In the penultimate episode of Twin Peaks (1990-1991), “I’ll see you again in 25 years” were the words spoken backwards by Laura Palmer (Sheryl Lee) to FBI Special Agent Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan), the detective who had spent more than a season investigating her death.

Following Laura’s promise to Cooper she assumes the frozen pose of a statue before disappearing entirely from view. For those who had watched Twin Peaks during its initial run, this was nothing new. Unexplained actions, surreal figures and constant non-sequiturs had appeared throughout but they remained no less eerily transfixing.

Laura’s promise, within the context of the show, occurs inside the Black Lodge. This is a liminal zone that exists between the small town that the series is named after, its surrounding Douglas fir forests and that which lies “beyond”, a metaphysical crossing-point between life and death, good and evil.

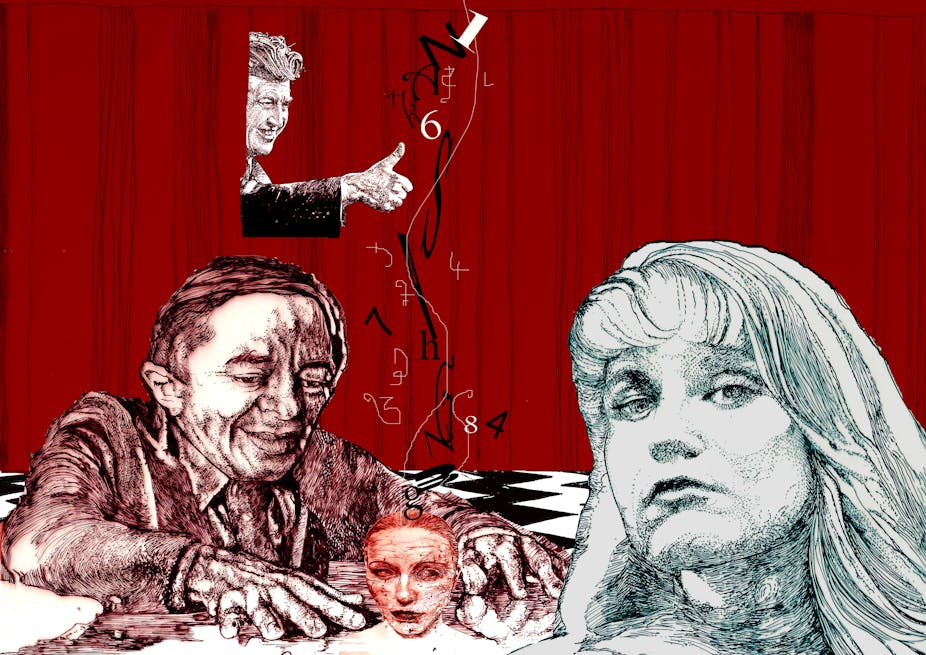

It is visualised as a room of zigzagged floors, black couches, white statues and gently swaying red curtained walls wherein time is fluid and speech is spoken backwards. Long before Rust Cohle (played by Matthew McConaughey) intoned about time being a flat circle in True Detective (2014), Twin Peaks abounded in existential enigmas.

In the Black Lodge, bodies appear and disappear; time loops; lights flicker and wrenching screams fill the air. Like the experience of watching Twin Peaks in general, the Black Lodge scenes are so aesthetically singular, so highly stylised, and at times so frankly terrifying that it is hard to imagine how David Lynch and Mark Frost’s co-creation was greenlit by and aired on prime time US network television.

At a time in which network rather than cable TV programming held clout, Twin Peaks was, initially at least, commercially and critically successful, garnering 14 Emmys and some of the highest ratings that ABC had netted in years.

Looking back, Twin Peaks had no shortage of ardent supporters and fans.

Its riddling, quixotic sensibility spread out far beyond the textual confines of the show and into a range of concurrent popular culture forms. In The Simpsons, for instance, Homer is seen laughingly watching a mock Twin Peaks episode before exclaiming: “I have absolutely no idea what is going on.”

There was a Saturday Night Live parody, cross-media spin-offs (The Secret Diary of Laura Palmer, penned by Lynch’s daughter Jennifer Lynch, or The Autobiography of F.B.I. Special Agent Dale Cooper: My Life, My Tapes), coffee ads as well as endless magazine covers with the cast.

Furthermore, as media fandom scholars such as Henry Jenkins have observed, Twin Peaks was one of the first shows to launch nascent forms of TV/internet fandom. Its first audiences took to online bulletin boards and forums, together with VCR recordings and fanzines to collectively try and make sense of a deliberately obtuse show.

When the network placed the show on hiatus after the first season, the fans passionately rallied around the show imploring the network to “Give Peaks A Chance”.

What went wrong? Arguably, the downfall of Twin Peaks actually had very little to do with the quality of the show or with Lynch/Frost. Sure, there were plot lines we could all have lived without. For myself, that involved anything to do with the town mill or the seemingly endless and ill-fated Windom Earle storyline that dominated the end of season 2.

The real “problem” with Twin Peaks was that it simply did not cohere with the conventions, demands and audience expectations of network TV during the early 90s. When audiences dropped off because the question of who killed Laura Palmer still had not been answered, ABC responded by changing programming days and times and then cancelling the show.

Lynch himself (unlike the more TV-schooled Frost) has made no secret of the fact he never wanted to reveal who killed Laura. He would have preferred, instead, to leave that question unanswered so that it might generate still further enigmas. When network pressures forced the show to reveal Laura’s killer, Twin Peaks provided an answer while defiantly opening up other existential questions. The Black Lodge, aliens, doppelgängers. Killer BOB.

The real legacy of Twin Peaks is not who killed Laura or any of the other narrative mysteries that followed. It is how this show managed to be (and still is, upon reviewing) so powerfully and affectively mysterious. From the oneiric opening credits on, you felt like its seemingly innocuous, small town, beige carpeted reality could, at any moment, give way to an entirely different, unnerving world.

The click of a record player, BOB steadily crawling over the lounge room couch, the movement of the ceiling fan, the sway of a traffic light or that low humming drone that resonated throughout. The use of images and sounds in Twin Peaks become the stuff and substance of nightmares.

To date, I can only think of one TV show that even comes close to achieving that kind of surrealist atmospherics whereby one reality subtly and seamlessly enfolds into another – Hannibal (2013-).

This week it was announced that Twin Peaks is set to return for a third season on Showtime in 2016 – 25 years after Laura promised she would see Cooper again. Purported to be a direct continuation of where the last season left off only set in the present day, there has already been much anticipation, speculation and hesitation.

Social media is rife with different generations of Twin Peaks fans trading those old but familiar quotes (“it’s happening again”; “that gum you like is going to come back in style”), demanding to be the new Log Lady, and wondering whether or not we will know Cooper’s fate.

With Lynch/Frost at the helm once more and Lynch set to direct all of the nine slated episodes, questions abound. How will the new Twin Peaks stack up against its slick, stylish and nightmarish cable brethren? Will it be as disturbing, as hilariously funny and as wildly multi-generic as the original? There is some time yet before any of those questions can be answered.

Let us hope that the contemporary age of “quality TV” and “narrative complexity”, particularly on cable, will finally give Lynch/Frost room enough to play.