New laws to govern publishing on the internet will likely be needed in future, the chair of the UK’s biggest inquiry into media practices and phone hacking has said.

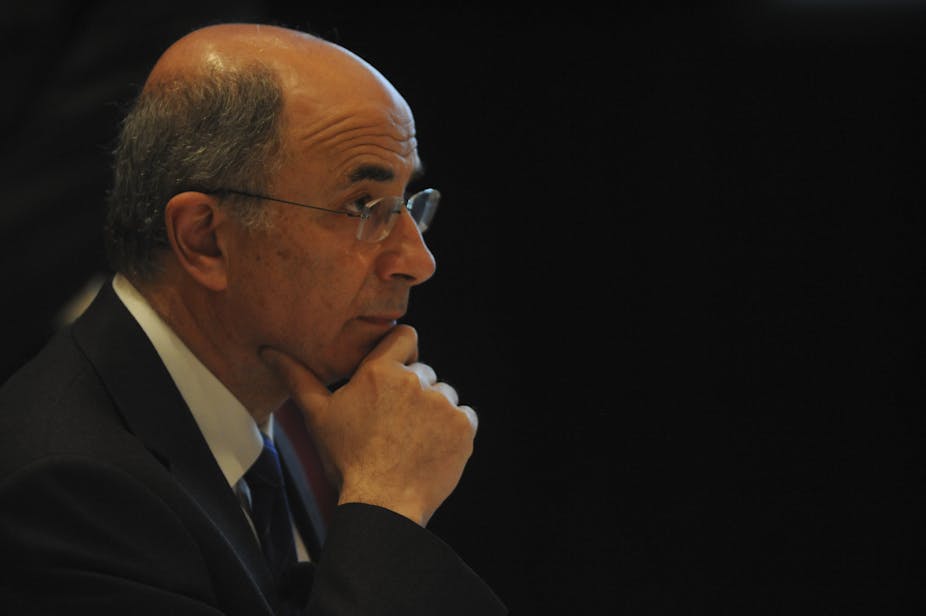

Lord Justice Brian Leveson made the comments at the UTS Privacy in the 21st Century symposium in Sydney, a week after he delivered the findings of the Inquiry into the Culture, Practices and Ethics of the Press.

His 2000 page report, prompted by the Murdoch-owned News International phone hacking scandal, has been criticised for touching only briefly on the role of the internet in the privacy debate. However, Lord Justice Leveson today devoted his entire speech to the topic.

Sir Brian noted that some aspects of existing law, such as injunctions, defamation and laws against inciting violence, had already been used to prosecute Facebook and Twitter users in the UK.

But existing law may not be enough, he said.

“While established legal norms are in many respects capable of application to the internet, it is likely that new ones and new laws will need to be developed,” he said.

“Only if we do so will we properly understand the role and values which underpin privacy and freedom of expression, the balance to be struck between them and the means to ensure that they are both safeguarded in an internet age.”

Freedom of expression is an important principle but can only truly be enjoyed if privacy is properly protected, he said.

Lord Justice Leveson declined to elaborate on how new laws to govern internet publication might look, saying only that creative thinking was required.

He noted that Australia’s Convergence Review recommended media outlets should be regulated regardless of platform and that such laws might be applied to outlets that have an annual revenue of $50 million and 500,000 Australia users per month.

“The difficulty, of course, is that this would not include Google,” he said, adding that some bloggers deliberately place their servers outside the jurisdiction where different laws apply.

Existing law may eventually encourage internet users to modulate their own behaviour.

“Just as it took time for the wilder excesses of the early penny press to be civilised, it will take time to civilise the internet,” he said.

But even in the UK – which, unlike Australia, has a tort of privacy – recent events such as photographs of Duchess of Cambridge Kate Middleton on holidays showed that “nothing, it seems, was off limits.”

“Given the historical failure to develop limitations on incursions into privacy by the media, it might reasonably be said that it is difficult to assume that any such limitations might evolve in so far as the internet is concerned,” he said.

“It is much more plausible to assume that any such limitations will require some type of intervention.”

Sir Brian noted that definitions of privacy were changing, with many freely posting private information and pictures of themselves on social networks. However, some people, especially young people, may not yet fully realise the risks involved with doing that, he said.

John Hatzistergos, adjunct professor in the UTS school of law and former NSW Attorney General for NSW until 2007, told the symposium that “if there is to be a tort of privacy, the threshold must be extremely high.”

Politicians still need to be held to account but victims of tragedy should be especially protected from media incursions into their privacy, he said.

Professor Michael Fraser, director of the UTS Communications Law Centre, called for a tort of privacy in Australia, even though existing laws such as breach of confidence rules can be used to protect people’s rights.

“We need a tort of privacy if, for no other reason, that privacy deserves to be called privacy,” he said, adding that a statutory tort could also afford the creation of a public interest defence that media could use to protect a free press.