The Water Margin, also known in English as Outlaws of the Marsh or All Men Are Brothers, is one of the most powerful narratives to emerge from China. The book, conventionally attributed to an otherwise obscure Yuan dynasty figure called Shi Nai’an, takes the form of a skein of connected tales surrounding various heroic figures who — persecuted, exploited, wronged, or trapped by venal officials — eventually band together in the fortress of Liangshan (Mount Liang), in the present-day province of Shandong.

Its influence has gone far beyond the usual genres of fiction, film, art, and theatre. The stories provide, even today, a point of reference for codes of honour, social and economic networks, secret societies and political movements.

Generations of China’s governments have sought to represent themselves as guardians of an often explicitly neo-Confucian order characterised by a fixed and morally-grounded political and social order constructed of hierarchical relationships. But The Water Margin represents another, equally real and representative, Chinese worldview. In this world, local injustice is the rule, and defence against cruel local authority is a matter of vengeance, stratagem, and violence.

Read more: Why you should read China's vast, 18th century novel, Dream of the Red Chamber

From this universe, itself a highly mediated depiction of the rapidly decaying Northern Song dynasty in the 12th century, derive fictional worlds of errantry, struggle and righteousness that have gone through endless narrative and cinematic iterations.

Of these descendants, the most familiar today are the fictional worlds of Hong Kong writer Jin Yong, which remain the closest thing to a reading list for adolescents in the Chinese world, and the kung fu genre that has been the global calling card of Sinophone film since at least Bruce Lee.

Rebels with a cause

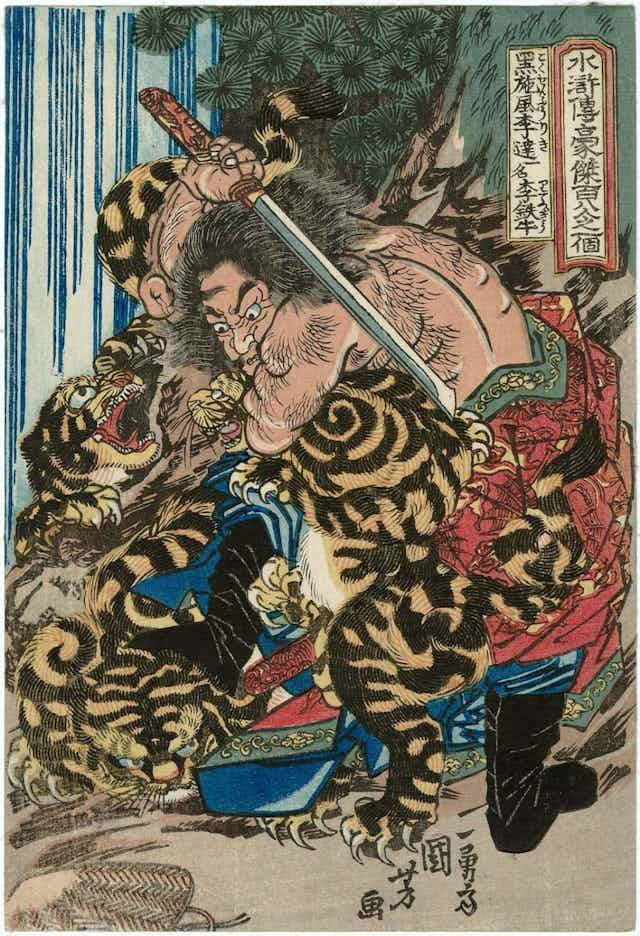

With printed versions dating back to the 14th century, The Water Margin largely follows the adventures of strongmen, innkeepers, footpads, peasants, vagabonds, fishermen, hunters, petty officials and local gentry. Surrounding these protagonists are the thousands of nameless followers and victims who are knocked off or maimed (just as they might be casually dispatched in Homer) in the novel’s thousand-odd pages.

Women, when they (not so very often) appear, are hard-nosed mistresses, pugnacious sisters, hapless wives, strategising helpmeets, or murderous innkeepers (one of whom has hit on Mrs. Lovett’s idea of baking humans into pies a full 800 hundred years before her). This also sets it apart from the mainstream of imperial fiction, which is substantially preoccupied with the passions and travails of high-born, talented women and their ambitious scholar swains, not to mention emperors and generals.

It is only a novel after a fashion: The Water Margin’s text is substantially the record of stories that had already been circulating at the time it was committed to the page. Shi Nai’an’s authorship is little more than a conventional attribution, and the text is far from stable, existing in various versions beginning from the 14th century, two hundred years after the events it depicts. It reached its usual present form in the 17th century.

In the Ming (14th-17th century) and Qing (17th-20th century) dynasties, the bandits of The Water Margin continued to influence all manner of groups operating far from the seat of power, despite periodic attempts to ban the book.

The fact that the villains of the novel are local officials, while the bandits remain at least notionally loyal to the imperial court, has proven an enduring inspiration. Many are the brands of rebellion that have found it practical to be on the other side of the law while retaining a claim to the values of brotherhood, honour, loyalty and patriotism.

Enduring legacy

The plot’s political relevance has never gone away. Having been adopted in the 1930s by reformers as a healthily anti-feudal narrative, it was later deployed in a major 1975 government campaign, in which the leader of the Liangshan bandits in the book, Song Jiang, was criticised for accepting the emperor’s offer of amnesty. Had he not given the game away? And was he therefore not guilty of coexistence with forces inimical to the masses, just as party members, late in the Maoist era, would be guilty of capitulationism if their fervour flagged?

This move, widely interpreted as an effort to head off the fall of the Gang of Four shows how centrally the characters have been retained even in modern and contemporary Chinese consciousness.

Read more: How Conrad’s imperial horror story Heart of Darkness resonates with our globalised times

It’s commonplace to lament human transience and contrast it with the immutability of nature. But those going in search of the dense marshlands of Shandong —- where in the novel crafty fishermen might cause unwary inconvenient minor officials to disappear —- will be disappointed. The entire geography of the novel has been altered beyond recognition by river engineering and irrigation.

This of course does not prevent local governments continuing to put up buildings tagged to certain events in the novel, hoping at the same time that the message of righteous rebellion against local authority is never taken too literally. The formidable, impregnable, fortified mountain, Liangshan, rises just short of 200 metres in reality.

The place of The Water Margin has moved almost entirely into the imaginary, and it is the situations, the events, the stratagems and above all the characters – furious and righteous, looking to set the world right – that have left their mark on posterity.