Australia is pivoting its economy away from resources like coal and iron ore, but are there other commodities we can bank on to take up some of the slack? In this “future commodities” series we explore the economic future for commodities we’ve always relied on, and some we haven’t.

Australia has an opportunity to capitalise on the increasing global demand for lithium batteries by developing recycling systems and creating models for leasing the resource.

Lithium is the third element in the periodic table and the lightest classified as a metal. This makes it a good choice in battery applications needing lightweight energy storage. Lithium-ion batteries are now increasingly common in smartphones, electric vehicles and indeed Tesla powerwalls, the first of which was recently installed in Australia.

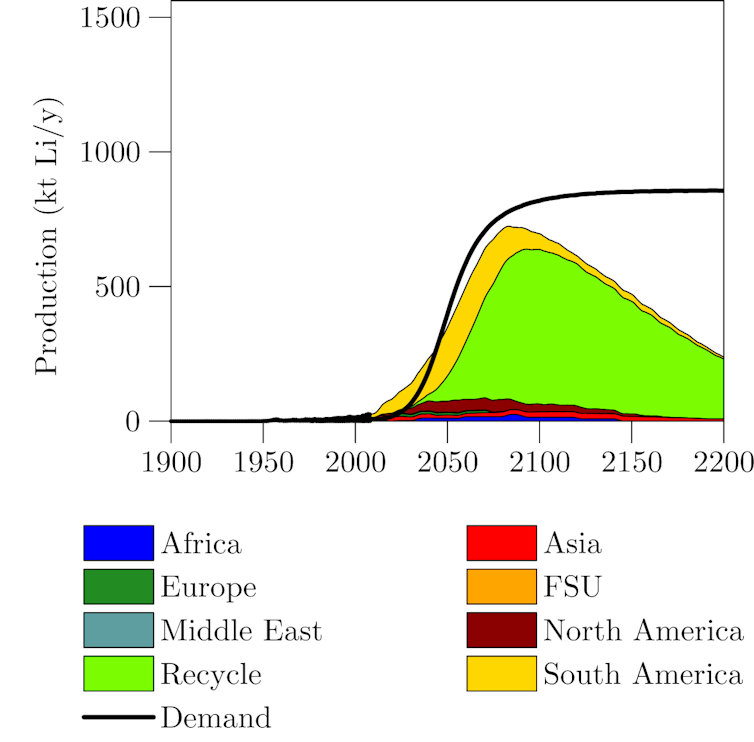

Because of this rising demand, Lithium is considered to be a “critical” mineral by many countries. Currently, global demand is over 32 thousand tonnes per year. This is predicted to rise to between 80 to 280 thousand tonnes by 2030, with a mid-range forecast shown in the figure below.

The variation in demand forecasts over the next 15 years depends on the rate of uptake of electric batteries for vehicles and storage. They are also foreseen to continue rising through to 2050 and beyond. However, new battery technologies which use metals other than lithium (for example zinc-air or zinc-bromine) can be expected to increase their market share.

New opportunities for innovation

In order to meet future demand, recycling of lithium will also need to rise significantly. A report by the International Resource Panel shows historical lithium recycling rates are at less than 1 percent. Current challenges to commercial recycling include limited volumes of waste batteries (as many are still in the useful phase of their life) and a lack of investment for piloting suitable recycling technologies.

However businesses and government must start planning now for collection and processing of this future waste stream, to ensure pathways are in place for reuse and recycling of what is a hazardous, yet valuable, waste. In particular, as lithium batteries rise past 50,000 tonnes per year in the waste stream by 2030, the need rises for developing efficient sorting systems to isolate these batteries and moderate the risk of fire.

Without the requisite infrastructure for local recycling, the valuable metals in batteries will not be recovered, yet environmental impacts rise both at home and abroad, as for other electronic waste.

Looking to the future, firms in Australia might also consider new business models such as leasing instead of selling lithium. This provides a mechanism for capturing value at multiple points along the supply chain (mining, battery manufacture, use, recycling) rather than relying on yesterday’s ‘dig-more sell-more’ model for national prosperity.

For example, by teaming up with battery manufacturers, Australian companies could be the first link in a green supply chain. This would involve mining lithium, processing it for use in batteries, leasing the lithium-in-batteries to users of power storage, then offering a collection chain for recycling.

In effect, this sells the access to lithium as a service, whilst promoting resource stewardship. Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull suggested something similar for the uranium supply chain.

Who will supply lithium in future?

When asking ‘where will all the lithium come from?’, it’s important to bear in mind that not all sources of lithium are equivalent. Lithium generally comes from either hardrock mining, such as in Australia, or the evaporation of salt lakes (or brines), such as in Bolivia and Chile.

Due to the differences in chemistry, it is easier for lithium from brines to go into lithium-ion batteries and for that from hardrock to be used for glasses and other applications. Putting hardrock lithium into batteries requires a further conversion process which adds to costs.

Several Australia operations are active in this space, Talison Lithium mines hardrock lithium at Greenbushes and has outlined a concept for a local plant to process to ltihium carbonate for use in batteries and further research and development of conversion processes to bring down costs, this would improve Australia’s position in supplying global markets. Recent price rises in lithium have also prompted Western Australia’s Mt Cattlin mine to reopen.

While Australia was the largest producer in 2014, South America is the hub of future growth. Chile is banking on a future boom to strengthen the health of its mining sector which has until now been focused on copper and indeed has established a National Lithium Commission. Also in South America, Bolivia is sitting on huge salt flats containing lithium, but has not yet exploited them to any significant extent. In these emerging mineral economies in particular, as with many large resource development projects, social and environmental impacts must be carefully managed.