Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains images and names of deceased people.

Australians love their war heroes. Our founding myth centres on the heroism of the ANZACs. Our Victoria Cross recipients are considered emblematic of our highest virtues. We also revere our dissident heroes, such as Ned Kelly and the Eureka rebels. But where in this pantheon are our Black war heroes?

If it’s underdog heroism we’re after, we need look no further than the warriors who resisted the invasion of their homelands between 1788 and 1928. And none distinguished himself more than Tongerlongeter — the subject of a new book I have written with historian Henry Reynolds.

Tongerlongeter’s story

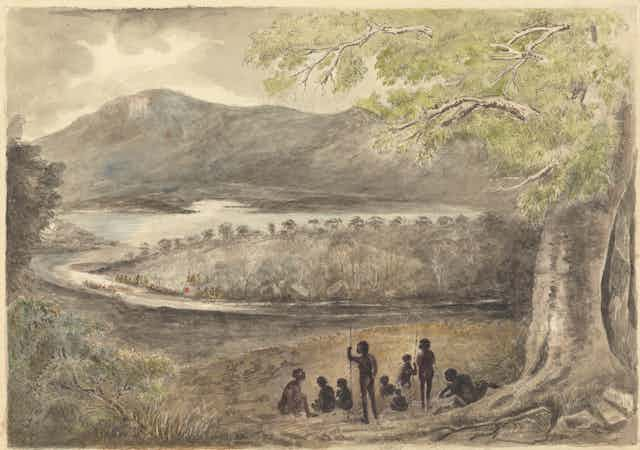

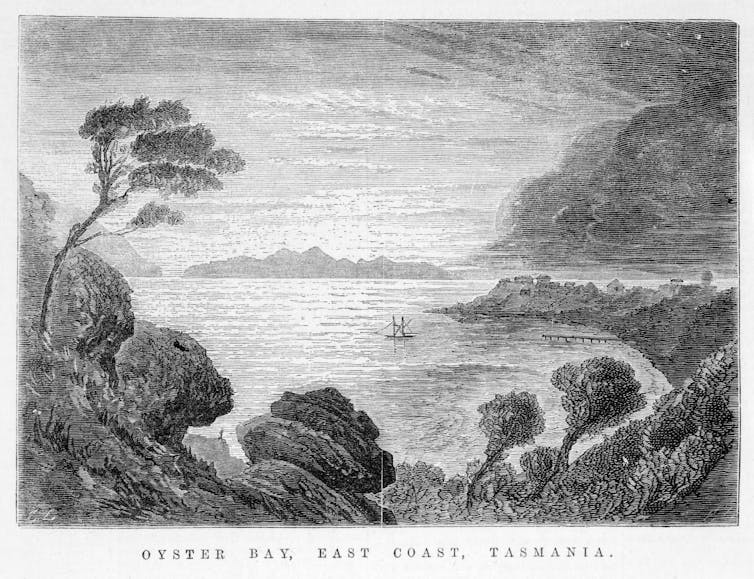

In Tasmania’s “Black War” of 1823–31, Tongerlongeter led a stunning resistance campaign against invading British soldiers and colonists. Leader of the Oyster Bay nation, he inspired dread throughout the island’s southeast. Convicts refused to work alone or unarmed, terrified settlers abandoned their farms, the economy faltered and the government seemed powerless to suppress the violence.

It was a legacy Tongerlongeter could never have imagined in 1802, when his people encountered the French explorers under Nicolas Baudin on Maria Island. Having never heard of foreign lands or peoples, they concluded the pale-faced visitors were ancestral spirits returned from the dead. If zombies are an apt comparison, they were soon to experience a zombie invasion.

The British established their first settlement at Risdon Cove, opposite today’s Hobart, in 1803. Only from the 1820s did settlement accelerate up the fertile valleys of the southeast. Tongerlongeter initially restricted his warriors to targeted retribution, but as the violence intensified, all stops were pulled.

By night, Tongerlongeter and his people were vulnerable to ambushes. Gangs of frontiersmen and sealers killed hundreds of men and abducted countless women and girls. Tongerlongeter’s first wife was taken in just such an ambush.

Being wary of evil spirits, Tongerlongeter’s people never attacked by night. But from sun-up to sun-down, exposed colonists lived in constant fear of attack. Using sophisticated tactics such as reconnaissance, decoys, flanking and pincer manoeuvres, sabotage, and arson, Tongerlongeter’s war parties attacked hut after hut, and often several at a time.

Trained from infancy in the arts of war, Aboriginal warriors carried out guerrilla operations with extraordinary discipline and strategy. Apart from soldiers, most colonists were woefully unprepared to face such assailants. Typically, warriors would surround a hut, then kill its occupants, plunder whatever they wanted, and set it alight. Then they “simply vanished”, outwitting even mounted pursuit parties.

In 1828, as the body count rose, Lieutenant Governor George Arthur declared martial law. Vigilantes had long “hunted the blacks” with impunity; now they did so legally.

While such measures took a devastating toll, Tongerlongeter and his allies, the neighbouring Big River nation, only intensified their resistance, making 137 documented attacks in 1828, 152 in 1829, and 204 in 1830. Each year they refined their tactics. Some settlers insisted the colony should be abandoned.

Read more: Friday essay: Truganini and the bloody backstory to Victoria's first public execution

Drawing a line

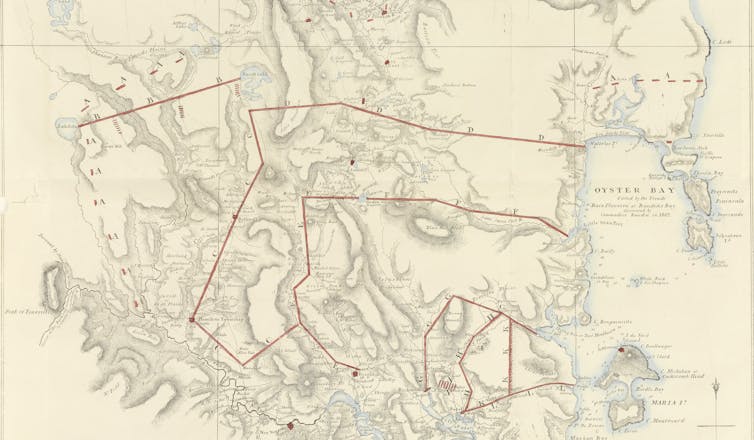

In September 1830, under mounting pressure, Arthur initiated a massive military operation designed to crush the resistance of Tongerlongeter and his allies.

The Black Line, as it came to be known, was Australia’s largest ever domestic military offensive. It involved 2,200 soldiers, settlers and convicts — 10% of the white population — in a seven-week campaign designed to “capture the hostile tribes”. Outnumbered by about 200 to one, and using only traditional weapons, Aboriginal resistance had driven the colony to take the most desperate of measures.

Commanded by Arthur himself, the Black Line was a human cordon, sweeping down eastern Tasmania. It was also a stunning failure, resulting in just two Aboriginal people captured and two killed. During the same period, Oyster Bay-Big River warriors killed five colonists and wounded six.

Still, the white men had made an impressive show of force, so Tongerlongeter’s people headed for the relative safety of the Central Plateau.

They didn’t make it unscathed. According to Tongerlongeter, who recounted his wartime experiences years later in exile, he

[…] was with his tribe in the neighbourhood of the Den Hill and that there was men cutting wood. The men were frightened and run away. At night they came back with plenty of white men (it was moonlight), and they looked and saw our fires. Then they shot at us, shot my arm, killed two men and three women. The women they beat on the head and killed them; they then burnt them in the fire.

A musket ball almost severed Tongerlongeter’s arm just below the elbow. As his comrades sliced off what remained of his limb, the chief’s pain would have been stupefying. But worse was to come. We know from post-mortem records that someone, presumably using abrasive rock, ground smooth his splintered forearm bone. To stem the bleeding, Tongerlongeter simply said his kinfolk “burnt the end”, belying the true horror of cauterisation without anaesthetic.

The desperate final year

Miraculously, Tongerlongeter survived and made it to the plateau, but the momentum of the resistance waned. Oyster Bay and Big River bands made only 57 attacks in 1831. Desperate to avoid the white man’s guns, they wintered in the frigid high country.

Then, in the spring of 1831, Tongerlongeter’s people made one last foray to the east coast where they found themselves trapped on the Freycinet Peninsula by more than 100 armed white men. They were again forced to slip past the muskets at night.

Tongerlongeter made a beeline back west where his wife, Droomteemetyer, gave birth to a son. Parperermanener was the last Oyster Bay-Big River child — a delicate flame kindled from the dying embers of his people.

The armistice

On New Year’s Eve 1831, Tongerlongeter’s war-weary remnant, now just 26 in number, were holed up in the remote lake country when they were approached by a small Aboriginal party. They were envoys of George Augustus Robinson’s “friendly mission”, whom Arthur had tasked with “conciliating the hostile tribes”.

Robinson’s terms were: if Tongerlongeter’s people laid down their arms they could, once order was restored, remain on their Country with a government emissary for protection. The chief was undoubtedly suspicious, but the alternative was the wholesale erasure of his people and culture.

When Tongerlongeter’s small band of survivors entered Hobart a week later, the whole town came to witness the spectacle. Spears in hand, they approached Government House, where the governor invited them in. His administration kept meticulous records — but as important as this meeting was, Arthur knew better than to document the promises he made.

Read more: Henry Reynolds: Australia was founded on a hypocrisy that haunts us to this day

Exiled

Ten days later the whole party set sail for Flinders Island. They became dreadfully seasick. Severely dehydrated, Droomteemetyer would have struggled to breastfeed Parperermanener, and soon after disembarking, his tiny body went limp. For the Oyster Bay-Big River remnant, this was no ordinary tragedy. It wasn’t just that a child had died, or even that it was the child of a chief. There were no more children.

Despite the loss of his son, his arm, his country, his way of life and almost everyone he had ever known, Tongerlongeter did not give up hope. As a leader, he couldn’t, and from the outset he was proactive. By popular vote, he represented the exiles in negotiations, settled disputes, provided counsel, distributed justice, and was instrumental in a range of improvements.

In 1834, a visiting missionary identified Tongerlongeter as “the principal chief at Flinders”, where 244 Aboriginal Tasmanians were eventually exiled. When Robinson took command of the settlement in 1835, he immediately recognised the chief’s seniority, renaming him King William after Britain’s reigning monarch.

But good leadership could only do so much. During the five years Tongerlongeter was at the settlement, there were four births but well over 100 deaths, mostly from influenza. On March 21 1837, Tongerlongeter demanded they be allowed “to leave this place of sickness”; and when Robinson hesitated, he asked: “What, do you mean to stay till all the black men are dead?”

It wasn’t just that an “evil spirit” was sickening his people — Tongerlongeter never stopped advocating for their promised return to Country. When that failed, he supported Robinson’s plan for their removal to Victoria, even if the fledgling settlement’s only appeal was that it was not Flinders Island. Some eventually made that journey, but Tongerlongeter was not among them.

Two kings

King William died from illness on the same day as his namesake in Windsor Castle — June 20 1837.

The two men could scarcely have been more different. One led the largest empire on Earth; the other led a small nation of hunter-gatherers. One dispossessed millions of indigenous peoples; the other determinedly resisted dispossession. One died in the comfort of a lavish castle, the other in a draughty hut on an accursed island far from home.

King William was just a character Tongerlongeter played so his people might have a voice.

If he had anything in common with the British monarch, it was that his death produced a comparable tide of shock and sorrow, albeit confined to a shrinking settlement on a tiny island at the edge of the known world.

Read more: Hidden women of history: Wauba Debar, an Indigenous swimmer from Tasmania who saved her captors

Remembrance and The Black War

The Black War, as everyone at the time understood, was just that — a war. Yes, it was a small guerrilla war, but so were most wars throughout history. It’s impossible to overstate its significance for Tasmania and its peoples. The impacts of subsequent wars pale by comparison, and yet these overseas conflicts and their heroes monopolise our commemorative spaces.

How can this be? Almost all those who fought alongside Tongerlongeter were killed in action — not as helpless victims, but as warriors. Theirs was the most effective frontier resistance campaign in Australian history, killing at least 182 invaders and wounding another 176. No less intimidating were their efforts to sabotage the invasion by spearing thousands of sheep and cattle, and burning dozens of homes and crops.

And the impact of their resistance was felt beyond Tasmania. Governor Arthur later wrote it had been “a great oversight that a treaty was not […] made with the natives”, and a chastened Colonial Office took steps not to repeat that mistake. New Zealand’s Treaty of Waitangi, for instance, was due in no small part to Tongerlongeter and his warriors, who taught the British Empire a lesson in the true cost of “free land”.

Tongerlongeter should be recognised as one of our nation’s greatest war heroes. He should be celebrated by politicians and school children alike, and yet almost no one has ever heard of him.

Tongerlongeter showed the “extreme devotion to duty” and “self-sacrifice” that would later make a soldier eligible for the Victoria Cross. He and his warriors fought year after year in the face of staggering odds.

It’s not that these heroes should receive posthumous medals, but they should receive the respect accorded to those who do. Their skin was black, and they wore no uniform, but if the men and women who sacrificed everything in defence of their country do not exemplify our highest virtues, then who does?

It is an Australian quirk that we don’t officially commemorate or memorialise our frontier wars or those who fought in them. When contrasted against memorials to overseas campaigns, this sends a stark message: our country values these foreign conflicts more than those fought on this country, for this country. And it implies our war heroes are all white.

Read more: Friday essay: it's time for a new museum dedicated to the fighters of the frontier wars

Time has come

Other countries are far ahead of us in this regard.

A statue of the Chilean Mapuche leader Caupolicán has commanded an imposing position in the centre of Santiago since 1910. Samuel Sharpe, the leader of the Jamaican slave rebellion, was declared a national hero in 1975. And outside the presidential palace in Buenos Aires, Argentina’s government recently erected a 15-metre bronze statue of indigenous guerrilla fighter Juana Azurduy.

Momentum for commemoration in Australia is building. Aboriginal community groups and elders, with the support of RSL Tasmania, Reconciliation Tasmania and the Hobart City Council, are planning to install a Black War memorial in Hobart’s Cenotaph precinct. When erected, it will be the first of its kind in Australia.

Tongerlongeter and many other heroes of The Black War are buried at the Wybalenna Cemetery on Flinders Island. But rather than being overlooked by an impressive memorial, only thistles adorn their unmarked graves. How Aboriginal people are commemorated or memorialised is the prerogative of their descendants, but admiration for warriors like Tongerlongeter has the potential to transcend race, culture and creed.