Given that the IPCC now considers that climate change is “unequivocal”, that human influence is “95-100%” likely to be the dominant cause, and that its effects are already being felt around world, it is still surprisingly difficult to bring those responsible to justice.

In terms of its ability to regulate the causes and mitigate the effects of climate change, politics alone is not working. Litigation through the courts is a powerful device that can be used to increase public awareness, pressure governments to implement and improve regulation, and ultimately to drive polluting industries and individuals to change.

There have been occasions when international bodies have considered cases regarding the effects of climate change. In 2005 an organisation representing the Inuit population in Alaska, Canada, Greenland and Russia petitioned the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. They called for an end to violations of the Inuit human rights resulting from global warming caused by unabated US greenhouse gas emissions. While this wasn’t a claim for compensation, it was an attempt to force the US to adopt emissions reduction targets, and to raise awareness of the situation.

Other examples include legal applications, by Peru and Nepal (among others), to have World Heritage Sites placed on the UNESCO “in danger” list as a result of deterioration due to climate change. These seek to impose emissions reduction targets on all parties to the UNESCO World Heritage Convention. However, the cases’ merits were never considered; an expert group was instead set up to assess the risks these sites face.

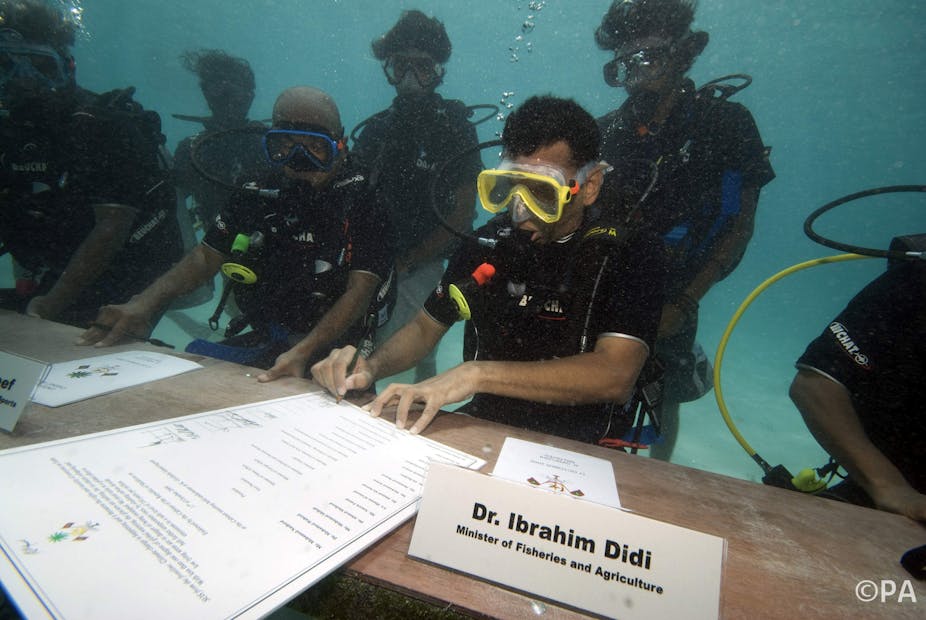

More recently, in 2011 the island state of Palau expressed their intention to seek an advisory opinion from the International Court of Justice. This would form an opinion on whether the well-established principle of international law, which requires that countries do not carry out activities within their territory that cause harm to other states, and Article 194(2) of the UN Convention of the Law of the Sea, which requires states to “take all measures necessary to ensure that activities under their jurisdiction or control are so conducted as not to cause damage by pollution to other states and their environment”, apply to the greenhouse gas emissions that cause climate change.

If, or more likely when, such an opinion is sought it will not be legally binding. But it would undoubtedly raise the awareness of the predicament faced by small, low-lying island states in the face of climate change and rising sea levels. In doing so it would increase political pressure for more urgent action.

These cases have undoubtedly provided a lever to exert political and moral pressure on governments to take climate justice seriously. But so far international law has not delivered tangible protection to those already hugely affected by climate change. And in any case, such legal actions are likely to focus on the damage caused by historic emissions – perhaps not the most effective way to help vulnerable states protect their futures.

More courts, more opportunities

The picture with respect to litigation based on national laws is not much better. These generally fall into two categories: common law tort cases (for example nuisance) and judicial reviews.

Actions brought in nuisance face the difficulty of establishing a causal link between the action and the harm. Currently it is difficult to link specific greenhouse gas emissions with specific climate change impacts. On the other hand, similar issues have been overcome in the past in cases involving asbestos and tobacco. With time, strong cases, and a sympathetic judiciary, the courts may find a way to overcome this hurdle. But this can only happen if these cases continue to come before the courts.

The claimants brought their claim for compensation under the federal common law of nuisance, but the court found that as the US Clean Air Act applies to carbon emissions, the existence of that Act prevented there being any right to claim compensation under federal common law. The court concluded that, at the federal level, the “solution to Kivalina’s dire circumstances must rest in the hands of the legislative and executive branches”. The court has however left open the possibility of a claim under state law.

Judicial review cases have largely focused on challenging awards of licences for fossil fuel exploitation. These have proved more successful but, for example, Australian cases involving open cast coal mines have failed, since the courts have been reluctant to accept that an individual coal mine is “significant” in terms of global climate change.

A US case won an important victory when the Supreme Court ruled that the EPA’s refusal to regulate greenhouse gas emissions presented an “actual” and “imminent” risk of harm to public health and the environment. Unfortunately there has been limited progress since. ClientEarth has also used judicial review to successfully challenge the permitting of new coal-fired power plants in Poland.

A legal future seems likely

So while legal systems are not currently well aligned to deal with the injustices of climate change, it’s likely that legal rulings will ultimately turn against greenhouse gas emitters. An improving scientific understanding of cause and effect should eventually provide the evidential basis required to establish liability for damage.

Running parallel, ever-stronger regulations of greenhouse gas emissions and increased legal, political and financial risk looks set to render a significant quantity of existing fossil fuel reserves “unburnable”. This triggers requirements in company law that govern risk disclosure and reporting, corporate decision making, and the valuation of company assets. In this way, company law and financial regulation should ultimately force a wide range of corporations to realign their actions with the scientific realities, and the global public interest.

Indeed, legal challenges based on established company regulations may prove far greater levers on global carbon emissions than claims through the international courts – and in the long run may do more to improve the situation of those worst affected by climate change. The recent resolution by the shareholders of Exxon Mobil, requiring Exxon to improve their disclosures in relation to climate risk, suggests that this tide is already starting to turn.