Recent findings by the Australian Crime Commission suggest Australians are consuming more cocaine than ever. Far from the buzzing beach-side nightclubs of Sydney, where I grew up, I recently had a chance to see the devastating effect of the illicit cocaine market on Colombia’s public health and security first-hand.

In September of 2012, the mayor of Bogota launched an unprecedented public health initiative to provide medical attention to the gravest cases of drug addiction in the most degraded and feared zones of the city. One of these zones is “El Bronx”, which, according to official figures, houses around 20% of the city’s 10,000 homeless population.

A nucleus of criminal activity, El Bronx is where addicts and the homeless pawn stolen Blackberries, where counterfeit money is traded, where children are trafficked into prostitution, where hit men are contracted. The addicts and debris are mere overgrowth.

This criminal offspring of Bogota’s sprawling informal sector (around 60% of Colombians are either unemployed or engaged in informal, unstable employment) is tightly controlled territory, overseen by one of Bogota’s wealthiest criminals, who, I’m told by officials, lives in the city’s affluent north. But it is also home to street poets, homeless writers, even a singing duo who rehearse inside before heading out into the wider city to busk.

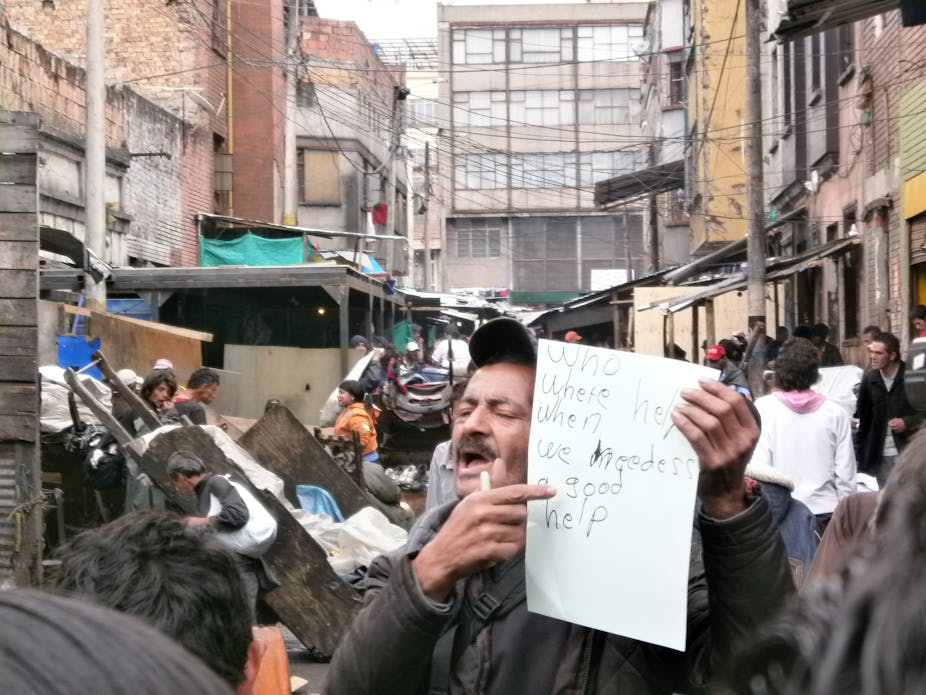

What unfolded when the mayor visited was an extraordinary encounter between the abject and all that glitters – officials’ cars rolled in, an events tent and stage were assembled. Journalists watered at the mouth (it’s rare that they can even get a shot of this notorious area, but the security detail and high volume of attendees created a buffer zone).

Then the intervention began. The brand new white medical unit pulled up outside the barricade that blocks entry to the street. A garbage truck entered to carry out the sanitation process, emerging with mounds of rubbish as high as the humans inside.

When the mayor of Bogota arrived and took the stage, police, public servants and ministers huddled under umbrellas as locals moved through the crowd. There was a palpable sense of “how much longer?” among the staff – one member of the mayor’s security detail leaned in to me and whispered “cover your mouth, they’re all swarming with tuberculosis”.

Also referred to as “La L”, due to the shape of the market’s thoroughfare, El Bronx is less an “L” and more a “U” – one walks in, across, doubles back and exits. There’s the canteen where occupants can buy a mound of gruel, speckled with mould and served on a sheet of newspaper. It goes for 1000 pesos (US 55 cents). To put this into perspective, a beggar might receive 100 or 200 pesos with each handout, 500 if he’s lucky. Someone may therefore have to beg up to ten times for this rancid Mr Whippy-shaped mound. Better to invest in a daily supply of the zone’s cheapest drug for around 6000 pesos (US$3.20).

Strolling through the main thoroughfare, I see people twitching and contorting. For every group of people sitting around smoking joints, there are another seven or eight packed together, sleeping, wrapped in blankets in spaces that resemble pigsties. On the second floor are the snipers keeping watch. They have guns in backpacks that rest against their legs. I can’t make them out too well, but I’m told that upstairs is a different world – in between shifts the snipers switch seats, the other of which faces a flat-screen television.

I ask my guide about the imposing group of young men playing pool. They show no signs of malnourishment, addiction, or desperation. “Those are the guards,” my guide tells me. The guards play a vital role in maximising profit. “People from every strata of the city come here to score. But they need security when they pull up in their expensive cars.” The role of the guards is to ensure that upper class addicts are neither robbed nor attacked by the Bronx-dwellers. The approaching buyer will call one of the guards and request that he escort them through the market or bring the drugs to the car.

Still, I’m assured that there is no violence inside, only on the outskirts where addicts leave to rob those not from the Bronx (it’s just a few blocks from the Presidential Palace). Inside is controlled, the snipers poised in case the police enter (they don’t), in case the territory is challenged, or a reporter comes snooping.

My chaperone from the city office introduces me to three individuals and stresses that I must deal only with them. One is younger, in his early 20s, and asks me to help him “find a good education”. The request is entirely indicative of the state of Colombia’s public institutions. At events such as these – community outreach, state-financed community events – where the privileged fleetingly cross paths with the marginalised, the latter snatch at any short-term gain the former can offer.

And the greater the divide between the fortunes of both teams, the more brazen the snatch and grab effort. Drug addiction has added an extra layer of desperation. Addicts beg journalists and officials (some retreat to their cars for peace). Based on my own interactions with incoherent locals, I have agreed to smuggle someone into Canada and film a documentary with another.

People disappear for decades into these parts of the city, and not just Colombians. A city official had earlier told me that it is not uncommon for tourists to come to Colombia, party too hard, lose their bearings, cash and minds, and end up here. People disappear for decades into these parts of the city.

This is where the term “olla” comes from. Colombians use it to refer to the uninhabitable parts of the city, the sites of transgression, vice and criminality that no one dares enter. I misunderstood the term for many months, having never sought out the exact translation. And then one day, the term surfaced again, at entirely the other end of the income spectrum as I was enjoying a weekend at a friend’s expansive country house helping out in the kitchen.

“That’s an ‘olla’?” I asked, pointing to a ceramic casserole dish my friend’s mother was using. “Yes,” she replied, “you toss everything in, seal the lid, and let it simmer for hours”.

Still unclear on the origin of the term in the context of rough neighbourhoods, I asked her to explain. “Well, I suppose, because once you’re in there…”, in went some chopped cilantro and the lid was sealed. “There’s no way out.”