Community engagement became a formal requirement of planning in Canada via the neighbourhood improvement program of the 1970s.

That program required local governments to work together with residents to rehabilitate neighbourhoods in order to access federal funding. It was created in response to the phenomenon of residents protesting freeways and other unwanted neighbourhood changes. Ensuring neighbourhood input on the provision of services, infrastructure and amenities — schools, street-calming measures, bus stops, parks, shops and meeting places, for example — became core to urban planning.

Fast forward 50 years and federal, provincial and local governments in Canada have flipped the script on this logic. Community engagement in planning at the neighbourhood scale is considered a barrier.

Cities in Western Canada are passing blanket rezoning and district-based planning policies that shut neighbourhoods out of the process. The cities of Edmonton and Calgary are cases in point, with neighbourhood groups in vocal opposition.

The scene in South Vancouver

In Vancouver, the same process is afoot. While the rationale is that the move will improve housing affordability, it threatens to perpetuate disadvantages in neighbourhoods that are growing in population without redevelopment.

As researchers in urban studies and health sciences, we demonstrated this effect through a neighbourhood equity analysis. We examined South Vancouver, a group of six distinct neighbourhoods that account for 15 per cent of Vancouver’s population. In all the ways that public services and infrastructure are funded — from child care to direct social spending and improvements paid via development contributions — these neighbourhoods are not getting their fair share. Eliminating neighbourhood planning prevents them from doing better for themselves.

In June 2023, community justice advocates from the South Vancouver Neighbourhood House (SVNH) brought a motion to Vancouver City Council with a pointed name: “Addressing Historic Inequities by Improving Infrastructure and Access to Services across South Vancouver and Marpole Neighbourhoods.”

In addition to acknowledgement of their needs, the motion sought recognition of the organization’s capabilities to act on these inequities. Neighbours flooded council chambers and the motion passed unanimously. It was an impressive win for SVNH’s first formal political manoeuvre.

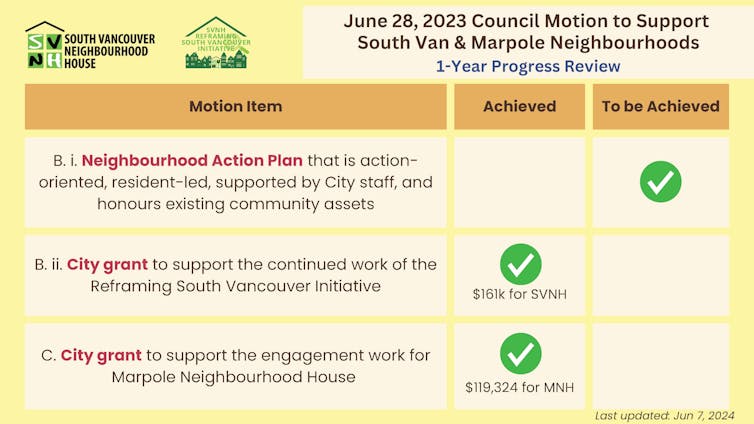

One year later, the report card released by SVNH shows progress. The organization has received an allocation of $161,000 from the city’s Community Services and Other Social Policy Grants budget, which SVNH has used to continue their major initiative, Reframing South Vancouver.

Since fundraising to launch that initiative in 2021, SVNH has engaged more than 2,000 residents, organized neighbourhood advisory committees, documented priorities and consulted with decision-makers, all while strengthening the fabric of the community.

But progress is stalled in certain areas. The motion sought recognition and implementation of SVNH’s efforts as a Neighbourhood Action Plan. The city has resisted.

Shutting out neighbours?

The problem encountered by SVNH is that the City of Vancouver’s Planning Department, once a bastion of neighbourhood participation, has turned on neighbours. CityPlan, Vancouver’s community plan of the 1990s, upheld a mantra of a city of neighbourhoods in which “the neighbourhood is the prime increment for change,” in the words of one of CityPlan’s two co-directors, Larry Beasley, in his 2019 retrospective book Vancouverism.

Vancouver’s new community plan, passed in 2022, will be adopted as the city’s Official Development Plan in 2026. It imagines a future in which all neighbourhoods are equitable, diverse, inclusive, resilient and complete. This much has not changed from the 1990s. What has changed is what this means for individual neighbourhoods.

When the plan lists “our strengths,” specific neighbourhoods aren’t named; instead, “under-utilized neighbourhoods” appear as one of the city’s main challenges.

When it comes to South Vancouver, this turn away from neighbourhood power threatens to take the benefits of their collective work out of their capable hands, leaving South Vancouver residents disadvantaged.

South Vancouver falling behind

Our neighbourhood equity analysis found that South Vancouver is home to about 100,000 people, including the city’s largest share of racialized residents (80 per cent) and its largest share of immigrants (56 per cent). Population growth has been higher in South Vancouver than in most other areas of the city.

The area is home to nearly a quarter of those under 15 in the city, and has experienced a higher rate of growth of seniors than the city overall. Household size is larger (2.7 people per household compared to 2.2 citywide), with many multi-generational households.

Whereas the average household in South Vancouver was middle class in the 1980s, the majority of households now fall behind, with an average median family income of $79,000 compared to $91,000 citywide.

The area is a hilly 20-minute drive from east to west, and more reliant on public transit. This means longer, more difficult commutes.

South Vancouver has also seen less redevelopment than elsewhere in the city. There are few social service hubs: only three community centres, three libraries and one neighbourhood house. One community health centre serves the entire area. South Vancouver also has a shortage of food assets and notably, only three hubs provided free or low-cost food during the COVID-19 pandemic out of 70 such hubs across the city.

At the same time, SVNH performs vital community work. Meaningful programs included delivering food services during the COVID-19 shutdown of most city food banks. The lack of authority to plan hampers SVNH’s ability to land a permanent location for their food hub that residents now rely upon or to chart a path toward food justice.

The Vancouver Plan asserts the “need to set realistic expectations” about neighbourhood identity in the face of growth and change. Taking a lesson in expectations from neighbourhood organizations like SVNH, planning departments should keep in mind that liveable neighbourhoods need the collective capabilities of neighbours, too.

Mimi Rennie, Liza Bautista, Prabhi Deol and Cherry Wong of the South Vancouver Neighbourhood House contributed to this article.