Composers count themselves lucky when musicians continue to perform their music after their death.

But the American avant-garde composer John Cage, who died in 1992, never would have guessed that a single performance of his music would begin in 2001 and still be playing. In fact, it isn’t due to conclude for another 616 years.

In a marathon performance like this, any little change becomes big news. On Feb. 5, 2011, for instance, one of the first three notes stopped sounding – after being sustained for eight years.

On Feb. 5, 2023, another note is going to begin playing – the first since Feb. 5, 2022. This one will be relatively short; it will hang around for only the next two years.

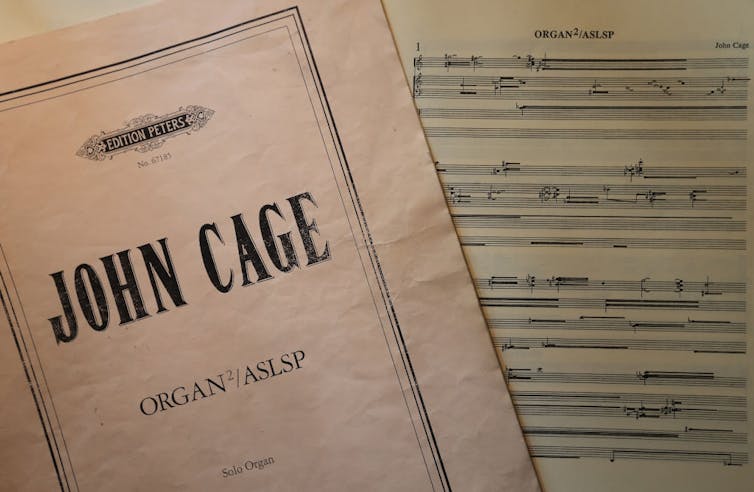

The piece is called “Organ2 /ASLSP.”

“ASLSP” refers to the phrase “as slowly and softly as possible,” a reference to a quotation that appears near the end of James Joyce’s novel “Finnegans Wake” – “Soft morning city! Lsp!”

Originally written for piano in 1985, Cage made an arrangement for organ. Like the piano score, Cage never specified how long the piece should be played. Most of its performances have lasted between 20 and 70 minutes.

At a talk prior to the work’s German premiere in 1987, the musicologist Heinz-Klaus Metzger wondered aloud – half jokingly – how long a performance should last, since an organ can sustain sound indefinitely. A group of organists, artists, scholars and theologians took Metzger’s question and considered how a very long performance might become a reality.

The performance is taking place at the St. Burchardi Church in Halberstadt, a small town in central Germany some 133 miles (214 kilometers) southwest of Berlin. The church dates from 1208, and in 1361 a large organ was installed, one of the first to have a keyboard of the type that is now universally used for pianos and other such instruments.

That organ is long gone, but this history inspired the organizers to choose the site for the event. Builders constructed a much smaller instrument and installed it in the church, one just large enough to accommodate the sparse number of musical notes in the piece.

Is this strange piece of music a joke? A grand artistic utterance? An everyday event? Sometimes I’m not sure myself, and I’ve been studying Cage and his music for the past 25 years.

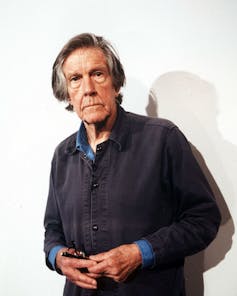

A provocative composer

During his lifetime, John Cage was no stranger to controversy. He was one of the first classical composers to write music for percussion instruments only, because he felt that any sound could be used in music.

But his most famous – maybe notorious – composition is “4ʹ33,ʺ” a piece with no sounds at all.

There are countless explorations of what the piece means; one of the best is by musicologist James Pritchett, who traced Cage’s interest in silence to his studies of Eastern spiritual traditions and a growing dislike for the materialism of the West.

For me, it’s a great illustration of Cage’s interest in Zen Buddhism.

Zen has to do with becoming aware of everything in life. The ugliest thing is just as important as the most beautiful. Another important concept is that it’s far better to enjoy things while they last, precisely because they won’t last.

When you listen to “4ʹ33ʺ,” you’re hearing whatever sounds happen to be around you during a performance. You’re always going to hear something different, and you always get the chance to hear something that you might have ignored otherwise.

Eventually Cage began to feel that composers should just let sounds be sounds. They shouldn’t try to string them together to make people feel a certain way or think about a particular topic.

He did this through the use of what he called “chance operations.” Cage thought of musical composition as a process involving a series of numbered possibilities for every aspect of the music. For instance, in a piece for two pianos, Cage numbered all of the possible notes. He then used specially designed software to select which ones would appear in the piece. Another chance operation would answer the question of whether that note would be part of a chord and, if so, what the additional notes were. It’s a very time-consuming procedure.

Cage accepted whatever sounds the chance operations identified, since the sounds were pleasurable on their own. Late in life, he elaborated on this idea:

“I love sounds – just as they are. And I have no need for them to be anything more than what they are. I don’t want them to be psychological. I don’t want a sound to pretend that it’s a bucket, or that it’s president, or that it’s in love with another sound. I just want it to be a sound.”

That sometimes leads people to think they should have no feelings at all listening to Cage’s music. But Cage loved sounds, and love is certainly a feeling.

Would Cage have approved?

Naturally, a composer who took such a radical approach to music runs the risk of performances that reduce his ideas to absurdity.

I remember preparing a performance of his “Song Books” in Amsterdam where one of the musicians decided to interpret Cage’s instruction for an “auxiliary sound” as an invitation to produce an imitation of flatulence. I gently advised the musician that Cage had always tried to make musical compositions that sounded unlike anything he had heard before; as he wrote in his second book, “A Year from Monday,” he wanted the freedoms that he composed in his music to be taken seriously by performers, to make them nobler people.

I thought about this when I first began learning about the Halberstadt organ project.

No performers are sitting at the organ, day in, day out, in the cathedral where the piece is being performed. Instead, an electronic bellows pumps air into the organ; the individual-sounding notes are made from inserting or removing pipes of various lengths into the organ as they’re needed.

A 639-year performance of a piece of music, it seemed to me, was a poor use of human and environmental resources – and more of a gimmick than it was a real piece of music. I said as much in my book on Cage published in 2012, noting with dismay that Germany’s public broadcasting system, Deutsche Welle, erroneously reported that Cage himself planned the extraordinary duration of the work.

It was only last year, during a podcast conversation with Laura Kuhn, the executive director of the John Cage Trust, that I was able to see the “Organ2 /ASLSP” performance in a new light.

Thinking aloud about the various ways that Kuhn has brought others in touch with Cage’s ideas, I realized that Cage was, above all, a composer who sought out new ways of making music. The organ performance certainly demonstrates that artistic impulse.

In a way, it’s also another great illustration of Zen: The sounds last so long that they simply become a presence, like wind in the air or clouds in the sky.