Leer en español.

Three-quarters of all abortions in Latin America are performed illegally, putting the woman’s life at risk. Together with Africa and Asia, the region accounts for many of the 17.1 million unsafe abortions performed globally each year, according to a new report in The Lancet, published jointly with the Guttmacher Institute, a research and policy group.

Though worrying, this fact is unsurprising in a region where six countries ban abortion under all circumstances: the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua and Suriname. Such complete criminalization, even when fetal termination is necessary to save a woman’s life, exists in only two other places in the world: Malta and the Vatican.

Numerous studies confirm that restrictive laws do not in any way prevent women from seeking or getting abortions. And in the vast majority of Latin American countries – including Argentina, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Venezuela and, since August 2017, Chile – this medical procedure is legal, though it generally requires specific justification, such as maternal health or rape.

Not so in Central America, home to three of the eight countries in the world with total abortion bans. As I am a Costa Rican lawyer and feminist, to me, it’s no small matter that women in many neighboring countries lack access to this basic health service.

Why does this region so studiously avoid recognizing women as full individuals entitled to their own human rights? In my view, there’s a clear link in Latin America between the state of a country’s democracy and the reproductive rights of its female citizens.

Honduras: Land of inequality

In Honduras, for example, it was only after the 2009 coup d'état that ousted President Manuel Zelaya – a huge democratic setback that ushered in an era of violence – that the country passed a total ban on abortion.

Today, women must carry to term even a pregnancy that endangers their life, and emergency contraception is heavily penalized. These restrictions were reaffirmed by the Supreme Court in 2012.

Despite efforts by human rights defenders and official statements by the United Nations, independent experts and NGOs like Amnesty International, there has been no material progress in advancing the reproductive rights of Honduran women.

In some ways, this is not surprising. In post-coup Honduras, human rights violations – ranging from violence and poverty to impunity – are routine fare for the entire population. Rampant gender inequality is just another symptom of this dismal situation.

Nicaragua and El Salvador: Dangerous setbacks

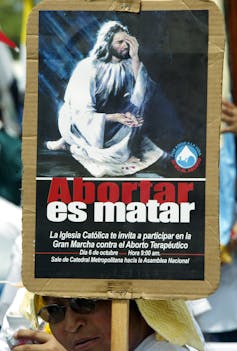

The situation in Nicaragua, just to the south, is similar. There, “therapeautic abortion” – the common parlance for ending a pregnancy for health-related reasons – was acceptable from 1837 until relatively recently. But starting in 2007, President Daniel Ortega, who has modified the Constitution to end term limits, began passing legal amendments to ban abortions completely, without any exceptions.

Ortega supported abortion rights during his first presidency, in the 1980s. But he has since embraced the Catholic Church’s position of strong opposition, with deadly consequences for Nicaraguan women.

In 2010, for example, a pregnant woman who went by the pseudonym of “Amelia” was refused treatment for metastatic cancer because the state ruled that the regime of chemotherapy and radiotherapy – which her doctor had urgently recommended – might trigger a miscarriage.

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights ultimately issued injunctions for Amelia, but the damage was already done. She died in 2011.

Impossible though it may seem, women fare worse in El Salvador, a civil war-torn country rife with violence, unpunished crimes and criminal infiltration of the police. In 1999, El Salvador constitutionally mandated that human life starts at the moment of conception.

This legal argument is now used to uphold a full criminalization of abortion, even under the most extenuating circumstances, such as when a woman’s life is at risk, the pregnancy is the result of rape or the fetus is severely malformed.

Anti-abortion sentiment is so virulent in El Salvador today that even miscarriages may be investigated on suspicion that they were self-induced. This persecution has had lethal consequences: Women who’ve spontaneously lost a pregnancy have been accused of murder, sometimes by even their own law-abiding relatives.

In 2016, Sweden offered political asylum to a Salvadoran woman who was sentenced to 40 years of prison for the aggravated homicide of a fetus miscarried before she even knew she was pregnant.

The United Nations Committee on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women has requested that El Salvador decriminalize abortion, saying that the fact that most women prosecuted and sentenced for this crime are among the country’s most vulnerable citizens – young, uneducated, jobless and single – represents a powerful social injustice.

Women’s citizenship

Though there are great economic, cultural and political differences between these three countries, across Central America the connection between the lack of rule of law and women’s restricted reproductive rights is noteworthy.

That’s because denying women the ability to make decisions about their own bodies means that a woman’s life matters only to the extent that she is the custodian of a potential future life, rather than as a life worthy of protection.

The Constitutional Court of Colombia agrees. In 2006, it stated in its legal justification for decriminalizing abortion, “The dignity of women does not permit that they be considered mere receptacles.”

In Chile, which recently legalized abortion after nearly a half-century of its total prohibition, history shows a similar relationship between democracy and women’s rights. In 1931, the Chilean Congress approved the voluntary interruption of pregnancy for medical purposes if the woman’s life was endangered or the fetus was not viable.

This exception remained in place until, in 1973, under the dictatorship of Augustin Pinochet, abortion became illegal. In 1980, the Chilean Constitution established that the law protected the life “of the unborn,” indicating that the life of a woman was worth less than that of an embryo.

Even after democracy was restored to Chile, in 1991, this ban remained in place. It was not until August 2017, some 26 years later, that the country adopted a more sensible approach, focused on protecting women’s lives and health. The Chilean case demonstrates that once women lose their value as individuals in the eyes of the state, it is difficult to win back.

What’s at risk in the Latin American regimes where abortion is still forbidden, then, are not only women’s lives but also the political systems of Central American society itself. Can democracy exist in places that don’t recognize women as people?