Climate change is real, it’s accelerating and it’s terrifying. We are adding carbon to the atmosphere at a rate 100 times faster than any previous natural increases, such as those that occurred at the end of the last ice age.

The effects are easily made visible through dramatic images of rapidly shrinking glaciers or the Amazon rainforest on fire.

But pictures like these can distance us from environmental catastrophe, turning it into something spectacular, arresting – even paralyzing. They don’t communicate the everyday impact of climate change, which is also taking place in our own backyards.

In the book I’m currently writing, I’ve made these smaller, less obvious effects my focus. I explore the work of artists and poets who help us understand how the smallest changes to the environment can signal large-scale damage.

They build on a crucial legacy left by Victorian observers of the natural world who emphasized the need to pay careful attention to the tiny details of our surroundings.

Observant Victorians

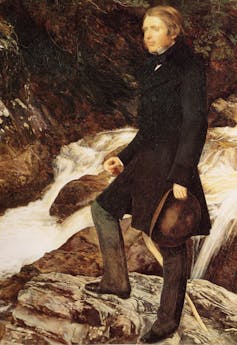

No one was more insistent on the importance of looking closely at the ordinary and the everyday than the 19th-century art critic and social thinker John Ruskin.

His advice to “go to Nature … rejecting nothing, selecting nothing and scorning nothing” inspired many artists of the era – British artists like John Everett Millais and John Brett, and American painters John Henry Hill and William Trost Richards.

Meanwhile, books and articles, such as J.G. Wood’s “Common Objects of the Country” and Anne Wright’s “The Observing Eye,” popularized scientific observation as a practice available to all, teaching people to find wonder in the world about them – in “the sky, the leaves and pebbles,” as Ruskin wrote.

Many contemporary artists have picked up the baton, showing how three very ordinary species from the natural world – dandelions, fireflies and lichens – can stimulate our imagination and make us think about climate change in new ways.

The resilience of dandelions

Few plants are more ubiquitous than the dandelion.

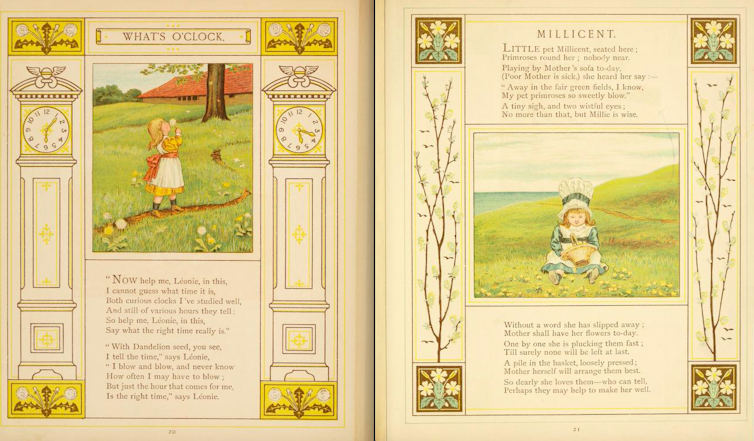

In the 19th century, its yellow flowers and decorative fluffy seed-heads often appeared in sentimental paintings of children gathering dandelions in meadows or of young women blowing on gossamer puff-balls. They flourished in nursery rhyme illustrations and on decorative tiles.

The flower was useful in the kitchen, too: Victorians ate it in salads and drank it in teas.

But at some point in the 19th century, its status morphed. Dandelions became a weed.

As all gardeners know, they are persistent. Weedkillers like sodium arsenite were introduced in the late 19th century. After World War II, powerful chemicals were developed for lawn maintenance, doing far more damage to people and the environment than dandelion roots. Gardening websites are still full of references to “the war on dandelions.”

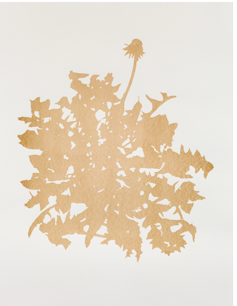

Today, British artist Edward Chell wants us to think about the damage done to these exiled weeds. He picks dandelions and other wild flowers on Britain’s motorway verges – micro-habitats choking with pollutants that nonetheless sustain diverse vegetation.

Using a silhouette drawing technique borrowed from the late 18th century, he draws the plant in outline and fills it with a mixture of ink and dust taken from the motorway. His images show the beautiful fragility of roadside weeds. But they’re also records of toxicity, made with the residue of the internal combustion engine: unburned hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides and particulate matter.

The jagged edges of the dandelion have a starring role in his series. But for Chell, the flower no longer symbolizes sentimentality and innocence, as it did in the Victorian era; instead, it’s mutated into a chilling commentary on roadside pollution.

The magic of fireflies

In a threatened world, nature exerts a nostalgic pull. For many Americans, thoughts of fireflies transport them to the long, warm summer evenings of childhood.

Fireflies enjoy a double life: By day, they are unremarkable, dull-brown insects; by night, they are captivating sparks that dance together.

Victorian writers and artists saw magic in these floating dots of light, comparing them to fairies and goblins. The firefly’s grip on the imagination was so strong that it inspired scientists to search for ways to explain the mysteries of bioluminescence.

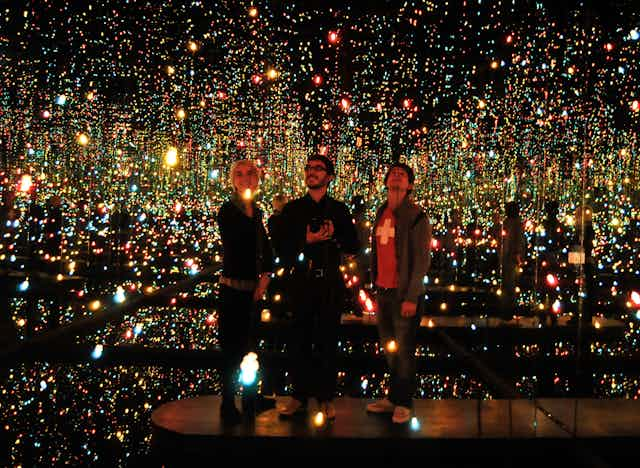

The magic of fireflies persists. Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama has constructed several firefly installations that were inspired by a Japanese folktale about an old man in a field who was robbed on a pilgrimage. In Japanese culture, fireflies stand for the soul: In the tale, thousands of fireflies attack the man’s assailants after his death.

The Phoenix Art Museum features one of Kusama’s installations. Visitors can stand in a pitch-black room of mirror-lined walls, polished black granite floor and a black plexiglass ceiling, from which 250 LED lights hang and flicker like fireflies on a continuous two-and-a-half minute loop.

To stand here is to experience infinity. It recalls the extraordinary beauty, yet fragility, of our natural environment.

And then you might wonder: When did I last see fireflies?

Fireflies have become increasingly uncommon – victims of habitat loss, pesticides and light pollution. Kusama’s project, involving so many dancing electric dots of light, may be understood as a deeply ironic one.

The sagacity of lichen

It’s not just artists who give significance to the small and overlooked.

Art historians can direct our attention to something we take for granted.

Mid-Victorian paintings are best known for their depictions of modern life, for dramatizing the personal side of historical events and for introducing us to stunning landscapes.

But I suggest viewers concentrate on the apparently insignificant in these works; examine and think about the lichen that clings to rocks, tree trunks and walls in paintings like Millais’ “A Huguenot” or Brett’s “Val d'Aosta.”

The very lichen that was painted in the mid-19th century likely contained traces of the substances that would destroy it.

For lichen is – as the Victorians came to realize – a bellwether for a polluted climate. Too much pollution near a big industrial city, and it disappears from tree trunks and stones.

Because of its quiet beauty and its vulnerability to environmental change, lichen has become a powerful symbol for fabric artists, poets and installation artists.

Yet lichen is the consummate survivor. It appears quickly after nuclear disaster or on newly solidified lava. What’s more, lichen possesses properties – collaboration, determination, endurance – that humans will need to survive climate change.

“We are all lichens now,” wrote eco-scholar Donna Haraway, referring to the symbiosis and codependence that characterizes lichen – and that increasingly will come to define the human experience.

Looking at 19th-century depictions of nature doesn’t just lead to a nostalgic lamentation of all that’s been lost.

Instead, it inspires us to try to grapple with the present – and spurs us to intervene in our future.

[ Like what you’ve read? Want more? Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter. ]