On 13 November 2023, following the terrible attack by Hamas on Israel, Jürgen Habermas and three other prominent German academics released a statement condemning the rise of antisemitism in Germany. They also criticised the use of the term “genocide” to describe Israel’s response.

Israel’s military retaliation was “justified in principle”, they argued, and despite

all the concern for the fate of the Palestinian population […], the standards of judgement slip completely when genocidal intentions are attributed to Israel’s actions.

The statement generated a fierce response, with an open letter signed by numerous senior academics, many of whom had either worked with or been influenced by Habermas. They argued the statement’s “concern for human dignity is not adequately extended to Palestinian civilians in Gaza who are facing death and destruction”. Instead, they continued,

solidarity means that the principle of human dignity must apply to all people. This requires us to recognise and address the suffering of all those affected by an armed conflict.

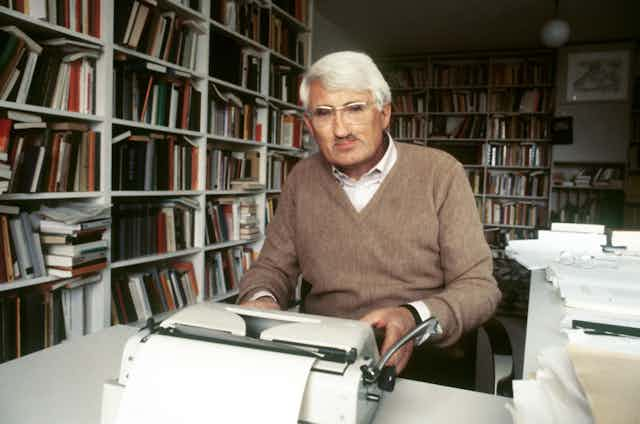

At the age of 94, Habermas had yet again inserted himself into one of the major issues of the day. The dispute over Israel’s right to defend itself, and Palestine’s right to a homeland, exemplifies some of the tensions at the heart of his astonishing philosophical journey.

So who is Jürgen Habermas? And why is he such a major public intellectual, not only in Germany, but globally?

War and philosophy

Habermas was born in Düsseldorf, in 1929, coming of age during the second world war. He joined the Hitler Youth movement and was called up to the army. But immediately after the war, and with the revelation of the horrendous Nazi atrocities, he quickly grasped the moral and practical catastrophe of Hitler’s regime.

He eventually began studies in philosophy. After completing his graduate work, he became a research assistant to Theodor Adorno at the Institute for Social Research in Frankfurt, which Adorno directed with the sociologist Max Horkheimer. Adorno and Horkheimer were influential German intellectuals who developed what came to be known as the “Frankfurt School” of critical theory.

Taking a critical stance not only towards German society and its history (Adorno famously wrote there could be “no poetry after Auschwitz”), but also towards the nature of rationality and the Enlightenment more generally, they inaugurated a research program that still resonates today.

Although Habermas left the institute after a brief period, he eventually returned to the University of Frankfurt, this time as professor of philosophy, where he remained until his “retirement” in 1994. During this period and after, he produced a remarkable array of work, which has shaped debates not only in philosophy, but in sociology, political science, history, law, cultural studies, and not least, in the broader public culture of Europe and North America.

The 18th century philosopher Immanuel Kant once described his philosophical project as driven by three questions: What can I know? What must I do? And what may I hope? That’s a pretty good summary of Habermas’s project too.

However, unlike Adorno and Horkheimer, who were sceptical about the promise of radical politics given the pathologies of modern “unreason”, Habermas was interested in the extent to which modernity was an “unfinished project”.

This sense of the unfulfilled promise of the Enlightenment shaped some of his most important ideas. I want to explore two of them here.

‘The unforced force of the better argument’

The first is what Habermas calls “discourse ethics”. The underlying idea is that the conditions required for successful communication between people prefigures a form of public reasoning that helps us make sense of the normative grounds of liberal democracy.

“Discourse” is a special form of rule-governed communication. It is oriented towards truth seeking and providing reasons to others that they could, in principle, accept. The “unforced force of the better argument”, as Habermas puts it, should carry the argumentative weight in discourse, not economic or political power.

At first glance, in a world of corrosive social media and Trumpian “fake news”, this seems preposterous. But Habermas isn’t demanding that we convert politics into a philosophy seminar. Rather, he wants us to pay attention to (what are for him) the universal and unchanging moral presuppositions of genuine communication.

If human beings are fundamentally free and equal, then certain things follow as to how we ought to treat one another. Habermas takes Kant’s idea of the “categorical imperative” – in essence, act only in ways that you would rationally want everyone else to act – and converts it into a discursive imperative.

Read more: Explainer: the ideas of Kant

What does this mean? He ties moral reasoning more closely than Kant did to people reasoning together. And so the imperative becomes: act only in ways that could be justified from within an “ideal speech situation” – a thought experiment in which communication is imagined to be free from the distorting effects of power and inequality.

Note two things about Habermas’s focus on “discourse” here.

First, he is using the thought experiment of an ideal speech situation as a way of getting us to focus on what standards we should appeal to, as opposed to unquestioningly assuming our existing ways of communicating and behaving are morally and politically satisfactory.

And second, he is linking these standards to dialogue and consensus between human beings. The right thing to do, in life as well as in politics, is, roughly, what others most affected by your actions could agree to.

Our politics is, obviously, far removed from such ideal conditions. But we can only make sense of just how distorted it is, argues Habermas, by reflecting on the presuppositions inherent in the very idea of communication itself.

Habermas’ arguments provide standards against which to make sense of the purpose and legitimacy of liberal democratic institutions. This leads to the second big idea I want to highlight.

Deliberative democracy

Like the American political philosopher John Rawls, with whom he had an ongoing philosophical conversation over many years, Habermas thought that liberty and equality needed to be reconciled through our democratic institutions.

And the more he reflected on the pluralism of modern societies, the more he saw the function of legal and political institutions as helping to bind them together.

Consensus on valid moral norms was a necessary but insufficient condition for legitimacy. Convergence on the justification of the main political institutions was also required. This led to the development of his influential “deliberative” theory of democracy, outlined in his important book, Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy (1992).

Once again, at first glance, this idea of convergence seems deeply unpromising. Aren’t disagreements about liberty and equality at the heart of some of the most polarising disputes today?

They might well be, but Habermas argues there is a deep interdependence between the kind of freedom associated with our “private autonomy”, protected by liberal rights, and our “public autonomy” as self governing citizens. But what is the nature of this interdependence?

First, for Habermas, democracy has a double structure. In civil society, (the informal sphere), citizens debate ideas and express themselves in a myriad of ways. In the more formal sphere of parliaments, courts and bureaucracies, politicians, judges, and civil servants legislate, adjudicate, and implement policies.

What is crucial, however, is that the formal sphere must remain sufficiently porous to the informal. Legal and political institutions must remain sensitive to the demands for changes emanating from civil society. Democratic legitimacy rests on striking the right balance between these different spheres.

That doesn’t mean civil society isn’t prone to corruption or capture: Habermas is deeply concerned about the impact of social media on public debate, for example. But this double structure of politics is a crucial feature of his conception of deliberative democracy.

Read more: I'm right, you're wrong, and here's a link to prove it: how social media shapes public debate

Second, unlike many contemporary political theorists, Habermas rejects any sharp distinction between liberalism and civic republicanism.

Civic republicanism has, at its core, the idea that we are only truly free when we are self-governing; that is, when we are actively participating in shaping those laws and policies that affect our most important interests. Liberalism, on the other hand, is more ambivalent about the value of political participation. What is more important is that our basic rights are protected – including the freedom not to participate in politics!

Habermas thinks there is, in fact, a deep connection between the republican and liberal traditions. Private and public autonomy are, as he puts it, “co-original”. Our basic rights – like freedom of speech, freedom of association and freedom of religion – which are highly valued by liberals – are best protected through participatory self-government.

But the specific content of our rights will need to be determined through a deliberative process. And given the deep diversity of modern societies, protecting the private autonomy of individuals is a necessary condition for the legitimate exercise of self-government. You can’t engage in a genuine dialogue with others if you are too afraid to speak your mind, or if certain voices are privileged over others.

Habermas doesn’t deny that these different aspects of democracy can come apart. However, for him, one of the functions of democratic law is to help mediate these tensions.

Criticisms

Criticisms of Habermas often start with his claim that there is an inherent logic within the structure of discourse illuminating a path towards freedom from domination. And many of these critiques bite.

Philosopher Raymond Geuss, for example, asks, “is ‘discussion’ really so wonderful?” For him, and other critics, “discourse”, does not, in fact, have an unchanging structure that enables us to discern universal rules we can live by. This is sheer assertion on Habermas’s part, or what Geuss calls the “soft nostalgic breeze of late liberalism”.

The force of the better argument appears perpetually deferred, if not drowned out, in the cacophony of our dysfunctional public sphere. Arguments for justice — from Alexei Navalny in Russia to the campaign for a Voice to Parliament in Australia – seem even less likely to carry the day than ever before.

However, in appealing to an ideal that stresses the dialogical nature of persons, Habermas provides a distinctive argument for the moral basis of democratic institutions. The ultimate validity of the underlying norms of liberal democracy rests with the participants in the discourse – you and me.

You might well disagree with him. But in doing so, you are committing yourself to a view that can’t help but draw on ideas he has done so much to put into our public consciousness.