Anyone without social media will have been mystified to learn that a great debate has been raging on Twitter in the UK over whether or not the word “gammon” counts as a racist insult. Emma Little-Pengelly, an MP for Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionist Party, tweeted that she was appalled at such racist stereotyping. Others defended it, saying it’s no worse than using “snowflake” to describe the easily offended, politically correct young. Some simply pleaded, “Please tomorrow let the gammon debate be over”. But what exactly is the “gammon debate”?

It all started with a tweet – what else? As the 2017 election results came in, the journalist Ben Davis, dreading the thought of all those triumphant Ukippers and Brexiteers he would doubtless soon be hearing in the pub or in the Question Time audience, got his retaliation in first. “Whatever happens,” he tweeted, “hopefully politicians will start listening to young ppl after this. This Great Wall of gammon has had its way long enough.”

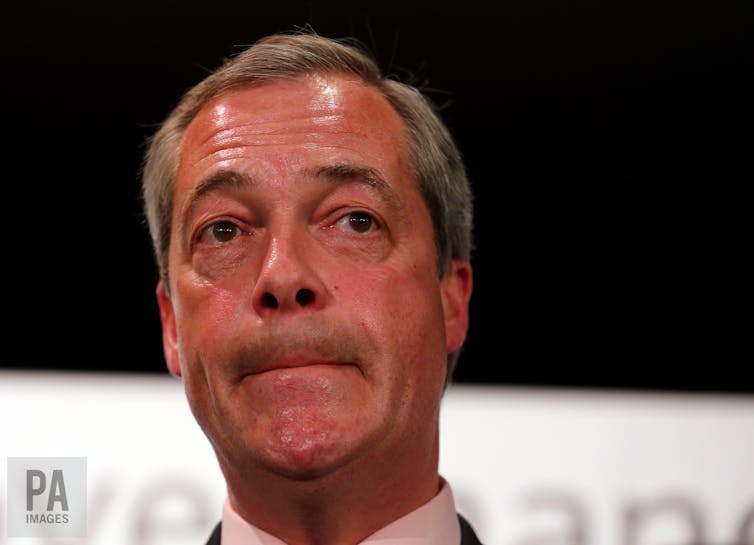

The implication was that the middle-aged white man stereotypically associated with right wing or nationalist politics in the UK, particularly when stirred to rage, bears more than a passing resemblance to a plate of boiled meat. Davis now says he regrets coining the term, having seen how it was later used.

It probably seemed a good phrase at the time, but it opened a twitterstorm. Had Davis invented a new racist term? Some – no doubt going red in the face – argued that he had. Meanwhile, the phrase was being gleefully spread by people who argued that middle-aged white men can hardly portray themselves as a persecuted minority in the UK. Is this just a twitterstorm in a teacup or does it actually matter?

There has always been political name-calling. “Whig” and “tory” were originally insults (some would doubtless say that “tory” still is). Most insults lose their sting over time: “Adullamites”, “pro-Boers”, “squiffites” were all designed to sting in their day, and even Aneurin Bevan’s inflammatory characterisation of the Conservatives as “lower than vermin” has the feel of a period piece.

But words are powerful things and attaching the right label to an opponent can be a handy way to win an argument without having to go to the trouble of presenting a case. Calling someone a “Remoaner”, a “kipper” (for a Ukip supporter), or even “xenophobe” or “racist”, can often be the political equivalent of putting your hands over your ears and saying “la la la”. The image of a delicate “snowflake” vividly captures the inability of some young people to cope intellectually, or even emotionally, with opinions and attitudes different from their own.

These labels do at least describe an attitude or opinion, though. “Gammon” tells us nothing about anyone’s beliefs or outlooks: it’s a slight drawn entirely from a rather unappealing image of how white men look (“gammons” are routinely characterised as men) when they get red in the face with rage. We then deduce their political views – anti-PC, pro-Brexit, xenophobic and so on. A stereotype is born.

Is this offensive? Of course it is. Not only are other colours and genders of Brexiteer available, but, at a time when the Labour party faces serious accusations of deep-rooted antisemitism, it’s perhaps not the best time for the left to be throwing pork-based insults at its critics. In any case, the term’s real tin ear comes in its inability to understand that personal characteristics, over which we have no control, should always be kept out of political discourse, even insults. Calling Neil Kinnock a “Welsh windbag” was alliterative and deadly, but it was still very unfair on the Welsh.

In Victorian times, “gammon” was used to mean “absurd, worthless or manifestly false talk” – not a bad characterisation of Twitter, perhaps. But using it to draw attention to people’s skin colour as a shorthand reference to their views steps over the mark and deserves all the condemnation it has received.