Lady Gaga’s performance of Til it happens to you at the 2016 Academy Awards drew worldwide attention to sexual violence, and specifically the recent increase in sexual assault on American university campuses.

It resonated elsewhere in the world, too. Stellenbosch University in South Africa has set up a task team to “investigate issues around gender violence” on its campus. About 50km away, students at the University of Cape Town organised a campaign to draw attention to sexual violence and rape culture on their campus. A similar campaign has also been launched at Rhodes University, in the country’s Eastern Cape province.

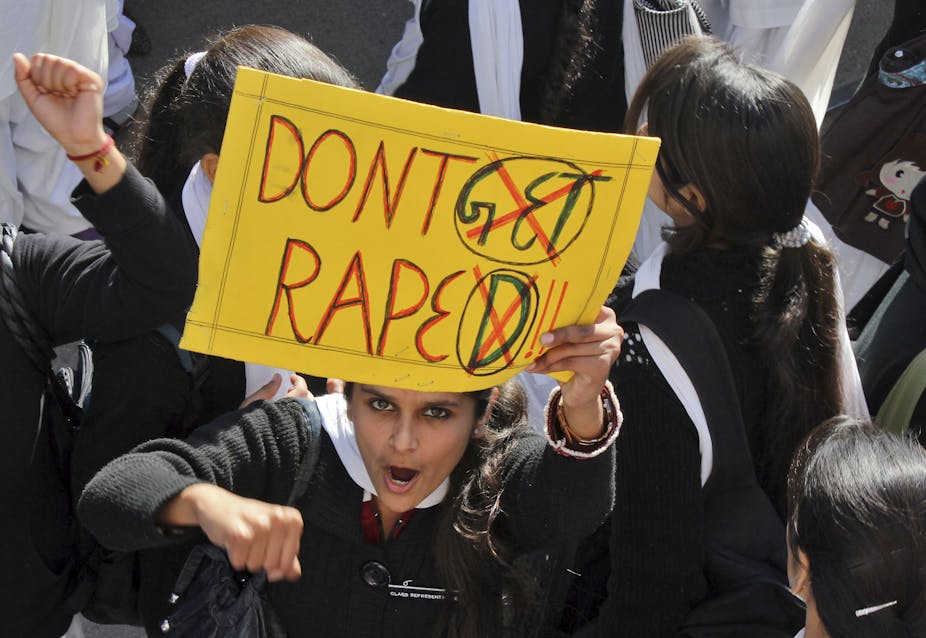

These incidents are further evidence that “rape culture” is a reality in South Africa. The term was coined in the 1970s and refers to the pervasive ideology that supports or excuses sexual assault. In this culture, it is primarily women who experience “a continuum of threatened violence” that ranges from sexist remarks to unwanted sexual touching – and to rape itself.

University campuses are prime locations for rape culture. In the 1980s Mary Koss, an expert on gender-based violence, did a seminal study at 32 university campuses in the US. She found that university campuses are the perfect site for “sexual aggression and victimisation” of women because they are closed institutions, much like the military and prisons. People live, study, work and play in the same environment. A university campus is a closed environment with particular norms and practices to which its community is constantly exposed. Within such settings it is very hard to counter whatever is considered normal and acceptable.

South Africa faces a particularly pernicious problem given the country’s high levels of violence against women. Universities can take a decisive step by addressing the widespread prevalence of rape culture on their campuses, drawing from the experience of others, particularly in the US.

The broader South African context

South Africa has high rates of rape, though these are incredibly underreported. The headlines are sickeningly common: the atrocious treatment of a four-year-old rape victim, or the gang rape of a 16-year-old while her mother is forced to listen. Every day there’s a report about sexual violence somewhere in the country.

But rape culture is about far more than rape. Rape culture is created and enabled by patriarchy, which empowers men at the expense of women. It supports a hegemonic, idealised version of masculinity that does not easily allow for alternative expressions of being a man. This is why not only women and girls are victims of rape culture – men and boys are sometimes, too.

Discussing rape culture involves talking about the societal attitudes regarding sexuality and gender that normalises sexual abuse. Society normalises sexually violent acts in various ways. Through jokes, song lyrics, advertising billboards and bestselling novels, among others, a culture is created where sexual violence becomes permissible.

Not all sexist societies manifest high levels of violence against women. But research has showed that rape in South Africa is “deeply embedded in ideas of manhood”. Researchers and gender activists have also argued that the violent repression of apartheid has played a role in cementing rape culture.

Rape culture in South Africa manifests in the highest levels of government: President Jacob Zuma accusing women of complaining about harassment too quickly, or stating that single women are a problem in society. It’s also revealed in the way elected male leaders respond to their female counterparts. When the female then-leader of the opposition Democratic Alliance and premier of the Western Cape province installed an all-male provincial cabinet, they were called her “boyfriends and concubines”. Another woman opposition politician was dismissed as a “tea girl”, and her dress and hairstyle were criticised in the country’s parliament.

South African universities exist within this context. This arguably makes it even more likely for rape culture to pervade their campuses. All of this is not to suggest, though, that universities can do nothing about it.

Universities can do a great deal

At other universities, especially in the US, various interventions have been launched to address rape culture. Some launch semester-long rape education courses with the aim of developing rape consciousness among students. Some focus on mobilising bystanders to address rape culture. At some universities, faculty members have become involved as researchers, teachers, advocates or policy reformers.

South Africa’s universities can draw from this existing hard work in addressing their own rape cultures. It will have to be contextualised, though, especially keeping in mind how violent South African society is.

Universities are also in the fortunate position of being educational centres. This means they are well placed to educate students in a myriad ways about identifying and tackling rape culture. An enclosed university environment also arguably makes for an easier setting in which to challenge the broader issue of rape culture – compared to, say, South Africa at large. But addressing rape culture will require long-term prioritising and commitment from university management. This is something that has been lacking on many, if not most, campuses.

A cautionary note, though: while people are rightly shocked about rape at a university, institutions should be careful that their interventions are about addressing this rather than about restoring their own reputations. It has been sad to realise that there is not the same outcry when rape culture is seen in action in South Africa at large. Why are so many people only dismayed when these things happen at a prestigious university?