The history of how a new city of Pompeii was built in the 19th century is little known, but a new exhibit reveals its story.

The exhibition, held in the Catholic shrine of the Blessed Virgin of the Rosary of Pompeii, sheds new light on the relationship between science and religion in the late 19th century. The exhibition tells the story of the Meteorological-Geodynamic-Volcanological Observatory that was set up at the shrine in 1890 to monitor the activity of Mount Vesuvius.

This Pompeii isn’t the famous ancient Greco-Roman city, which was destroyed by an eruption of Vesuvius in AD79, but rather the modern city down the road from the excavations. The city centres around the huge Catholic shrine, which was founded in the 1870s by an energetic lawyer called Bartolo Longo, on a plot of land next to the ancient Roman amphitheatre.

During his lifetime, Longo built a “new Pompeii” which attracted pilgrims and visitors from all over Italy and beyond. As well as the magnificent church with its treasured painting of Our Lady of Pompeii, the city was home to several charitable institutions and pioneering urban projects, including an orphanage for girls, a residential home for the sons of prisoners, an industrial-scale printing press – and the observatory.

The new exhibition is displayed in a room with high ceilings in the shrine archives. A neat display of antique photographs, documents and original scientific instruments tells the story of this important but little-known episode in the history of science.

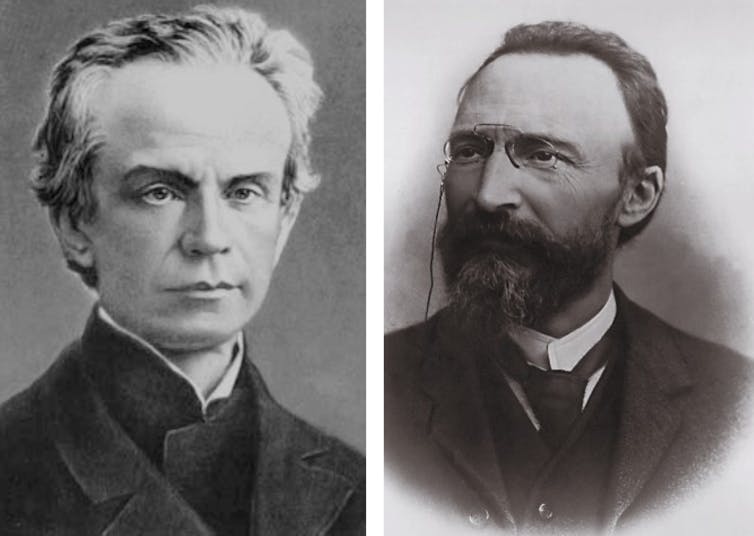

The development of the new city all started with a miracle. In 1886, Francesco Denza (a Barnabite priest and eminent astronomer, who was the first director of the Vatican’s Observatory) recovered from paralysis after praying to Our Lady of Pompeii.

Denza came to Pompeii to give thanks for this healing miracle, and asked what he could do for the shrine in return. Longo proposed setting up an observatory on site, with Denza as director. A tower was constructed above the girls’ orphanage, and filled with state-of-the-art modern instruments.

Longo then organised a grand festival of science to coincide with the observatory’s inauguration on the Feast of the Ascension on May 15 1890. Reports of the event suggest 20,000 people attended. They listened to speeches in praise of the observatory and the broader union of the science, faith and charity that it represented.

Longo’s own speech contrasted the new Christian Pompeii with the ancient Greco-Roman city next door. It pointed to the bloody slaughter that took place in its amphitheatre, where brutal gladiatorial combats and staged animal hunts had been the favourite forms of entertainment in the ancient city.

The new observatory’s significance

The new Pompeii observatory monitored the activity of Mount Vesuvius, keeping track of seismic movements and meteorological changes. Its regular data bulletins – which were dispatched to other observatories around Italy, as well as to individual scientists and shrine benefactors – now constitute a valuable record of geological events in this unique volcanic terrain.

For instance, the bulletin for September 1 1890 records how: “The lava at the base of the main channel of Vesuvius has formed into a horseshoe shape: on the south-south-eastern side the lava is flowing more abundantly … The crater is emitting occasional flares and a calm jet of projected materials.”

Longo saw the observatory as proof of how religion and science could exist in happy union – contrary to the widespread conviction that “science and faith must of necessity be in eternal disagreement” (to cite from his inaugural speech).

That is the driving message of the shrine’s current exhibition as well. I spoke with the curator, Salvatore Sorrentino (himself both a mathematician and member of the Pompeian clergy). He explained that the observatory itself was born from a scientist’s act of faith, that is, Denza’s prayers to God, through the intercession of the Blessed Virgin.

Sorrentino also drew a comparison with the work of the great Pisan scientist Galileo Galilei (1564-1642), who saw his own experimental methods as a means of asking questions of God, and of discovering the footprint of the creator in the physical world.

The observatory is a landmark in the history of science, that changed the way that the land around Pompeii was understood at the end of the 19th century. Yet at Pompeii, as elsewhere, there was still room for older religious understandings.

An inscription chiselled into the shrine façade commemorates how Pompeii was delivered from the major eruption of April 1906. The inscription records “for posterity” how the painting of Our Lady was taken out of the church during the eruption, and carried in a procession “in view of the fiery peak”.

The surrounding towns “were terrified by the darkness and ruins”, but at Pompeii “the sky became calm, and all souls were reassured”.

The news bulletin published by the shrine narrates how, by the end of this violent eruption, the new Pompeii had received only the gentlest sprinkling of ashes.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.