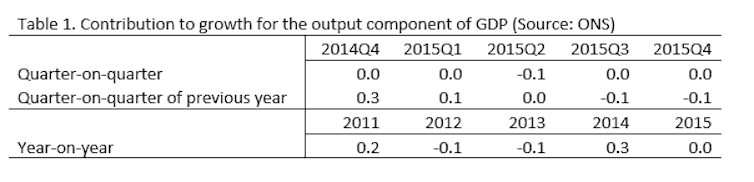

The UK economy is in recovery, according to the latest government figures – but what is, on face value good news, is tempered by concern at the pitifully small contribution made by the manufacturing sector. Growth has been driven almost entirely by the services sector, and in particular by the business services and finance industries.

There is noticeable growth in only two manufacturing industries for which data are readily available: chemicals (and chemical products) and transport equipment. Most other industries have moved sideways between 2010 and 2014.

At a political level, this is problematic on two counts. First, this trend doesn’t alleviate concerns about UK’s exposure to future shocks to the global financial system. Second, the government has raised expectations about a “rebalancing” of the economy towards manufacturing – the chancellor of the exchequer, George Osborne, has made much of creating “a Britain carried aloft by the march of the makers”. But the numbers still don’t seem to bear that out.

Experts have offered a number of explanations about the persistent weakness of the manufacturing sector, some more justifiable than others. These include the persistence of low global demand for goods and commodities, the amount of debt in the household sector and its impact on household consumption, and the strength of the British pound.

Since the figures reported above are not forward-looking by their very nature, they do not tell us whether there are structural factors that could prevent the rebalancing of the economy back towards manufacturing industry and how feasible it would be. The challenge for rebalancing is significant.

Data available from the World Bank suggest that of the major developed and emerging market economies of the world, only South Korea has been able to increase the manufacturing sector’s share of GDP between 1996 and 2014.

While the UK manufacturing sector’s share is considerably lower than that of Germany, it is comparable to that of France and the US. This, in turn, raises the question about the ability of a single country to significantly rebalance its economy in favour of manufacturing when global growth is weak and when many countries – for example, the “Make in India” initiative – are trying to do the same thing.

Finding the right niche

Perhaps the most important question for the UK’s manufacturing sector is where firms and corresponding industries are located along global value chains (GVCs). Recent research from the European Central Bank suggests that as the global production system becomes increasingly dominated by value chains – Apple, for example, has its intellectual property and design in the US, sources its chips from South Korea and assembles its phones, etc, in China – it will be important to “look beyond industries to understand trade and production patterns. Countries [would] specialise in specific business functions involving specific tasks rather than specific industries”.

The strategic focus, correspondingly, would have to be not so much in the development of entire industries but rather to find niche areas of expertise high up in the GVCs of a relatively wide portfolio of industries. This in turn has implications for innovation capacity that is both much discussed and where the UK, with a score of 62.42 for the Global Innovation Index, is ranked second globally – ahead of the US (5th, 60.10), Germany (12th, 57.05), South Korea (14th, 56.26) and Japan (19th, 53.97). While productivity growth continues to be a challenge, therefore, there is at least some evidence that the UK may be well positioned to grab a niche relatively high up GVCs, where much of the value is created.

This brings us to the two issues with huge political implications. First, are we asking the right questions about manufacturing sector growth and its share in the economy? If the future of manufacturing lies in innovation, will we see an inevitable period of industrial decline as industries in which UK firms do not have competitive advantage shrink while new industries and firms grow to make their mark?

Second, what is the objective for growth of the manufacturing sector? Is the objective a more diversified UK economy that is not heavily reliant on the financial sector – or is there an unspoken subtext about generating demand for a well-paid and organised sector labour force harking back to the post- World War II era of manufacturing growth. While innovation-driven manufacturing sector growth may be quite feasible, it may not necessarily lead to the creation of a large number of well-paid jobs for people with all skills levels.

Going it alone?

Then there is the question of how at British exit from the EU might affect all this. While crystal ball-gazing is hazardous, two things immediately come to mind. If the future of UK manufacturing lies in an innovation-led move up the GVC ladder, it would need an economy that encourages innovation and clusters of enterprises that may be costly to develop within borders of a single country whose resources are limited. To the extent that Brexit would raise the transactions cost of forming these eco-systems and clusters in cooperation with other European countries, it would be more prudent to stay in than stay out.

Further, since integration with GVCs quite likely has implications for skill gaps at one end of the labour market and structural unemployment at the other, it may be imperative for the UK to be part of the intra-EU flow of labourers. Retraining of labourers in sunset industries to prepare them for sunrise parts of the sector sounds good in theory – and makes for good political speeches – but it cannot possibly be a substitute for free mobility of labour within 28 countries that will present opportunities for workers with particular skills to find the right niche and industries with particular needs to hire the right workforce.

Policymakers, in other words, would have to have clarity about the objective for manufacturing growth and rebalancing: either achieving greater diversity within our GDP portfolio so that we are not overexposed to future financial crises, or creating the space for a certain kind of employment. Importantly, it would be prudent to make those choices within the the EU.