In many of today’s debates on the world’s great challenges, one question that keeps getting asked – most prominently by the climate change activist Greta Thunberg – is “why don’t politicians listen to the experts?” Why, for example, don’t governments listen to the recommendations of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and take the necessary action to reduce global warming?

While more expertise does sound like a good solution, it is more complicated than that – for two main reasons. First, experts can bring in crucial information and know-how, but politicians also need to cast judgements about, say, fairness and equality. Politicians can listen to the scientists, and agree that climate change is real, but their opinions about who is responsible and where to make changes may still diverge.

Second, who counts as an expert is not obvious. Often the selection is politically motivated – and once experts are selected, it’s unclear how much power they should have over policies. This means the way politicians use expertise can underestimate or even overlook important questions of legitimacy, and it’s far from an easy add-on to democracy.

In my ongoing doctoral research, I’m exploring how ideas about expert politics proliferated in the 19th century and evolved into a deeper “expert mentality”. This mentality was built around an urge for applying scientific method to all aspects of social and political life for the purposes of progress, an urge in common with imperialism, and most ideologies at the time.

Its proponents hoped to dissolve political disagreement by rendering political problems strictly technical. This hope was as attractive then as it is today – a promise that we might be able to overcome partisanship and replace the politics of belief with a politics of facts.

Birth of a science of politics

In the early 19th century, political theorists and practitioners (particularly in France, Britain and Germany) formulated ideas about what they came to call “political science” – a discipline that would somehow apply the principles of scientific method to the realm of politics.

The puzzle was that politics is often made up of hard-to-grasp phenomena – phenomena that can be observed, but don’t always look the same. Principles like good and bad, fair and unfair, equal and unequal all depend on assumptions, contexts and perspective. So too do actions, whether they are planned and rational, or spontaneous and irrational. The goal was to devise a scientific method that would allow for the observation and examination of such fuzzy concepts, and create “order” from “chaos.”

Determined to tackle this, 19th century political theorists such as John Stuart Mill, philosophers such as Auguste Comte, and statisticians such as Karl Pearson developed increasingly sophisticated methods that sought to distinguish truth from falsehood and fact from belief. But the problem they tried to address remained: politics was still replete with manipulation, partisanship and belief. The move to fact-based politics was far from straightforward.

The making of experts

As the science of politics became popular across Europe, alongside the rise of capitalism and empire, a new mentality emerged. Keen reformers opened schools that would train technical specialists; created international organisations; and promoted the use of expert committees. One of the most widely read of these reformers was Henri de Saint-Simon, who not only strongly influenced Comte’s notion of “positive science,” but also advocated government by an expert elite.

By the late 19th century, an expert mode for doing politics had emerged: the idea that the more specialist knowledge we gather, the better we are equipped to tackle national and international challenges.

Yet from the start, this idea was far from politically neutral. Big technological projects at the time relied on specialist technical knowledge – but they were political and imperial projects first and foremost, looking to spread “civilisation” through technical progress and to extend imperial control.

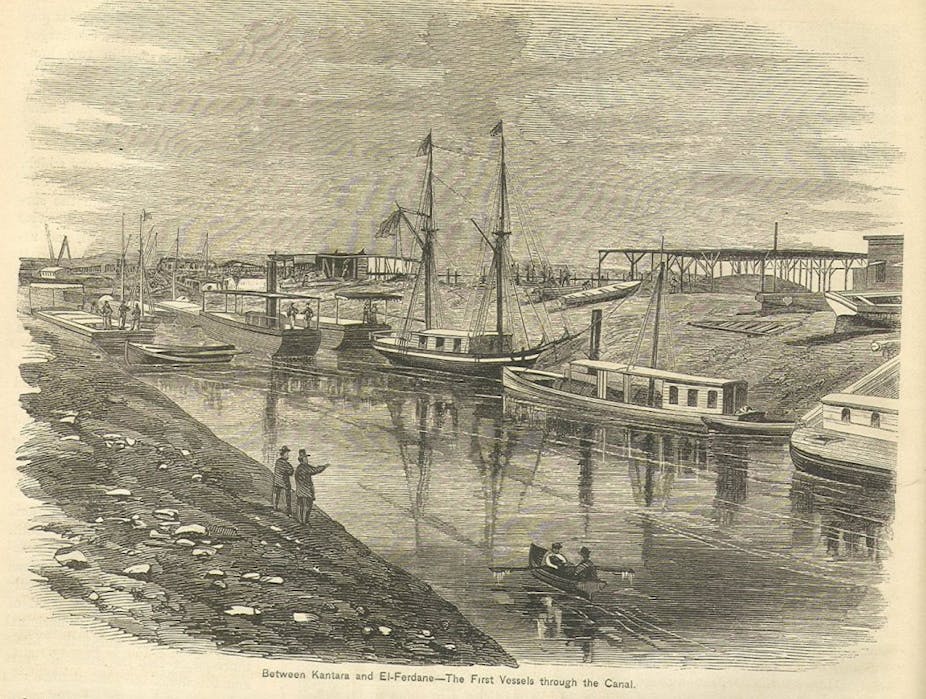

The first transatlantic telegraph cable, completed in 1866, was an Anglo-American project with obvious benefits for speeding up the command structure of the British Empire. Upon the opening of the Suez canal, completed by a French company in 1869 and acquired by the British in 1875, a British contemporary characterised it as “our highway to India.”

In these cases, expertise was brought in to assess the technical feasibility of laying a cable or excavating a canal – but who counted as an expert, and which experts politicians would listen to, were political questions. Often “technical feasibility” was taken as sufficient justification for projects that followed deeply political motivations. The Suez canal is a case in point: once an 1856 scientific commission had agreed the project was feasible, it was built as a private enterprise that exploited Egyptian labour and strengthened European imperial transport routes.

There are various explanations for these projects, and imperial reach certainly informed the rationales for building infrastructure in colonies and protectorates. But the role of expert authority and the supposed depoliticisation it brought about is crucial here, not least because it has survived to the present day.

The technical point of view

With the rise of using technical expertise to address complex political questions in the mid to late 19th century, politics became accessible not only to kings and courtiers, but to trained professionals as well – and with them, a new way of looking at and understanding politics took hold. The expectation was that, thanks to the involvement of technical experts in political decision making, politics would get “closer to the facts” and therefore better.

My ongoing research suggests that one effect of the introduction of expertise into politics is that technical experts can more easily claim to stand outside of politics. It renders politics a set of technical problems that can be solved with technical solutions. Moral problems disappear from view. But history shows that expertise is not something we can simply insert into politics in order to solve its problems.

After knowledge still comes judgement, which is always inherently political. Technical expertise can show that something is feasible, but not whether it is justified.