Review: Heaven and Earth in Chinese Art, Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei, Art Gallery of New South Wales.

The exhibition Heaven and Earth in Chinese Art, Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei, is the first major loan to Australia from this repository of what have become the canonical art works of Chinese culture. It deserves to be seen by all those interested in Chinese art, and hopefully will be the precursor for many such loans in the future.

Perhaps it will also prod the National Palace Museum in Beijing to do a major loan exhibition, in the same way that Sydney has already been blessed with major loans from other mainland Chinese provincial museums. The great ecumene of Chinese culture and its artefacts is too broad and its products too interesting and significant to let them stay entrapped within one exclusive political domain or another.

We can view exhibitions in terms of their spectacle, the variously pleasing or unappealing aesthetic qualities of the works displayed, or in terms of an art tendency or cultural world represented by the kinds of works shown. Art works are also markers for a flow in cultural material between different countries, and one can think about why such a work was shown in this country or not, as the case may be.

This Sydney exhibition forms part of a broad spectrum of National Palace Museum Taipei excursions abroad beginning in 1961 with the Smithsonian Museum and including later the Metropolitan Museum of New York.

Ordinary viewers and specialist scholars may quibble about so many masterworks of Chinese art not seen in this exhibition. For instance, paintings from the Northern and Southern Song dynasties now in Taipei, such as Fan Kuan (ca. 950 to ca.1031) Travellers among mountains and streams, will not now be allowed to go overseas because of conservation considerations. The Australian viewer may hunger after such actual works but even in Taipei, many of these have a very restricted display schedule of about a month once every two or three years.

Apart from the question of how works appear or do not, there is the matter of how any given exhibition was generated. The current one was subject of a Loan Agreement in 2018 and is therefore the product of long and complex cultural diplomatic contacts much beyond curatorial decisions.

The works shown are organised in the following categories: Heaven and Earth; Seasons; Places; Landscape; Humanity. They were chosen to introduce works to a broad and often unfamiliar or uneducated audience, for whom explication of fuller art historical meaning could have been daunting.

An opening and very carefully calibrated presentation of calligraphies manages to show without pedagogic introduction the main types of calligraphic form via some well-known examples. These are carefully drawn against various types of production, format and author. Specialists might find it difficult to encounter first the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) piece Four abridged phrases from Detailed Ceremonials, followed by the Song Emperor Huizong (reigned, 1101-25), Poem on peonies in regular script.

Still, what might be called the limpid rigidity of his scripts actually can prepare the untutored viewer for the wider range of graphic forms in the older Song stele rubbing of 18 scripts of Mengying (active after the 900s). This set of mannerisms has long antecedents in China, including the Bound tablets for the shan sacrifice of the Tang Emperor Xuanzong of 725, shown elsewhere in the exhibition.

The visitor can thus in a few paces, and via works some of which are “national treasures”, see much of the historical range of written production and re-production with its attendant graphic sensibility through calligraphy, relief printing, and carving.

There are several art historically significant paintings in the exhibition. One is attributed to Mi Fu (1051-1107) but is given as a 17th century copy after a work by Mi Fu’s son Mi Youren, and carries the encomium of Emperor Qian Long (reg. 1731-1796), a horizontal handscroll Cloudy Mountains with self-written inscription.

The sketchy tonality and brushwork with apparently not much ink contrast, apparently casually, even rather carelessly applied, became one of a core set of styles that was later to define the painting of literati landscape.

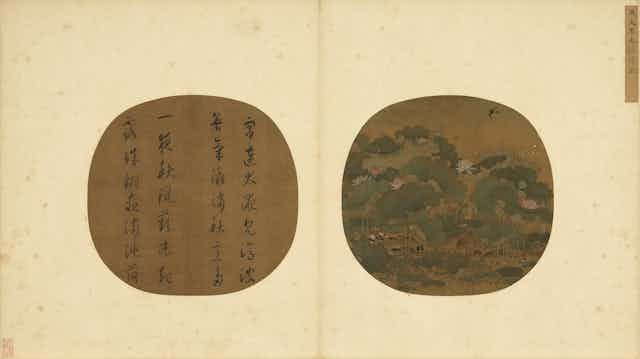

One other type of work here displayed is Southern Sung album paintings. Later research established in many cases that these were done for female members of the imperial court and even, in some cases, by female painters. These albums are very dark in their surviving state and turned flat on their side as here displayed are not easily seen by the viewer.

They are important, such as Taiye Lotus Pond by Feng Dayou (active mid-12th century), Viewing a Waterfall by Xia Gui (act.1180-c1230) and Evening stroll by Lamplight by Ma Lin (c.1195-1264).

These ostensibly highly professional paintings also displayed values of “realistic” drawing sought in the Song academic manner that became the genealogical base for the alternative, non-literati trajectory of ink painting in the late Ming, such as Parting at Jinchang by Tang Yin(1470-1524).

The Song album paintings displayed a poetic visualization of a domestic life which was neither that of the lonely, politically exiled recluse, or the grand, cosmographic, landscape panorama.

In terms of the presentation of paintings in this exhibition, one could get involved over the minutiae of attribution. (Is the Viewing Geese at the Orchid Painting by Qian Xuan (1239-1301) the original work in a series of later historical transmissions or is it in some way a later Ming variation? And the green and blue landscape Viewing the Spring given to Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322) may or may not be by him.)

Exhibitions of paintings seem of necessity to include ceramic and bronze pieces that hint at the domestic decoration of everyday life. These utensils and various kinds of display draw from domestic celebration of guests, formal ancestral ritual, and court ceremonial life.

Unfortunately these linkages require some commitment to discern in the rather haphazard collection of ceramics and bronze displayed here, despite the presence of rare ceramic pieces that are unquestionably major art historical monuments.

These include the monochrome Song Celadon warming bowl in the shape of a lotus blossom (960-1279) or the Jin-Yuan Dish with sky-blue glaze and purple splashes (ca 115-1368). These are very splendid but into what kind and period of imperial, scholarly, or plebeian taste they may fit is quite unclear.

The relationship with later cloisonné enamels of the 18th century also shown remains a bit too close to a display of accumulated consumer treasure for appreciative viewing.

Indeed the problem of all introductory exhibitions, (even when referring to a canonical collection), is that the supposed status of works may provide the all-fulfilling meaning for the viewer rather than access via cosmographic, historical, conceptual or other kinds of interpretation. These will require much more thorough expostulation, and narrower selection of works by type, series, or period.

Display spectacle is what actual museums now require before all else. With a little insight and patience, and detailed if occasionally circumlocutory catalogue notes, this exhibition has well provided it.

Heaven and Earth in Chinese Art, Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei is at the AGNSW until May 5.