“You can’t buy the will to fight.” This comment by James Clapper, the former director of National Intelligence of the United States, is an astute remark on the recent collapse of the Afghan government and military.

I would add, however, that perhaps you can build the confidence to fight.

The U.S. is learning for the second time in half a century that the will to fight trumps western military training, technological superiority and money. The Taliban possessed the will to fight and little else. The Afghan National Security Forces had it all but lacked the will to fight.

While the Afghan military and police fought hard and sustained perhaps 66,000 fatalities in a long campaign against the Taliban, they seem to have given up the moment a few thousand U.S. and NATO ground forces and civilian support contractors withdrew.

Retired Gen. David Petraeus, former International Security Assistance Force commander, has said that both the announcement of and the act of withdrawal was a psychological blow to the Afghan forces that led to a rational choice on their part to stop fighting. The Afghans lost the will to fight when the West no longer had their backs.

Saigon comparisons

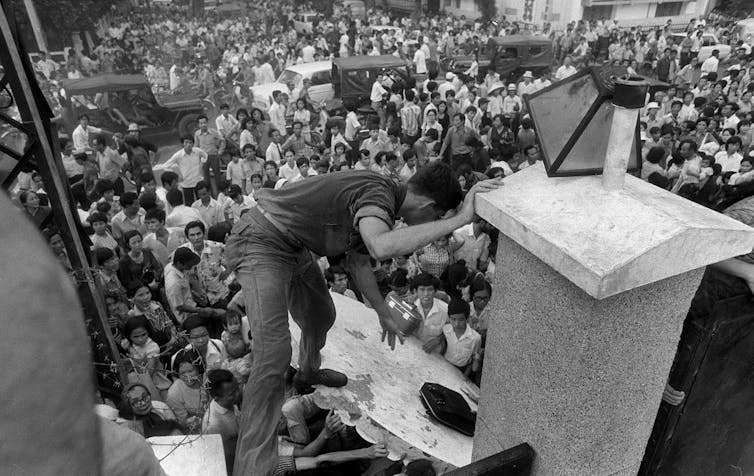

The media are likening the fiasco unfolding in Kabul to the humiliating American abandonment of their embassy in Saigon in April 1975.

In both Saigon then and Kabul today we saw images of a chaotic evacuation of Americans and thousands of locals who worked with them trying desperately to board U.S. military aircraft to escape imprisonment, torture or death. And in both cases, American-trained and well-equipped militaries lost the will to fight when U.S. forces departed.

These and other similarities between these two conflicts are striking. But there are also some big differences.

By the late 1960s, the Vietnam War was the most divisive issue in America, central to both the 1968 and 1972 presidential elections. It was the reason President Lyndon B. Johnson did not seek re-election.

By the early 1970s, American involvement in Vietnam was no longer sustainable for any U.S. administration. With a partially conscripted force, 58,000 dead and 153,000 wounded Americans, the U.S. public would no longer tolerate involvement in Vietnam.

Afghanistan contrasts

This is in sharp contrast to American involvement in Afghanistan today. While polls suggest 60 per cent to 70 per cent of Americans favoured U.S. troop withdrawal from Afghanistan, the Afghan war was not a major issue in the last two presidential elections.

Twenty years after 9/11, with about 2,500 American fatalities in Afghanistan — less than five per cent of the total in Vietnam — the Afghan war has not been top of mind for most Americans for years. Afghanistan has been both America’s longest war and America’s forgotten war.

While former U.S. president Richard Nixon had no choice but to pull America out of Vietnam, President Joe Biden had room to manoeuvre on Afghanistan, yet he chose to follow his predecessors’ path and end America’s military presence there.

Part of the rationale for Biden’s withdrawal decision was based on his assertion that “our mission in Afghanistan was never supposed to be about nation-building.” On one level the president’s claim is accurate, at another it’s misleading.

Eliminating al-Qaida

The initial U.S.-led coalition that invaded Afghanistan had the narrow aim of eliminating al-Qaida operatives and toppling the Taliban regime that was harbouring them. Beyond that, the George W. Bush administration did not have much of a plan for Afghanistan, and was soon courting NATO allies to do the nation-building part.

In January 2003, I was chief of staff to Canadian Defence Minister John McCallum and we attended a meeting in the Pentagon with U.S. Defence Secretary Donald Rumsfeld. During that meeting, Rumsfeld made the point that reconstruction, stabilization and nation-building in Afghanistan — while badly needed — were tasks best suited to countries like Canada and a few European countries, not the United States.

Nevertheless, while U.S. operations in Afghanistan were not focused on nation-building in the beginning, by 2019, Washington had spent US$87 billion training and equipping the Afghan military and police forces; US$24 billion on economic development and US$30 billion on reconstruction programs, according to the New York Times.

Destined to fail?

Perhaps, as others have argued, nation-building in Afghanistan was destined to fail, as it did in South Vietnam half a century before, even though it’s been core to American involvement in Afghanistan for at least 15 years.

Read more: Why did a military superpower fail in Afghanistan?

That said, the American and NATO military presence in Afghanistan did seem to be working, at least in terms of giving confidence to the Afghan forces to continue their fight against the insurgents, though they had been losing ground to the Taliban for years.

The pullout of those remaining U.S. forces appears to have gutted that confidence overnight. It could prove to be the biggest error Washington has made during 20 years in Afghanistan.

The Vietnam War was the defining issue for Biden’s generation. His decision to withdraw American forces from Afghanistan — coupled with a botched withdrawal leading to humiliating images for America and a looming humanitarian crisis for Afghans — could be the defining act of his presidency.