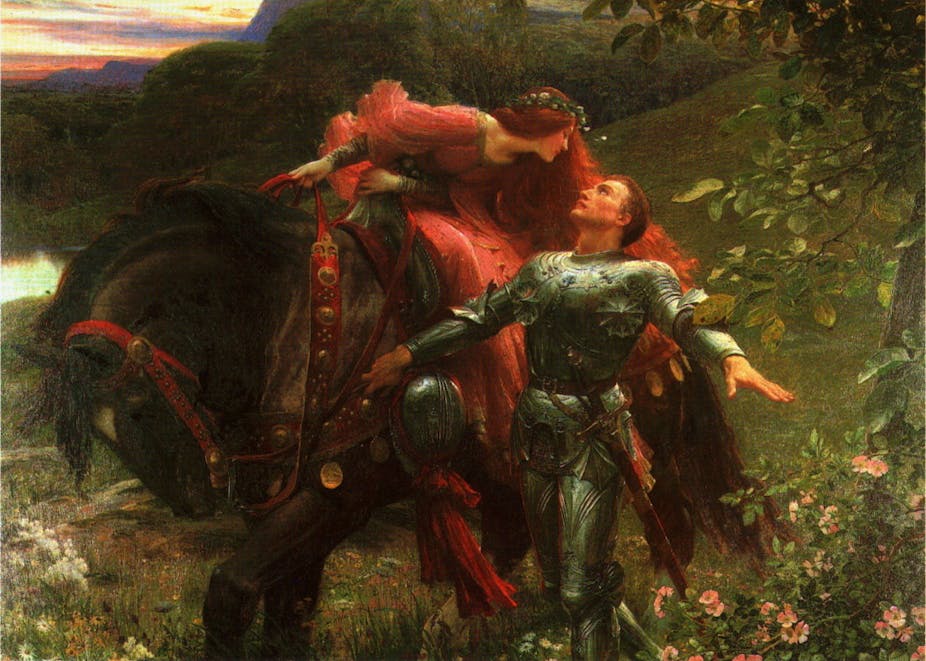

Any prize for the most enigmatic character in English poetry would probably go to the truant knight in John Keats’s much-loved 1819 ballad La Belle Dame Sans Merci. All the desolate knight is able to tell us with any clarity is that a beautiful lady whom he met “in the meads” stole his heart before cruelly abandoning him. Even that account is open to interpretation, since we never hear La Belle Dame’s own version of events.

200 years on, we’re no closer to agreeing what the highly symbolic poem might mean, let alone to tracing the knight back to an actual historical figure. But a new discovery from the archives of the British Museum might be about to change that.

At some level, the ballad probably registers Keats’s own sense of doom over his relationship with fiancée Fanny Brawne. Illness and financial uncertainty were proving barriers to consummation and marriage. Beyond that lies only guesswork. Many have grown used to thinking about the famous romantic poem as the purest example of spontaneous inspiration. It even appears without preamble in one of Keats’s letters, increasing the impression that it arrived out of nowhere, dictated by the muse.

But that’s not how Keats usually worked. Many of his best-known poems take vital cues from the physical objects he saw around him. Think of the “heifer lowing at the skies” in Ode on a Grecian Urn. The mooing cameo owes its existence to a sculpted cow on the Parthenon frieze that Keats saw in the British Museum. Similarly, the anguished Titans in The Fall of Hyperion were likely inspired by the grimacing statues depicting manic and melancholic madness that adorned the gateposts of Bethlem Hospital (known to London and the world as Bedlam). Keats knew them only too well as a young boy growing up in Moorfields.

Stoney origins

In the run-up to the ballad’s composition Keats was in Chichester to finish his medieval romance The Eve of St Agnes. During his stay he visited Chichester Cathedral, where a very striking knight-at-arms was housed. Millions of readers know it today from the perennial favourite Philip Larkin poem, An Arundel Tomb. Larkin visited in 1956, when the brawny alabaster effigy of a chain-mailed Richard FitzAlan, tenth Earl of Arundel, lying hand-in-hand beside his own Belle Dame, Eleanor of Lancaster, inspired one of the poet’s most quoted lines: “What will survive of us is love”.

It’s never occurred to anyone that Keats’s imagination might also have been set racing by the stone avatars of the Arundels, because the serene gleaming effigies don’t seem to have much in common with Keats’s haggard knight. However, intriguing visual evidence in the form of two little-known sketches in the British Museum may hold the key to the mystery.

Larkin viewed the alabaster effigies after their Victorian restoration. In 1843, the extensively damaged statues of Richard and Eleanor, which had been torn apart to save space, were reunited, presenting the sentimental tableau of conjugal affection that moved Larkin to an uncharacteristic moment of (albeit cagey) optimism about love.

When Keats visited the cathedral in January 1819, things were very different. The recumbent knight was grimy and badly weathered from having lain for a century outside in the elements (“sadly mutilated”, in the words of the 1844 Antiquarian and Architectural Yearbook). He was heavily graffiti-ed with “dates and initials of the mischievous and ignorant”, the earliest from 1604 – and he was missing an arm. His lady lay not beside him but stowed a few metres away at his feet, separated by a pillar. He was the very model of woe-begone.

The effigies also retained faint traces of medieval paint, including “small quantities of crimson”, which perhaps throw light on the “fading rose” of the feverish knight’s complexion in Keats’s ballad.

After visiting Chichester, Keats moved on to nearby Bedhampton, where he stayed with prosperous millers John and Letitia Snook. When illness allowed him to venture beyond the garden gate, he would have found a granary, a sedgy lake, and in the centre of the village Bidbury Mead. All feature in La Belle Dame Sans Merci, from the withered vegetation around the lake, and the meads where the knight encounters the lady, to the “squirrel’s granary”.

Visions of love

Could Chichester Cathedral’s famous effigies have inspired not just one but two well-known – though very different – visions of love? Larkin’s holds out the possibility that love conquers all. Keats’s looks towards the abyss. It’s even possible that Keats wasn’t above a dark pun at the effigy’s expense. Could it really be a coincidence that Keats came up with the idea of a “knight-at-arms” after seeing the cathedral’s wounded knight-without-arms? Whatever the case, the emasculated effigy of Richard FitzAlan would have resonated with Keats’s own precarious sense of virility.

Even the ballad’s birds who do not sing may have their origins in a real absence. The damp, wetland habitat around Bedhampton’s lakes made a perfect home for sedge warblers. These chattery passerines would have been wintering in sub-Saharan Africa when Keats arrived in the village. In other words, we may now know the sound of one of the most famous of literary silences.

Poems can rarely be chased back to a single source of inspiration. Even ekphrastic poems, which deliberately set out to describe physical objects, are hardly ever one-to-one engagements with their subjects. The poetic imagination simply doesn’t work like that. That’s especially true of La Belle Dame Sans Merci, a particularly rich example of writing that resists explanation. Nevertheless, Chichester Cathedral’s armless knight, usually associated with Larkin’s An Arundel Tomb, deserves to be recognised as part of the heady mix that produced a lover’s complaint which has haunted generations of readers.