The case of six year old Oshin Kiszko who was ordered by a judge to undergo chemotherapy for his medulloblastoma – the most common type of malignant brain tumour in children – against the wishes of his parents, raises some pertinent questions.

Among these is how parents can better be helped to make decisions about whether or not their child should undergo aggressive treatment for their cancer.

After the shock of a brain cancer diagnosis, families will understandably first ask: “Will my child survive?” While modern medicine can now go some way to answering this question, the one that shortly follows is just as important: “What future does my child face?”

Cancer in a child’s brain has the potential to impact their overall future health and cause long-term disturbances to the central nervous system of survivors.

These include cognition and communication difficulties that, if not addressed, can affect academic achievement and social skill development; impacting interpersonal relationships, job successes and overall life quality. Early intervention in neurocognition and communication can lessen the impact of such difficulties on survivors.

How brain cancer disrupts development

Cancer is the leading cause of death, after accidents, in children aged under 15 years. In Australia, brain cancer is the most common form of solid cancer in children and accounts for a quarter of all cancers.

Treatment and technology advances mean children now have a much better chance of surviving brain cancer. With survival rates of childhood cancers at 83%, the majority can enjoy full and satisfying lives.

But some may struggle with cognitive and communication difficulties, including with their IQ, visual-perceptual skills, attention, memory, vocabulary, grammar, social and problem solving skills.

Many factors impact long-term outcomes in these areas. There are the direct effects of cancer on the delicate structures of the brain and the pressure inside the skull caused by the tumour. Others include the length of time the cancer has been growing in the brain, the child’s age, how aggressive the cancer is, its symptoms, and the treatments required to combat it.

Children diagnosed with brain cancer at a younger age are more at risk of long-term cognition and communication difficulties. This is because the developing brain is particularly vulnerable to cancer.

Historically, it was believed that the brain’s ability for change (neuroplasticity) meant children could make a rapid and full recovery after brain cancer treatment. But recent research has shown cancer can cause long-term changes to brain structure and function. The effects of treatment can also leave a permanent mark.

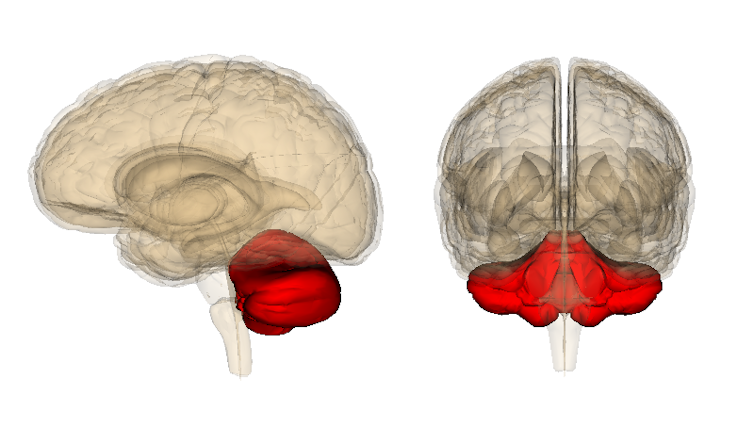

Most at risk are the processes of acquiring new skills in cognition and communication during development. Radiation and chemotherapy drugs can have harsh effects on neurodevelopmental processes, such as myelination, which begins before birth and continues into adolescence.

During this time, brain neurons are being covered with myelin – an essential protective substance that increases the efficiency and speed of signals around the brain. Disruption of this process reduces white matter volume in the brain, which has been directly linked to cognitive and communication deficits.

Children under three are considered most at risk due to rapid ongoing myelination processes that can in some cases go on until seven years of age.

The cerebellum – the most common site for childhood brain cancer – is intrinsically fragile as its nervous tissue takes a particularly long time to develop. Disruption of this has been linked to behavioural disturbances such as autism.

Survivors can have difficulties that range in severity: from mild to profound impairments, that can severely disrupt their quality of life. Besides struggling in areas such as attention and problem solving, studies have also noted social language deficits, such as not understanding jokes, hidden meanings, and sarcasm.

A study of 110 children with medulloblastoma who had received reduced dose radiation and chemotherapy treatment, for instance, reported progressive declines in both intelligence scores and academic attainment measures some years after treatment.

Treatment is available

It can often take years for subtle deficits to become noticeable in survivors of brain cancer. They can show up when children start school, make new friends, transition to high school, navigate social media, adapt to teaching styles and language of the classroom and go for their first job.

Even if children don’t show signs of these difficulties at discharge from hospital and rehabilitation, they are still likely to lag behind their peers. That is, if they are not routinely monitored throughout development and provided early and ongoing intervention and support.

Many non-medical intervention programs for cognitive and communication deficits following brain cancer survival show excellent success.

Approaches include providing general resources and strategies for integrating into school, regular surveillance and monitoring to map appropriate recovery processes, cognitive behavioural training programs, peer-group programs, skills-based training, vocabulary and word learning interventions, social skills programs and peer buddy systems.

Health professionals have an opportunity to ensure optimum quality of life for these children, who now have a much better chance of surviving brain cancer thanks to modern medicine and research.

Improving the lives of survivors now shares attention with the vital work dedicated to improving cure rates in childhood cancer research, and more positively and effectively addresses the concerns of parents who hope for a normal and bright future for their child after cancer.