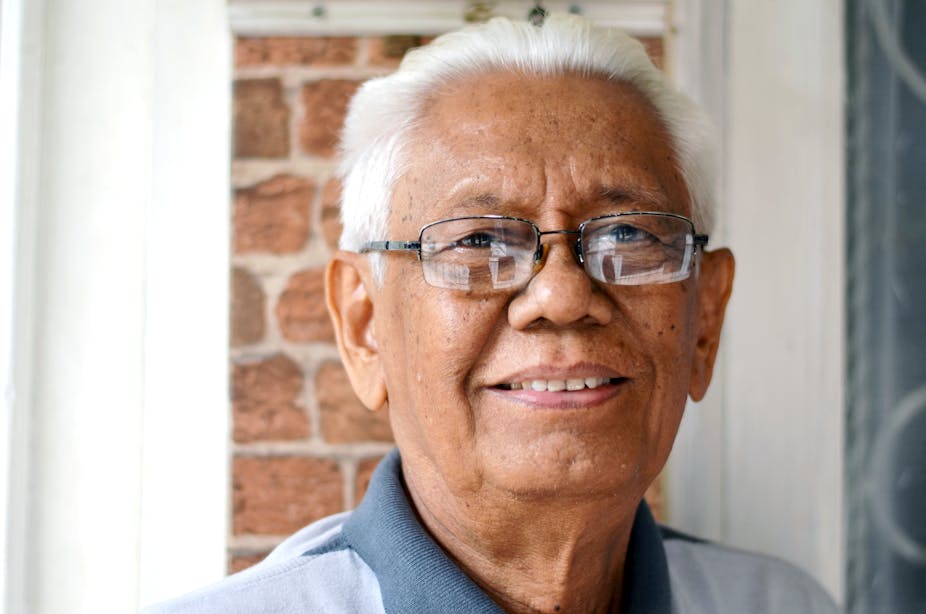

As Indonesia becomes the world’s COVID-19 epicentre, writer and activist Putu Oka Sukanta’s poetry reflects how the pandemic has changed human relations and ways to maintain optimism and resilience.

As a former political detainee – Sukanta was imprisoned for ten years without trial by Suharto’s New Order regime and is one of the diminishing numbers of survivors of the 1965-66 mass violence in Indonesia – he knows too well the government’s shortcomings in meeting the needs of the country’s most vulnerable.

Official statistics show 100,636 Indonesians have died of COVID-19 as of August 4. However, the data monitoring group Lapor COVID alleges that deaths are being seriously underreported by the national government. About 30% of these deaths occurred in July.

The government refrained from taking decisive action, concerned about the impact of lockdowns on the economy. In March 2020, the government issued an order for large-scale social restrictions. But left to regional governments, its implementation was inconsistent across the archipelago.

At 82 and with a heart condition, Sukanta has been in self-imposed isolation in the past few months. A couple of members of his multi-generational household recently contracted the virus.

During his prison days, Sukanta found himself dreaming of solitude. Now, despite living in a household with five others, there is a surfeit of aloneness. He feels the aches and pains of boredom, unable to sit for too long to write and create these days.

Yet, he writes, as in the poem “I hope”:

I hope

to hear knocking at the door

that I have kept closed,

though not completely locked

I hope

to see shadows

come and go in the window, but

only the roar of the wind

greets the cold drizzle

I hope

to hear knocking at the door, or

if not, just a shadow passing by

in the window

so that I can speak

of my happiness, of how much I miss you.

Being a political activist, Sukanta does not ignore the violent coup in Myanmar. Women hanging up their underwear to deter soldiers from pursuing protesters inspired him to write the poem, “Myanmar Military vs Women’s Underwear”, addressing his friend and Indonesian human rights activist, Galuh Wandita. An extract of the poem reads:

Hey, Galuh

let’s shout out:

women of the world, send

your old underwear to Myanmar,

(preferably blood-stained ones)

sew them into flags, waving and flying,

blocking their path, confronting and conquering

the hunters.

Sukanta told me: “I’m a political animal. Writing about politics is like a reflex to me.”

But he has found that he has become guided much more by emotion, letting the writing urge dictate when he writes. “I’m more ikhlas, pasrah (inclined to let go).”

As a former political detainee, the capacity to be self-sufficient financially is vital to his sense of independence and well-being. While in prison, he learnt acupuncture from his fellow inmates. He put these skills into practice when he became an acupuncturist and herbalist.

Sukanta had a home practice, seeing patients three times a week and prescribing herbal medicines. These herbs are grown in Taman Sringanis, the garden south of Jakarta that he and his wife manage. Concerned about the pandemic, though, he closed down his practice in March 2020.

One of the things he misses most is the hubbub of the clinic. “This house was a noisy house,” he explained. “My patients are like books. I learnt from them. They provided me with stimulus and dialogue.”

Students, buskers and beggars also frequented his house, stopping by to ask for information and help. “Suddenly, all fell silent. Naturally, I felt sad, like I had lost a great deal. I felt a sense of being in exile.”

For Sukanta, self-isolation had some similarities with his experience of political detention. Prison was also devoid of the sounds of the streets, “of goats, children, and so on”. But in prison, despite having lost his rights, he had felt a sense of purpose, of a “common enemy” that had to be overcome, the New Order regime.

With this pandemic, “I have rights, and I cannot exercise them [due to the pandemic]. Inwardly, I ask myself what I can do in this situation.”

As a health practitioner, he sees the need to develop strong health-care systems and use preventative measures.

He is critical that the Indonesian government approach focuses on treating disease rather than prevention through adequate nutrition and good health care. “Curing, rather than prevention is the focus. [The attitude seems to be] get sick first, then think of the cure.”

Surviving on minimal health care while in prison, Sukanta sees that Indonesians are trying to boost their immune systems to avoid falling ill in the face of a health system in crisis.

“The idea that food is medicine, medicine is food is not new, but it’s getting more traction due to the need to increase one’s immunity in times of COVID,” he said.

Growing food has now become a hobby, and a means to supplement one’s income in the capital city.

For Sukanta, his savings have dried up, “I only had enough for a maximum of a year. [The pandemic] has been more than a year now.”

Royalties from his books have slowed to a trickle as publishers struggle, with books being luxury items in a time of the pandemic. “Our income has shrunk, while things like electricity consumption obviously can’t be reduced.”

A survey by SMERU Research Institute last year showed 74.3% of households reported a fall in income due to the pandemic, yet living costs are rising. The workers at the Sringanis herbal garden have not been laid off, but their wages are paid only in fits and starts.

The pandemic has taken a terrible economic and social toll, not least on people’s sense of dignity, and has exposed the shortcomings of Indonesia’s health system. Attempting to fill the gap, fundraising efforts to support those tackling COVID-19 in Indonesia are growing.