What has shocked the cricketing world so profoundly about the recent ball-tampering scandal is not the actual physical act of Australian test batsman Cameron Bancroft illegally altering the cricket ball to make it easier for his team’s bowlers. That’s a relatively low-level infringement of the rules. It was that it appeared he had conspired with his captain and vice-captain to gain an unfair advantage. This was considered an egregious breach – not only of the laws, but of the very spirit of cricket itself.

It’s this nebulous and shifting idea – the spirit of cricket – that cricket lovers believe sets the game apart from – and above – all other competitive sports.

In 1801, the year before his death, antiquarian and literary researcher Joseph Strutt made the claim in his book, The sports and pastimes of the people of England, that “in order to form a just estimate of any particular people it is absolutely necessary to investigate the sports and pastimes most prevalent amongst them”.

This is a bold assertion by an author wishing to persuade others to take serious the study of what, to many, seemed a frivolous pursuit. But more than 200 years later, the connection between sport and the moral and spiritual standing of those who play it remains strong. And of all sports, cricket has developed with the idea of fair play at its heart.

Going beyond “the umpire is always right”, the practice of “walking” – batsmen not waiting for the umpire to adjudge them as out – for example, or a fielder admitting when they had not taken a catch cleanly, took the idea of honourable behaviour beyond that of other sports.

The vernacular of cricketing morality is common to the English language - “keeping a straight bat”, “to have a good innings”, “to be on a sticky wicket” and “to do it off one’s own bat” are sayings laced with moral intent.

In this way, fair play became a central characteristic of cricket and underpinning its global appeal, despite what many may consider its aristocratic, colonial and misogynistic past. This enduring association points to the idea that what is central about cricketing fair play transcends external inequalities of class, race, sex, and money and is more about its inherent qualities – about how the game is to be played in terms of respect for its laws and the spirit of the game.

Toffs and gamblers

Fair play in cricket is born out of the interaction between aristocratic landowners and their artisan labourers in the south-east of England toward the end of the 18th century, and their shared love of gambling. At this relatively prosperous time, opportunities for recreation increased significantly and as a result informal bat and ball games that had come and gone in various guises over the centuries acquired critical mass.

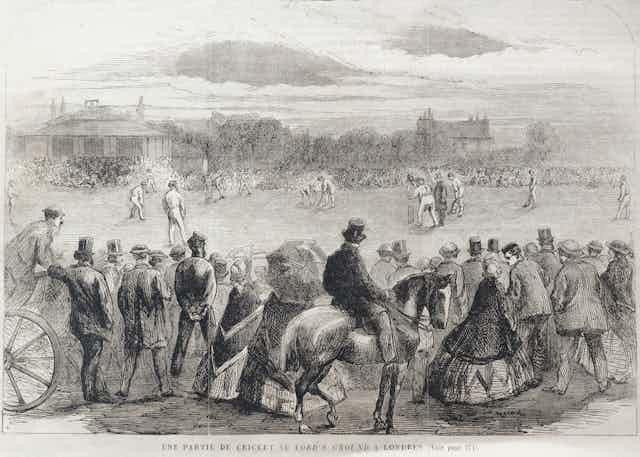

It is at this time we see the game being played by more people, more often and in a more structured way to the extent that it provided a new opportunity for gambling – a competitor to other established forms of sport betting such as horse racing, hare coursing and the rest. Gambling was the passion of everyone – for landowners giving patronage to their teams in order to bet among themselves and the artisan labourers either playing or watching.

The popularity of gambling and the popularity of cricket then gave rise to the need for consistency in terms of codified laws, so that there would be clarity for wagers. Papers were drawn up for most stake-money matches that were essentially “play-or-pay” contracts between the contending parties. Fairness in cricket therefore first emerges as a necessary condition for the widespread promotion of gambling.

Gents and players

Next came the inevitable struggle for control as to who should write the laws and what they should look like. It was inevitable that the supreme authority for the laws of the cricket would come from aristocratic players and supporters of the game. The initiative was seized by the MCC, a club which emerged in 1787 out of the White Conduit Club. Very quickly, the MCC was recognised as the sole authority for drafting cricket’s laws and for all subsequent changes.

This shift now severed the collaboration between aristocrats and their artisan labourers. It also meant a geographical shift from rural countryside to urban London. The change of scene and people resulted in changes in perspective, of attitude and of meaning towards the game. Among the new aristocratic leadership were the “fair play” lobby such as George Finch, 9th Earl of Winchilsea who believed that gambling had no place in sport. Gamblers, like professionals, pursued any means to ensure victory – an attitude that ran contrary to the view that, while winning was the point of cricket, the manner in which victory was achieved was more important. The amateur ethos that eventually dominated British sport thus sanitised a large part of cricket of its Georgian gambling associations.

The final piece to seal the place of cricketing fair play as an enduring national morality was the popularisation of sport in English public schools. In this environment – cleansed (at least for the most part) of external vice from the outside world – the idea of fair play advanced relatively unchecked. Driven on by evangelical advocates such as Rugby School’s Thomas Arnold, the stage was set for the cultivation of an ideal that, to this day, is held to be the sport’s central tenet.

The recent ball-tampering affair wasn’t the first scandal to envelop cricket – far from it. In recent years match fixing has become a scourge in the sport and, in 2011, three Pakistani players were jailed for taking money as part of a fraudulent betting scam. Australia’s ball-tampering shame at least has the virtue of not actually being a criminal offence. But the enduring irony of these sorry episodes is that cricket – a sport whose rules were developed in the main to assist what is considered to the vice of gambling – should have gone on to become the paragon of fairness.