The Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) yesterday recommended introducing new laws that would give a legal remedy for serious invasions of privacy.

Unfortunately, the federal government has already indicated it opposes such legislation. Stronger protections of privacy in Australia are needed though, and the proposed privacy tort is the best way forward.

In its inquiry on Serious Invasions of Privacy in the Digital Era, the ALRC considered whether Australians should have legal redress if their personal sphere is invaded without their consent.

With its proposal for a statutory cause of action to protect privacy, the ALRC reaffirmed a recommendation from its 2008 landmark report on privacy. The New South Wales Law Reform Commission in 2009 and the Victorian Law Reform Commission in 2010 also made similar calls for enhanced protections.

Despite these repeated calls and the growing community concern over loss of privacy in recent years, successive Australian governments have shown little appetite for improving Australia’s privacy regime.

Australia is now virtually unique in not recognising a right to privacy. In most other common law jurisdictions, courts have developed specific protections against invasions of privacy.

In New Zealand, the UK and, most recently, Canada, judicial developments have been prompted by human rights legislation. These countries’ bill of rights guarantee fundamental freedoms, including the right to freedom of expression and a right to respect for private life. The absence of a federal human rights framework in Australia hampered the development of a common law right to privacy.

It is this legal gap that the ALRC now recommends to fill.

The proposed privacy tort

The ALRC report carefully evaluates the various interests that collide in cases of privacy invasions. It proposes federal legislation for a new tort of serious invasion of privacy that would focus on:

- intrusion into seclusion and

- misuse of private information.

The ALRC recommends that the tort should be confined to intentional or reckless invasions of privacy, so that negligent invasions of privacy would not be actionable, and to introduce a requirement that the invasion must be serious.

Most importantly, it is proposed that an action could only succeed if the court was satisfied that the public interest in privacy outweighed any countervailing public interests. This requirement for a balancing exercise would ensure that freedom of speech, freedom of the media, public health and safety and national security would not be disproportionately curtailed.

The recommendations of the ALRC are the result of extensive community consultation and take into account comparative research into law in other jurisdictions. The proposed cause of action would ensure that Australia’s privacy protection no longer lags behind or differs greatly from their counterparts in other common law jurisdictions.

A statutory cause of action would provide a reliable basis from which the courts could decide individual cases and develop the finer detail of the law. The alternative – also considered in the ALRC report – would be to leave the development of the law fully in the hands of judges.

That is a process that causes more uncertainty and higher costs to litigants. Any judicial change to the law would also be less likely to reflect community expectations as closely as the proposed statutory tort.

The government’s freedom agenda

Unfortunately, Commonwealth Attorney-General George Brandis is already on record for his strong opposition to a privacy tort.

In 2012, Brandis labelled it a part of a “gradual, Fabian-like erosion of traditional rights and freedoms in the name of political correctness”.

It is therefore only a faint hope that the federal government will examine the proposed privacy tort on its merits and not be side-tracked by its own ideology or inevitable media opposition.

The government’s freedom agenda may be seen as standing in the way of improving privacy protection. Yet, on closer analysis, it would enhance our freedoms rather than curtail them if a right to privacy was finally recognised.

It cannot be denied that a privacy tort would limit freedom of speech. To some extent, that is precisely its point. But it would do so only where the significance of a person’s privacy demonstrably outweighed interest in free speech.

The federal government’s (now aborted) attempt to change Australia’s racial vilification laws shows its dislike for laws that interfere with freedom of speech.

Yet, as Race Discrimination Commissioner Tim Soutphommasane reminded us in this year’s Alice Tay Lecture, no freedom can be absolute, and competing rights and interests need to be balanced against one another.

Soutphommasane rightly pointed out that the conflict between freedom of expression and racial vilification is really a conflict between two freedoms – those who are subject to racial abuse and harassment are likely to have a diminished enjoyment of their individual freedom.

The same can be said about privacy laws. Such laws are intended to protect a person’s dignity and autonomy to allow each citizen to develop their individuality free from serious and unacceptable encroachment by others.

Rather than being anti-thetical to freedom, the protection of privacy – properly bounded by an enquiry into the conflicting interests of the parties concerned – creates space for all citizens to lead their lives as freely as possible.

Providing redress against privacy invasion

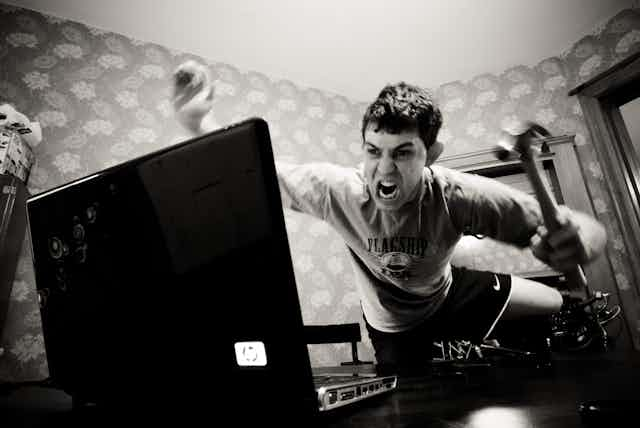

The 2011 phone hacking scandal involving parts of the British media as well as this week’s unauthorised release of explicit personal photos of female celebrities on the internet illustrate just how vulnerable our personal information has become.

It is time for the federal government to ensure that Australia’s laws protect us adequately against such and other unacceptable invasions of our privacy.

The statutory privacy tort recommended by the ALRC provides a suitable framework for balancing the interests at stake. It would give victims of gross invasions of privacy much-needed access to appropriate remedies.

Related reading: Civil action is the big stick needed to protect our privacy