The recent outcry in Sydney about “alcohol-fuelled violence” has many people asking whether young men are out of control, or whether alcohol, or our hyper-masculine culture, might be to blame.

Now the New South Wales Premier, Barry O'Farrell, has announced lock-outs for new customers and a cease of alcohol trading by 3am, while mandatory minimum sentences of eight years in jail will apply for fatal one-punch attacks involving alcohol and drugs.

In the context of these announcements we should remember that, despite these awful recent cases, Sydney is a relatively safe city, compared with Johannesburg in South Africa, or Ciudad Juárez in Mexico, or New York. And if we are concerned with men’s violence in Australia, the half-hidden epidemics of family violence, sexual harassment and rape are much wider problems than street bashings by strangers.

But the street violence is worrying, is more visible and has got media attention – and this has produced a debate about what’s happening among young men.

The blame game

Is this “alcohol-fuelled violence”? Drinking is often part of the lead-up to violent episodes, domestic as well as street. But alcohol can’t meaningfully be called a “fuel” of any particular behaviour. As Shakespeare knew, and modern neuroscience confirms, ethanol has complex effects. It is often a depressant, sometimes a stimulant.

In many situations it’s more likely to make you feel sleepy or ill than encourage you to hit out. It’s the circumstances of drinking, rather than the chemical itself, that we need to understand.

Can we blame “the male brain”, testosterone, or genetics? This suggests that young men are really animals, replaying a primitive world in which violence is natural, where males fight cave bears or hunt mammoths. Unfortunately some enthusiastic biologists retail such bed-time stories about violence, without knowing the historical, psychological or social-scientific evidence.

The psychological evidence is very clear. More than a hundred years of research looking for broad psychological differences between men and women have found remarkably few. The evidence, from studies involving millions of people, shows that men as a group, and women as a group, are psychologically very similar. This finding is often ignored, because it goes against so many of our stereotypes; but the evidence is strong.

So we cannot explain men’s involvement in severe violence by a “male brain”, or testosterone, or anything supposed to produce different mentalities among men and women. The different mentalities are a myth.

Can we blame a “criminal type”? Criminologists for a long time looked for such a person, but the search failed. Violence can’t be explained by a particular type of human being. Criminologists have, however, identified social circumstances in which violence is more common and patterns of violent behaviour might be learned.

These circumstances include high levels of social inequality and marginality, situations in which there is cultural emphasis on men’s dominance over women, and confrontations with police and private security.

Can we blame the media? Not in a mechanical way. Media research suggests there is no direct transmission from what people see on a screen to how they act on the street. Yet mass media are relevant. Probably the images of extreme violence – the beheadings, snuff movies, torture – are less significant than the relentless flow of images in “action” movies (which Hollywood specifically targets at young men), commercial football, other body-contact sports, cop shows, thrillers, and the like.

Those genres make up a large chunk of current popular entertainment, with a huge cumulative audience. They are built on narratives of masculine aggression, physical confrontation and dominance. So media are feeding young men narratives about how men get excitement, success and respect through confrontation. But what would make young men take up such stories?

A question of masculinity?

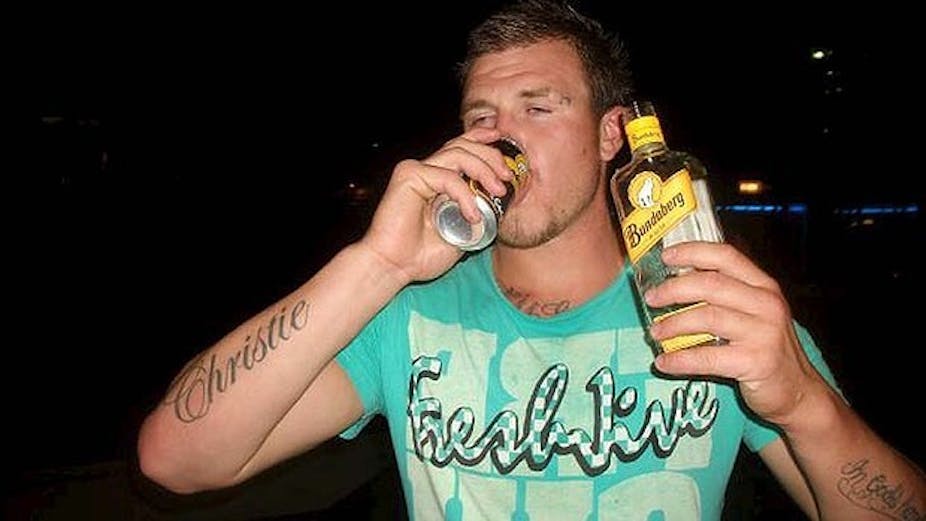

“Alcohol-fuelled violence” often involves some kind of masculinity challenge – for instance, a group of young men confronting the bouncers at a drinking venue. It’s important to note that masculinity isn’t a fixed state.

Masculinities are patterns of conduct that have to be learned. There are multiple forms of masculinity, some more honoured in a given society than others. Especially for young men, masculinity is often in question or under challenge, and the presence of an audience is important.

So we need to look hard at the social situations in which violence is happening. Some of the recent episodes are in zones of exception – places and times in which ordinary social rules are supposed not to apply, where everyday social relations are absent, such as Sydney’s King’s Cross at night.

Heavy drinking is often happening in an all-male, all-young peer group. An element of impunity, a sense that you can get away with it, is also part of the picture.

If we want to know why some young men get into zones of exception, confrontations and episodes of violence, we might ask what else is happening in their lives. Is our society giving them secure jobs? Worthwhile work to do? Models of positive relations with women? Occasions for care and creativity?

I would guess the answer to these questions, for the young men involved in street violence, is often no. But I’m not sure of it – and I don’t think our legislators are, either.

It would be a great pity if the only response to these dismaying episodes is more confrontation, this time from the government.