David Bowie’s newest album, Blackstar – released shortly before the artist’s death – has skyrocketed to the top of the charts.

It’s also become a subject of intense scrutiny by critics and fans: What was the reclusive singer’s state of mind as he approached the final months of his life? Could the album contain any clues? (Some have even speculated that the pop star delayed his death until after the album’s release.)

No one can say for sure. But when composing the album, Bowie – a master of allusion – clearly had death on his mind.

Specific references to the themes of gender and sexuality that pervade his other work are entirely absent. Instead, Blackstar’s stark depiction of death highlights a longstanding (but often ignored) symbiosis between Bowie’s creative work and the dark, morbid aesthetic of the goth subculture, a movement he inspired in the mid-1970s.

A series of inevitable deaths

Death has always been integral to Bowie’s work, and his career has been punctuated by a succession of onstage alter egos, each of whom had to be symbolically “killed off” in order to make way for the next. In the case of one of Bowie’s most outlandish alter ego – the bisexual glam alien Ziggy Stardust – the character’s narrative ended abruptly with his “Rock ’n’ Roll Suicide.”

Plagued by a variety of different troubles, other Bowie protagonists vanished with less fanfare. But their deaths seemed just as inevitable. Bowie’s gender-confused Deitrich/Garbo character – pictured on the cover of Hunky Dory (1971) – finds comfort in the belief that “knowledge comes with death’s release.”

Meanwhile, the schizophrenic Aladdin Sane (purportedly modeled on Bowie’s brother) seems to drown in his own depression, wondering whether he’ll ever be loved. In 1976, the cocaine-addled Thin White Duke seems destined, like Bowie’s fictional junkie, Major Tom (1969), to lose his grip on reality and float, untethered, into outer space.

A unique subculture emerges

Around this time, the term “goth” was becoming more and more widespread.

The word was initially coined in 1967 by rock critic John Stickney to describe Jim Morrison’s brooding personality. Later, it would be freely applied to bands that eluded characterization (most famously The Velvet Underground).

By the late 1970s, the term was used more broadly to describe a subculture that identified itself with “gothic” themes drawn from 19th-century horror literature. Visually, early “goths” – male and female – conveyed “horror” with black clothing, exaggerated black makeup, and piercings. Musically, the genre depicts isolation and despair with hypnotic rhythms, echos, and flanging guitar effects that sounded cold and brittle. An example from the period is Bauhaus’ “Bela Lugosi’s Dead” (1979), whose lyrical references to vampirism and the occult are set to a bleak repetitive musical text.

The deaths of each of these early Bowie characters – and the problems that they faced in their fictional lives – provided thematic fodder for the goth bands that followed. Siouxsie and the Banshees, The Cure, Joy Division, and Bauhaus all focused their attention on the dark recesses of the human psyche. Like Bowie’s creations, their songs similarly confronted topics like death, human suffering and isolation.

And like their Bowie precursors, early goth characters – like Siouxsie, Robert Smith and Dave Vanian – were theatrical, dramatic and challenged conventional ideas about gender and sexuality.

Meanwhile, the specter of death remained ever-present – on the surface in goth, and always in the background for Bowie as he moved from one alter ego to the next.

In Blackstar, a pop legend confronts death

The dark and disturbing imagery of Blackstar’s videos clearly draw upon gothic influences like horror and the supernatural.

The album title derives from a term used to describe a radial scar pattern found in some patients with breast cancer. Meanwhile, the lyrics identify the singer as “the Blackstar,” who instructs his listeners to “look up here, I’m in heaven.”

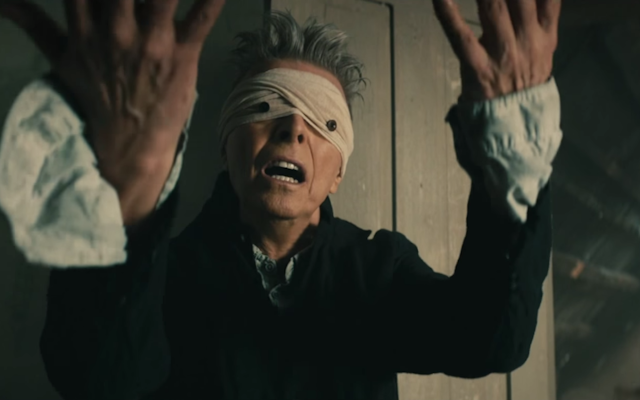

In “Lazarus,” we watch a blindfolded man who, like Lazarus, attempts to rise up from his deathbed. In “Blackstar,” we witness a woman stumble upon the jewel-encrusted skull of a dead astronaut under the gloom of a solar eclipse.

Meanwhile, in Bowie’s final videos, the characters of “the priest” and “the patient” are obvious allusions to death. In his final appearance on the music video, Bowie shepherds the patient “Lazarus” into the dark recesses of death’s closet. Combine this with Bowie’s sickly pallor and shocking physical deterioration in both videos, and it’s impossible to miss the point.

While Blackstar certainly recalls a genre that Bowie helped to nurture over 40 years ago, both goth and Bowie have changed in the intervening decades. Today, goth retains its many of its original visual qualities. But these have been adopted by newer musical genres like post-punk, metal, industrial and shock rock, dark ambient, and trip-hop.

Nearing the age of 70 and faced with the prospect of his own death, Bowie could no longer convincingly present himself as the sexually ambiguous alien being that inspired goth’s style. And why would he? Instead, he chose to embrace the “ordinary mortal” as his final persona, while imagining his own death through a vocabulary of visual signifiers drawn from the goth subculture.

This is Bowie stripped bare, and our identification with his mortality is what makes this final work both compelling and upsetting.

The day after his death, Bowie’s longtime collaborator and producer, Tony Visconti, declared on Facebook that “his death was no different from his life – a work of Art.”

Unfortunately, this time there won’t be any reinvention.