This article is part of our Gender and Christianity series.

To understand contemporary Christian ideas about gender, and specifically masculinity, we need to go all the way back to the values that shaped Christian origins in the first century.

The pattern across Greek, Roman and Jewish society was that men were the heads of households, and households were the primary economic unit. Women managed the internal affairs, while men managed the external ones.

Read more: Evangelical churches believe men should control women. That's why they breed domestic violence

Most men, at around 30 years old, married a girl barely more than half their age. With such an age difference, the girls were less experienced and less emotionally mature. So men believed themselves to be superior to women – a fallacious conclusion that, to them, seemed obvious.

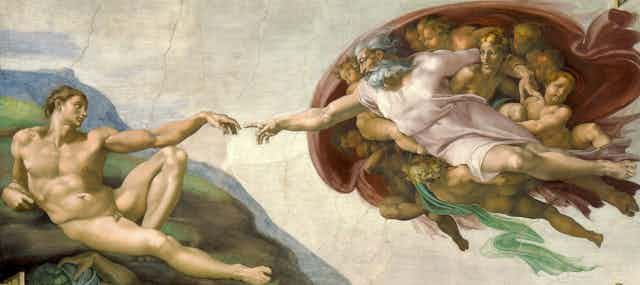

Females were failed males, argued Plato, and people often read Genesis in the Bible as saying man was made in God’s image, while woman was made in man’s.

Paul, one of the most influential Christian leaders, argued that male and female, slave and free, were all loved by God and were one in Christ, but women should dress like women, even in leadership, and should normally leave public discourse to men.

This tension – between equality and the conformity to social norms – still has a long way to go for women in some Christian circles and in the wider community.

Read more: What the early church thought about God's gender

For men, how they saw themselves shaped how they saw God, and they saw God shaped how they saw themselves. This also had implications for how they saw women.

Jesus is the exception

Powerful men, kings and fathers were most often used to portray God. Greek sculpture, Roman macho ideals and oriental images contributed to an image of God who behaved just like such men: he was concerned primarily with power and control and, at best, fatherly benevolence.

Read more: The man who painted Jesus

But other voices challenged such masculine models – including Jesus of Nazareth. In Mark’s gospel, Jesus declares:

The Son of Man came not to be served but to serve and to give his life a ransom for many.

In a three-step narrative, it depicts Jesus’ disciples reflecting traditional aspirations of power, arguing who would be the greatest, wanting the top jobs and trying to persuade Jesus that to be the Messiah he has to win, not lose.

Every time, Jesus refutes their values. Mark then subverts their assumptions by depicting Jesus as a king enthroned on a cross and wearing a crown of thorns. This turned the disciples’ values upside down. Here was a model of being a person, including being a man, which put love and service at the centre.

Elsewhere, Jesus had appealed to parental compassion, arguing we need to see God as caring and compassionate, not as aloof and unforgiving, much less obsessed with power and control.

Such a radical alternative model of masculinity was difficult to sustain.

What often prevailed was the notion that Jesus was, in effect, an exception to the masculine ideal and the way God is. This notion is still alive and well for many today, who see God’s love and forgiveness as only temporary, and believe God will finally resort to violent punishment of those who refused to respond.

Read more: #HimToo – why Jesus should be recognised as a victim of sexual violence

Such violence, sometimes horrendously depicted as being tormented with fire, was deemed fair, because God is just and had made the options clear. This is a view many will still defend.

Two opposing Christian views of masculinity

So there’s not one Christian view of masculinity, but at least two. They are diametrically opposed and reflect two very different understandings of God.

One sees greatness in power and control and the right to exercise violence when one is in the right, and is depicted predominantly in male terms.

The other sees greatness in love and compassion; it confronts violence and abuse of power.

What people value in their God, they value in life. Today, this might mean men can conclude that if they are right, they, too, have the right to be dominating. That may show itself in physical cruelty, but also in the subordination or exclusion of women.

Read more: Forceful and dominant: men with sexist ideas of masculinity are more likely to abuse women

In religious contexts, it can be associated with appeals to the authority of the Bible above reason and reasonable love, whether in church communities or in the home.

But where people give priority to reason and the reasonable love that lies at the heart of the Christian tradition, the effect for both men and women is liberating.

Significant social changes also play a role here. If, in the first century, women were deemed inferior and lived pregnancy to pregnancy, nearly half of them not surviving beyond the age of thirty, over the past half century effective contraception has helped even the playing field for women to engage in leadership as much as men. Though sadly that is still not the case in many communities including churches.

This has gone hand in hand with a reassertion of women’s rights, to the benefit of both women and men.

Read more: Medieval women can teach us how to smash gender rules and the glass ceiling

For many men, schooled in traditional models of masculine superiority, this has caused a crisis of identity.

Despite the advent in the 20th century of pop psychology, which gave men permission to cry, many still have not made it.

Sadness morphs into anger and anger, violence, towards others and sometimes towards themselves. We need to call out the myth of masculine superiority and the abuse it generates.