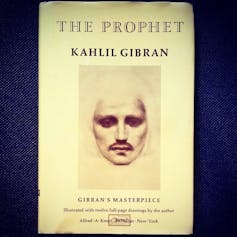

Kahlil Gibran (original spelling at birth “Khalil”) is a strange phenomenon of 20th Century letters and publishing. After Shakespeare and the Chinese poet Laozi, Gibran’s work from 1923, The Prophet, has made him the third most-sold poet of all time.

This slim volume of 26 prose poems has been translated into over 50 languages; its US edition alone has sold over 9 million copies. Its first printing sold out in a month, and later, during the 1960s, it was selling up to 5,000 copies a week.

It has seemingly been able to speak to various generations: from those experiencing the Depression, to the 1960s counter culture, into the 21st century. It continues to sell well today.

What is fascinating about the Gibran/Prophet phenomenon is the bile of critics in the West in relation to the work. Outside of English-speaking countries, the Lebanese-born Gibran attracts far less disdain. Professor Juan Cole, from the University of Michigan, has noted that Gibran’s writings in Arabic are in a very sophisticated style.

The midwife of the New Age

The Prophet is interesting for a number of reasons, not only for its ability to sell. It is written in an archaic style, recalling certain translations of the Bible (Gibran was intimate with both the Arabic and King James versions) and has an aphoristic quality that lends itself to citation — for weddings, funerals, courtships — and accessibility. There are at least two high schools named after its author and it was quoted in a eulogy given at Nelson Mandela’s funeral.

The Prophet declares no clear religious affiliation, while at the same time operating in a quasi-spiritual or inspirational register. Many might even class it in that category of writing known as “wisdom texts”.

Gibran has been referred to as the midwife of the New Age, due to the role The Prophet played in opening a space for spiritual or personal counsel outside organised religion and its official texts. The Prophet appears to embrace all or any spiritual tradition (or at least to exclude none explicitly), and this vagueness or openness (depending on one’s reading) may account for part of its widespread appeal.

The book, which presents advice on a number of core aspects of being human — such as love, parenting, friendship, Good and Evil, and so on — employs a simple narrative device.

An exiled man, Almustafa, who has been living abroad for 12 years, sees the ship that will carry him back “to the isle of his birth” approaching. Filled with grief at his imminent departure, the townspeople gather and beseech him to give them words of wisdom to ease their sorrow:

In your aloneness you have watched with our days, and in your wakefulness you have listened to the weeping and laughter of our sleep.

Now therefore disclose us to ourselves, and tell us all that has been shown you of that which is between birth and death.

Gibran himself had been in the US for 12 years at the time of writing and, it could be argued, was in a kind of exile from Lebanon, the country of his own birth.

Among many subjects, The Prophet offers contemplations on marriage:

… stand together yet not too near together:

For the pillars of the temple stand apart,

And the oak tree and the cypress grow not in each other’s shadow.

On children:

You may give them your love but not your thoughts

for they have their own thoughts

You may house their bodies but not their souls,

for their souls dwell in the house of tomorrow, which you cannot visit, not even in your dreams.

And pain:

Even as the stone of the fruit must break, that its heart must stand in the sun, so we must know your pain.

The woman behind the poet

Biographers have emphasised Gibran’s tendency to pretension, to self-aggrandising, to fictionalising his own history, and his relations with women such as his sister, Marianna (who supported him with menial work), and especially his patron and confidante, Mary Haskell.

The latter remained devoted to him her entire life and also financed much of his lifestyle, enabling his artistic projects up until and beyond his success with The Prophet. Haskell had a penchant for enabling the less fortunate (although she herself was not wealthy), and Gibran was not her first project of this kind.

She continued to edit his work discreetly well into her own marriage, to which she had resigned herself after their engagement stalled. Gibran had a tendency to get involved, as Joan Acocella writes in her detailed New Yorker piece, with older women who could be useful to him.

He was a beautiful, “oriental” young man. Having grown up, from the age of 12, in the ghettos of Boston’s South End, he survived by hoisting himself, or finding himself flung, into more privileged circles thanks to his looks, his talent (he could paint and write) and his “mysterious” appeal of being the “other”.

Anglo-Americans could, in other words, accessorise with him. And they did. He was “discovered” by Fred Holland Day, a teacher, who dabbled in the worlds of Blavatsky and the occultism that was de jour, and who liked to photograph young men, both in exotic garments and out.

In Gibran’s case, since evidence suggests that he evaded a sexual relation with Haskell, he at least did not leave her with the financial burden of children (not uncommon in his time). He ended his life primarily close to his sole-remaining sibling, Marianna and his secretary, and later biographer, Barbara Young.

Due to the extensive number of edits that Haskell offered on most of Gibran’s works across his career (including his first publication, a short poem), it is almost certain that “his” output — like many artistic achievements — might be more accurately deemed a collaboration. The enduring convention of signing works with a singular name has tended to result in the eclipsing of efforts of crucial contributors, often women.

Death and dualism

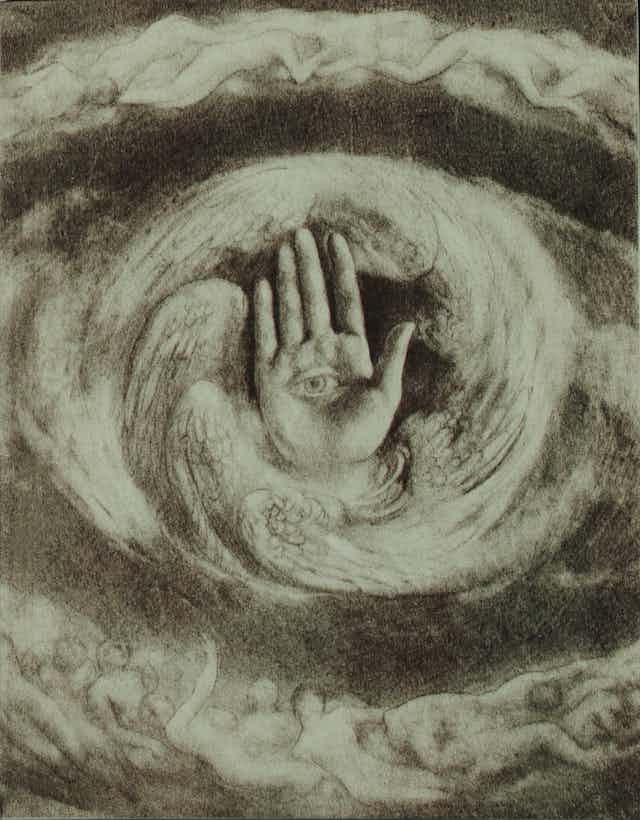

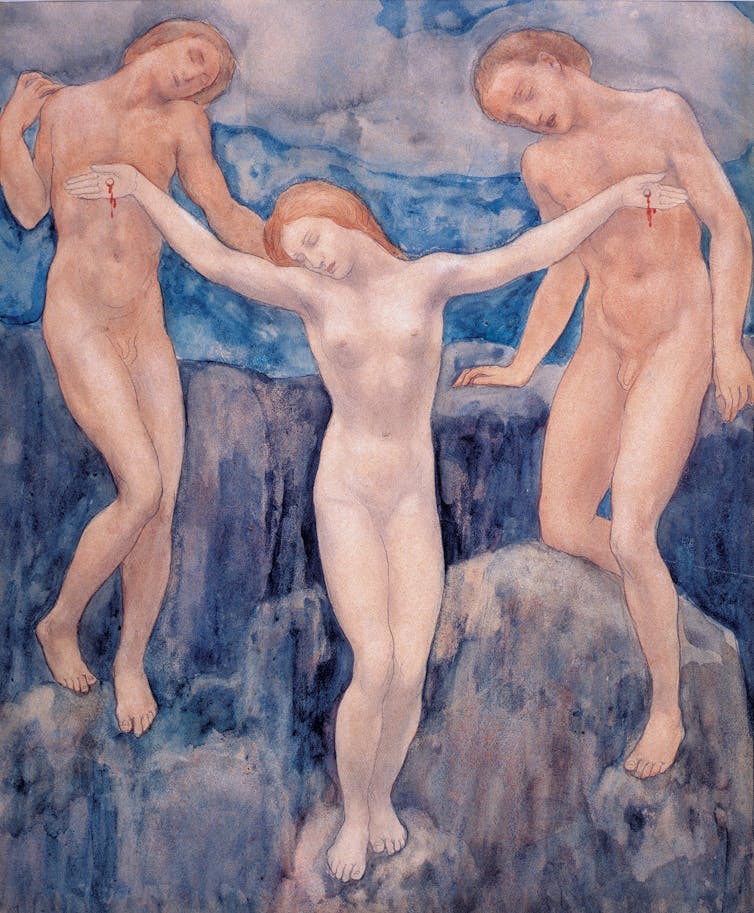

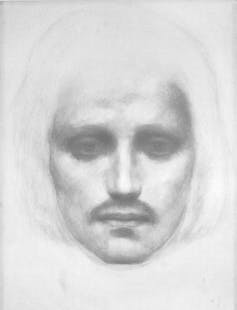

Despite the indifference of Western critics to Gibran’s work, Gibran’s credentials were not shoddy; he was a trained artist (at the Académie Julian) had his first exhibition at 21, and produced over 700 works in his lifetime, including portraits of Yeats, Jung and Rodin.

Gibran died young, at age 48, from cirrhosis of the liver, due to a propensity for large quantities of arak, supplied to him by his sister, Marianna. One wonders whether Gibran was able to find any solace in his own words in his final days of frailty.

In The Prophet, he (and, we could speculate, Haskell) write(s):

Trust the dreams, for in them is hidden the gate to eternity … For what is it to die but to stand naked in the wind and to melt into the sun?

And what is it to cease breathing but to free the breath from its restless tides, that it may rise and expand and seek God unencumbered?

Only when you drink from the river of silence shall you indeed sing.

Gibran has been criticised for his style of playing confoundingly but reassuringly on opposites, which, some argue, can mean anything. (One must note, however, that this unsettling of binary structures is a feature of enduring wisdom texts such as the Tao Te Ching, as well as recalling writings of Sufism and other traditions.)

Furthermore, for the son of destitute immigrants, who rose to fame via his beauty, talent and a blind conviction of his own specialness (which he nourished along with a small obsession with Jesus Christ, the subject of a later, and arguably better work), perhaps life had presented to him its own stark dualities: abjection/acclaim; poverty/wealth; indifference/desire; disdain/popularity; exoticism/racism.

Momentary respite

For someone who undoubtedly “made it” (according to the grim criteria of the New World), Gibran may well have had more than a kernel of wisdom and know-how for those trying to survive its heartless, capricious climes. The fact is that millions of people have found momentary respite in his shifting, evocative words.

In a century where authority figures - whether political or representing various spiritual traditions - have seemed not only to fail their flocks, but to have actively betrayed them, Gibran’s perhaps fuzzy but lyrical advice has come to fill a vacuum of integrity and leadership. We need not badger readers of this work (who included, incidentally, the likes of John Lennon and David Bowie) who might use it to express their love, notate their grief, or ease their existential terrors.

The Prophet has worked as a widespread balm, as effectively as anything quick and concise can. Cheaper than an ongoing tithe to pharmaceutical companies, at $8.55, the going rate at Book Depository, it neither incites hatred, nor violence, nor religious divisiveness.

It says the kinds of things that we sometimes wish a trusted other might say to us, to calm us down. In these aggravated times, perhaps we can appreciate its sheer benignity and leave its boggling success be.

The exhibition, Kahlil Gibran: The Garden of the Prophet, opens at the Immigration Museum, Melbourne, on November 28.