The United Nations is once again denying proper justice to victims of cholera in Haiti. Perhaps the UN hopes it can make good by apologising, which it did at the end of 2016, and accepting that it was at least partly involved in the initial outbreak of the disease. But this isn’t enough. And while it promises to prevent future outbreaks and offer remedies to victims, its efforts are proving inadequate.

The UN has to put its money where its mouth is – to listen to the individuals it harmed and to provide them with the remedies that they so desperately need.

Since 2004, the UN has maintained a peacekeeping mission (MINUSTAH) to help stabilise and rebuild the country. After a devastating earthquake in 2010, more peacekeepers arrived; the UN did not screen them for cholera, which had never been present in Haiti. Some peacekeeping camps had only inadequate toilet facilities, which were used by Nepalese peacekeepers carrying cholera; as a result, raw cholera-contaminated sewage found its way into Haiti’s main river, the Artibonite, upon which vast numbers of Haitians depend. The disease quickly spread around many parts of the country, and it’s thought to have killed around 10,000 people.

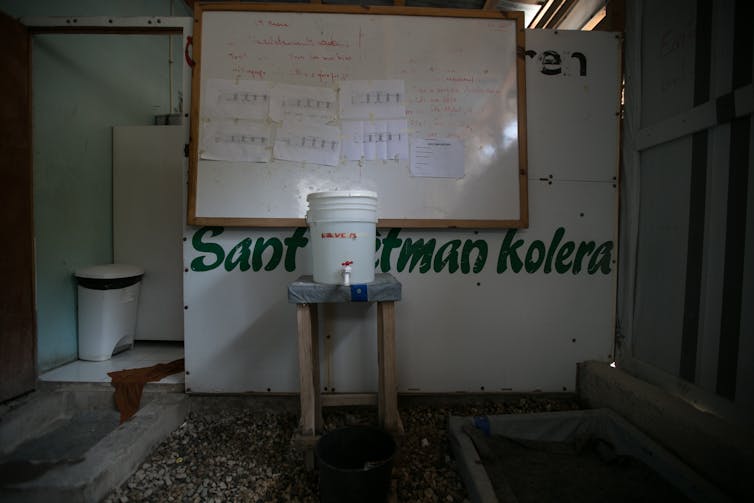

It wasn’t just the initial outbreak that devastated families and communities. The disease was neither contained nor eradicated, and the disease is still present in Haiti today. After years of pressure through advocacy campaigns and a class action lawsuit, the UN has pledged to provide remedies through what it calls a “victim-centred approach”.

But what’s fast becoming apparent is that any consultations with victims will only take place after the UN determines what those remedies will look like. And that means they won’t take into account victims’ own ideas of what they need.

Missing the point

The UN’s plan for Haiti includes both a commitment to consult with victims and a preference for collective reparations, but it’s succeeding on neither front. Building health centres and schools or providing “other collective remedies” may be worthwhile, but it won’t help put victims back in the position they were in before cholera killed and sickened almost one tenth of Haiti’s population. What many of the victims really need is money.

In March 2017, we travelled to Haiti to observe the work of the public interest lawyers who represent the cholera victims. Those victims we met are not seeking vast sums; they are asking for small cash transfers to allow them to buy back land or cattle they had to sell to pay for travel to a hospital, or to pay back the money they had to borrow to bury their dead relatives. They want enough to pay for basic things – getting their children to school, for instance – that they could afford before coping with the cholera outbreak saddled them with debt.

These people told us that they don’t trust either the UN or the state to finish the health centres and schools they’ve promised to build. Even if they are completed, they will hardly solve everyone’s problems. They won’t help families who lost a parent to provide for their children, or to buy back possessions they sold in desperation six years ago.

As one man told us, the projects “will mean that [we] victims see nothing other than big cars driving down the road blowing more dust into our faces”.

Falling short

Providing remedies in the form of cash payments is not unusual, even for the UN. There’s even precedent for giving them out after epidemics: the UN Development Programme recently offered cash transfers to people in Ebola-struck areas of West Africa, not as compensation, but as a means to mitigate the devastating effect of losing breadwinners or taking on debt to pay for treatment.

The UN went to these lengths even though it didn’t cause the Ebola outbreak, so surely it can bring itself to compensate the victims of an epidemic which its peacekeepers were involved in causing. But the UN Development Programme isn’t offering cash payments to Haiti’s cholera victims. Why? Because the money and political will aren’t there.

Whereas the Ebola cash transfers came out of the UN’s budget, money for the cholera effort is meant to come in the form of voluntary donations from UN member states, who have so far collectively contributed only a tiny percentage of the target amount. This is yet another slap in the face for the victims: the UN played a role in causing the outbreak, and its budget can certainly spare the money required.

Is this behemoth of an organisation really so worried about the consequences of giving a couple of hundred dollars each to some of the poorest people in the world? This epidemic is a terrible stain on the reputation of the UN and its peacekeeping missions, and it will only be removed if a proper resolution package is created and implemented.

And whatever form that package takes, it must be built around victims’ actual needs and concerns, not the UN’s own idea of what they might be.