Earlier this year, musicologist Joe Bennett took a sample of the top 200 Spotify streams from the Christmas week of 2016 and dissected those that were Christmas-related.

The results, analysed according to parameters such as beats per minute, key signature and lyrical content, were passed to professional songwriters with a pedigree of hits for major artists to produce an “ultimate” Christmas song. The result is rather effective, even for unbelievers.

Aptly enough, that project was commissioned by a chain of shopping centres. But while it distinguishes between lyrical themes, it primarily illuminates the aesthetic dead-centre of the Christmas pop song.

From commerce to campaigns – political Christmas songs

The concept of the “Christmas song” is rife with political contradictions. It marks a day to put aside division and commerce, and yet is aimed squarely at that most blatantly commercial and competitive institution, the pop charts.

There’s a broad umbrella of musical and lyrical tropes that – pardon the pun – rings bells for listeners in constituting a “Christmas song”. The machine-tooled nature of the archetypal Christmas pop song is such a recognisable format, in fact, that it’s been opened up to a hybrid of data analysis and songwriting, as Bennett’s work illustrates.

Other researchers have sought to bring a broader typology to the service of unpicking the ideological resonance behind Christmas songs.

The musicologist Freya Jarman, for instance, uses a framework of overlapping concepts linked to Christmas, including the “traditional/religious” (such as Mistletoe and Wine), “nostalgia” (White Christmas), “romance” (Last Christmas) or “parties/friends” (I Wish it Could be Christmas Every Day).

The last of Jarman’s categories though – “good will to all men” – most starkly highlights the complexities around commercial acumen and the political potential of Christmas music.

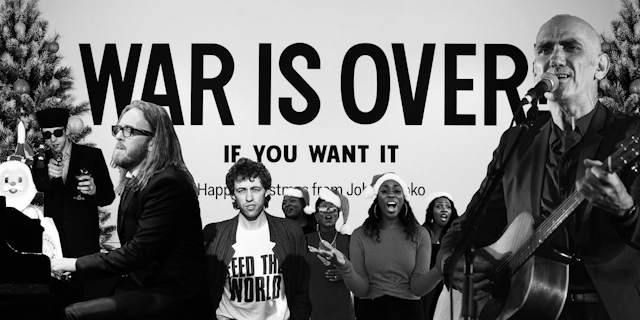

In the broader canon of “political” pop songs, many of the most well known are, in fact, Christmas songs rather than more overt “protest” songs – a political message smuggled in among the sleigh-bells. John Lennon’s Merry Christmas, War is Over is one example, another being Jona Lewie’s Stop the Cavalry, a universal soldier’s lament.

Other Christmas songs, notably Do They Know It’s Christmas, have involved direct political lobbying, such as when Bob Geldof tried to get the government to waive taxes on the single itself. This arguably became a more powerful intervention than other more obviously “political” songs – forcing the government to take a position on the tax arrangements around charity singles.

Such tensions around commerce and authenticity in popular music become especially marked around Christmas, with the charts a key battleground.

When Rage Against the Machine’s Killing in the Name Of became Britain’s Christmas Number 1 in 2009, it was the result of social media campaigning against the domination of X Factor releases as seasonal chart toppers. The song’s broad political message was deployed in the specific context of a longstanding debate within popular music consumption.

This method leaked from commentary on popular music’s internal politics into broader political discourse. Ding Dong, The Witch Is Dead was pushed up the charts by social media after Margaret Thatcher died in 2013 and, latterly, the similar success of a protest mash-up accusing UK Prime Minister Theresa May of being a “Liar Liar” caused headaches for broadcasters regarding election regulations.

Striking a balance

But while the underlying politics of commercialism and community have now extended into the techniques of political messaging the rest of the year round, there are still attempts to strike a balance.

There’s a raft of Christmas songs that circumvent, without fully avoiding, the Yuletide by taking a sideways (or critical) view of it. These allow ambivalent listeners to participate in the festivities while maintaining their sense of critical distance from the more traditional trappings.

Fairytale of New York is an obvious example here. Where the “traditional” Christmas song is about Christmas, it’s about a love story gone awry, with Christmas as the backdrop. This allows sceptics to buy into the aesthetic, and even the sentiment, while holding firm their anti-Christmas credentials.

Others look at the contradictions head-on. Tim Minchin’s White Wine in the Sun uses the Australian December sunshine as a pivot to focus on family, taking a swipe at commerce – “selling Playstations and beer” – while embracing the sentimentality. Addressing the social context of Christmas is another means of tackling the broader, implicit, politics of class.

More universal ‘human’ Christmas messages

Family, fraught relationships and exclusion can make for a more potent, perhaps realistic, Christmas story than snowflakes and Santa.

In The Kinks’ caustic Father Christmas the narrator, a department store Santa, is mugged by a group of youths demanding practical help.

Give us some money … Give my daddy a job ‘cause he needs on".

Paul Kelly’s How to Make Gravy, an isolated and fractious address from a prison cell, packs its emotional punch through mundane details and implied backstory. The story here is both personal and, through that prism, national.

Eschewing the standard Christmas musical and lyrical devices entirely, How to Make Gravy is at the opposite end of the spectrum to the typical tinsel-draped fare, and buries its politics in the personal. Yet it’s still become a Christmas classic.

The search for authenticity and political punch

From outright celebration, through charity to explicit political salvos, there are many ways to musically address the pleasures and strains of the season. Aesthetic tropes – the musical bells and baubles – notwithstanding, the form is actually very broad and embraces a range of genres.

The “ideal” Christmas song in the sense of commercial pop is also open to subversion. Beyond this, there’s a strong draw among some sections of the public towards more cynical, or at least ambivalent, takes on the traditional Christmas customs - even if these often end up adhering to what are ultimately similar sentiments.

As in Dickens’ immortal story of Scrooge in A Christmas Carol, there’s room, it seems, for the humbug to carry the day without ruining it.