Tasmania. It’s not at the ends of the Earth, but it was the last place I thought the pejorative term “Essex girl” would find me. When my working-class Colchester childhood came up in conversation with an elderly male university lecturer, his sideways wink and lecherous grimace suggested that even at the southernmost tip of Australia one couldn’t escape the misogynistic connotation associated with the moniker.

With that one gesture I believed all the professional and academic credibility I’d established as a mature university student was peeled away. What was left was the imposter of a woman defined by the hostile double whammy of class and gender stereotypes.

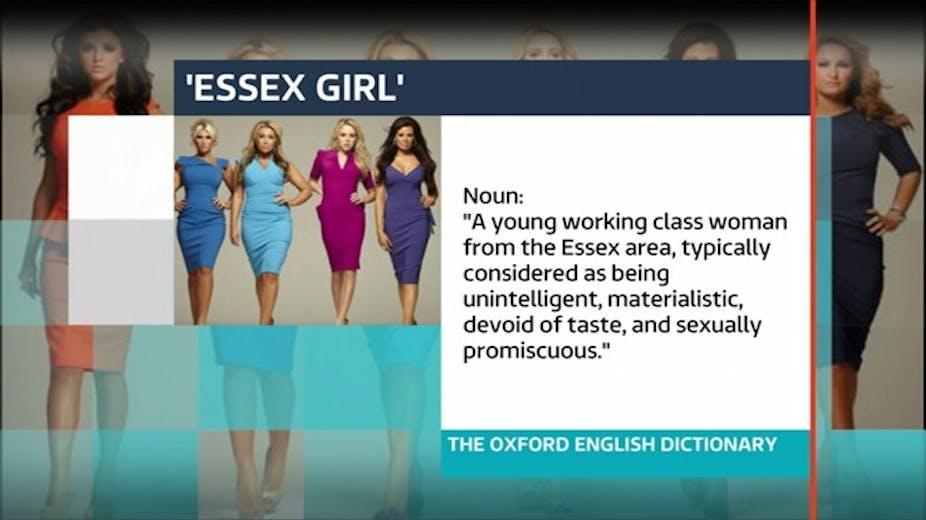

Variously defined as an unintelligent, sexually promiscuous woman with garish fashion sense, lacking in social graces and standing, the term “Essex girl” prominently entered the lexicon in the late 20th century with the popularity of television shows such as Birds of a Feather and, later, The Only Way is Essex (TOWIE).

While it could be said that the use of the term is “jovial”, the associated jokes and jibes underpin a misogynistic rhetoric descriptive of women who have social aspiration and mobility coupled with a command of their own sexuality. In isolation, these behaviours are often met with snobbery and derision but together they are perceived to deliver a dangerous cocktail of self mastery, rejection of social convention, independence and increasing consumer power.

Historically, women who stepped outside gender and (heaven forbid!) social convention were seen to be in need of discipline to reel in their behaviour. In a piece on the “Essex girl” phenomenon from 2001 – which just goes to show how long we’ve been putting up with this – Germaine Greer points out that forthright women are embedded in the fabric of Essex history:

Essex was always noted for its ducking stools and scolds’ bridles, and for “witches”, which is just another name for uncontrollable women.

One might suggest that the recent attempt to have the term removed from the dictionary is an overreaction to a “jovial” term that means little in reality. It isn’t.

Words matter

There is a body of research that identifies that discriminatory practices, particularly in the labour market, can be linked to residence and background. The origin of an applicant can trigger bias, regardless of the stated skills and capacities outlined in written applications. It follows, then, that similar overt discriminatory practices may be applied to women who carry with them a negative “Essex girl” stereotype simply by virtue of their background or residence. While overt discrimination of this nature may, on occasion and with evidence, be challenged, it is the implicit bias (unconscious, first thoughts and actions) that terms such as “Essex girl” perpetuate. This is far more insidious.

Language is a magical and powerful thing. It gives us the capacity to manifest thoughts and ideas, and to develop a shared meaning. Words are invested with value and intent. If one is aware of the disparaging definition of a term such as “Essex girl” then the characteristics will be applied to the individual to whom it is directed. The stereotype allows us to quickly, and often erroneously, apply understanding about an individual based on a few selected characteristics. That understanding then informs thinking and behaviour.

Work undertaken by Dr Doug Martin and colleagues suggests that as stereotypes become used more frequently, attributes become more polarised. They deliver meaning that is far more binary – good/bad, positive/negative. The highly simplified bits of information invested in terms such as “Essex girl” become more readily identifiable and entrenched.

In the instant that lecturer leered and winked, the unstated meaning of the term was shared. By virtue of my social and geographical background I was no longer an educated professional woman undertaking a university education, I was a promiscuous bimbo reaching above my station and disparaged for seeking social mobility. I felt belittled and aggrieved. The words had allowed him to put me “back in my place” and, while it may be said that it was not his intent, that was the result. If I had come from Oxford, say, I doubt his behaviour would have been the same.

As International Women’s Day rolls around again, we are offered an opportunity to reflect on how women fit into the world, our achievements, contributions and our future.

Invariably we will see reports about the gender gap, and the continued lack of female representation in certain areas of society (in the boardroom, in politics and in the sciences, for example), and we will make a case as to why, as a community, we need to keep discussing and questioning the status quo.

If we are to make more rapid advances towards equality in pay and status, we need to retire the idea that terms such as “Essex girl” are only meant in jest. Continuing to entertain the use of erroneous and disparaging terms such as this only perpetuates the bias and hostility.