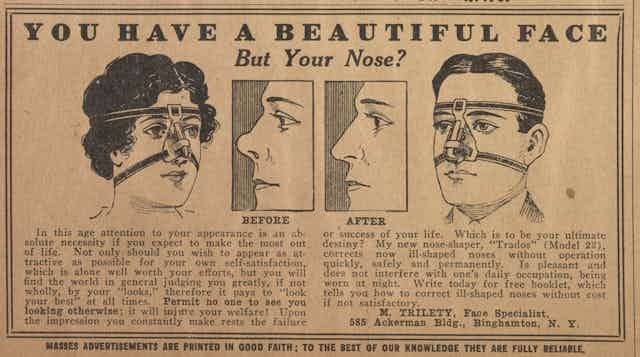

The Derma-Featural Co advertised its “treatments” for “humped, depressed or … ill-shaped noses”, protruding ears, and wrinkles (“the finger marks of Time”) in the English magazine World of Dress in 1901.

A report from a 1908 court case involving the company shows that they continued to use skin harvested from – and attached to – the arm for rhinoplasties.

The report also refers to the non-surgical “paraffin wax” rhinoplasty, in which hot, liquid wax was injected into the nose and then “moulded by the operator into the desired shape”. The wax could potentially migrate to other parts of the face and be disfiguring, or cause “paraffinomas” or wax cancers.

Advertisements for the likes of the the Derma-Featural Co were rare in women’s magazines around the turn of the 20th century. But ads were frequently published for bogus devices promising to deliver dramatic face and body changes that might reasonably be expected only from surgical intervention.

Various models of chin and forehead straps, such as the patented “Ganesh” brand, were advertised as a means for removing double chins and wrinkles around the eyes.

Bust reducers and hip and stomach reducers, such as the J.Z. Hygienic Beauty Belt, also promised non-surgical ways to reshape the body.

The frequency of these ads in popular magazines suggests that use of these devices was socially acceptable. In comparison, coloured cosmetics such as rouge and kohl eyeliner were rarely advertised. The ads for “powder and paint” that do exist often emphasised the product’s “natural look” to avoid any negative association between cosmetics and artifice.

The racialised origins of cosmetic surgery

The most common cosmetic operations requested before the 20th century aimed to correct features such as ears, noses and breasts classified as “ugly” because they weren’t typical for “white” people.

At this time, racial science was concerned with “improving” the white race. In the United States, with its growing populations of Jewish and Irish immigrants and African Americans, “pug” noses, large noses and flat noses were signs of racial difference and therefore ugliness.

Sander L. Gilman suggests that the “primitive” associations of non-white noses arose “because the too-flat nose came to be associated with the inherited syphilitic nose”.

American otolaryngologist John Orlando Roe’s discovery of a method for performing rhinoplasties inside the nose, without leaving a tell-tale external scar, was a crucial development in the 1880s. As is the case today, patients wanted to be able to “pass” (in this case as “white”) and for their surgery to be undetectable.

In 2015, 627,165 American women, or an astonishing one in 250, received breast implants. In the early years of cosmetic surgery, breasts were never made larger.

Breasts acted historically as a “racial sign”. Small, rounded breasts were viewed as youthful and sexually controlled. Larger, pendulous breasts were regarded as “primitive” and therefore as a deformity.

In the age of the flapper, in the early 20th century, breast reductions were common. Not until the 1950s were small breasts transformed into a medical problem and seen to make women unhappy.

Shifting views about desirable breasts illustrate how beauty standards change across time and place. Beauty was once considered as God-given, natural or a sign of health or a person’s good character.

When beauty began to be understood as located outside of each person and as capable of being changed, more women, in particular, tried to improve their appearance through beauty products, as they now increasingly turn to surgery.

As Elizabeth Haiken points out in Venus Envy, 1921 not only marked the first meeting of an American association of plastic surgery specialists, but also the first Miss America pageant in Atlantic City. All of the finalists were white. The winner, 16-year-old Margaret Gorman, was short compared to today’s towering models at five-feet-one-inch (155cm) tall, and her breast measurement was smaller than that of her hips.

There is a close link between cosmetic surgical trends and the qualities we value as a culture, as well as shifting ideas about race, health, femininity and ageing.

Last year was celebrated by some within the field as the 100th anniversary of modern cosmetic surgery. New Zealander Dr Harold Gillies has been championed for inventing the pedicle flap graft during the first world war to reconstruct the faces of maimed soldiers. Yet, as is well documented, primitive versions of this technique had been in use for centuries.

Such an inspiring story obscures the fact that modern cosmetic surgery was really born in the late 19th century and that it owes as much to syphilis and racism as to rebuilding the noses and jaws of war heroes.

The surgical fraternity – and it is a brotherhood, as more than 90% of cosmetic surgeons are male— conveniently places itself in a history that begins with reconstructing the faces and work prospects of the war wounded.

In reality, cosmetic surgeons are instruments of shifting whims about what is attractive. They have helped people to conceal or transform features that might make them stand out as once diseased, ethnically different, “primitive”, too feminine, or too masculine.

The sheer risks that people have been willing to run in order to pass as “normal” or even to turn the “misfortune” of ugliness, as the homeliest girl contest put it, into beauty, shows how strongly people internalise ideas about what is beautiful.

Looking back at the ugly history of cosmetic surgery should give us the impetus to more fully consider how our own beauty norms are shaped by prejudices including racism and sexism.