Political participation in Australia will soon be about hope – and the transformation of citizenship engagement in this country.

Here is why.

Traditionally, Australian political participation was centred on, and supported by, the electoral system, political parties and major political organisations.

Most media commentators tend to focus on the electoral system as the main way of consolidating political support and bringing about change. They assume citizens make political choices to participate and/or express themselves based on rational, self-interested, often economic, calculations.

When citizens have been mobilised it has usually been done by unions, political parties and environmental organisations. These have the resources, skills and experience to undertake mass protests.

The Your Rights at Work campaign undertaken by Australian unions in 2006-07 is an example. Yet this was an expensive campaign, centred on television advertising that cost about A$20 million.

Over the past decade, new kinds of political organisation have emerged. Enabled by the internet, movements such as GetUp! and new forms of citizen mobilisation don’t require formal organisations.

Many causes come together

March in March was different. It revealed itself to be organised by grassroots campaigners with few or no organisational affiliations. More importantly, it used social media, mainly Facebook, to organise people to attend protests.

The March in March campaigners claimed in very general terms that it was:

…to protest against government decisions that are against the common good of our nation.

At the event in Sydney last weekend, I observed a range of issues – from shark culling to refugees to public service job cuts – on mostly handmade signs. While several flags were flown representing unions and small political parties, I was struck by the lack of co-ordinated political messaging in the signs or even among the rally speakers, compared to past rallies with higher profiles.

The largest rallies in Australia have tended to be on single issues; they focused on distinct political outcomes. For example, the goal was to “stop the war” and bring Australian soldiers home, in either Vietnam or Iraq, or to defeat government legislation, such as WorkChoices.

Other interest organisations have also used large rallies and protest marches to seek specific political outcomes. The Iraq war rallies in February 2003, however, were the biggest ever: protesters numbered 500,000 nationwide.

Mainstream media reported accurately on the high numbers of Iraq war protesters. Many also highlighted the diversity of participants. But it was easy for media and government to discount citizen protest as an expression of political will, especially when the protest failed to achieve its desired outcome.

Defying conventional understanding

Now it has become more difficult for mainstream media to understand a protest that does not focus on a distinct political outcome and a single issue. Many have found it difficult to sum up what March in March was about. What was the issue? What (political outcome) did protesters want? Who was even there?

The answer is that March in March has much in common with protests such as Occupy, which emerged in the United States, the Indignados in Spain and the Gezi protests in Istanbul. All these popular protests were harder to pin down using traditional lenses for understanding interest group and political mobilisations.

We need to turn to new theoretical ideas that try to explain contemporary forms of mobilisation. Political scientists Lance Bennett and Alexandra Segerberg suggest that “connective action” is steadily replacing traditional, organisation-led collective action. The two forms of connective action are:

“Digitally enabled connective action” involves loosely tied networks that support actions and causes around a general set of issues. Participants use social media to personalise their engagement on their own terms and connect with like-minded others. In Australia, online campaigning organisations like GetUp and the Australian Youth Climate Coalition are examples of this.

“Crowd-enabled connective action” is where social media platforms become the most visible and integrative means of organisation. The actions of campaigners gain scale and publicity through these social media networks, which are organisational hubs, along with the role of individuals in activating their own social networks. Bennett and Segerberg describe the Occupy protests and Indignados here, but March in March shares much of these characteristics.

March in March’s focus on social-media-based organising, often among existing offline friend networks, is what is least understood in media commentary.

Storytelling moves the masses

I can add another theoretical dimension helpful for understanding new forms of political participation and protest mobilisation: the role of emotions and storytelling. Sometimes a protest does not have an intended political outcome. It is more about the public expression of a shared set of emotions – anger, joy, hope, empathy and even humour.

Campaigners increasingly use storytelling as a strategy to develop citizen empathy with a cause. The idea is to make it easier for people to personalise and relate to a cause, as a prior condition for acting collectively.

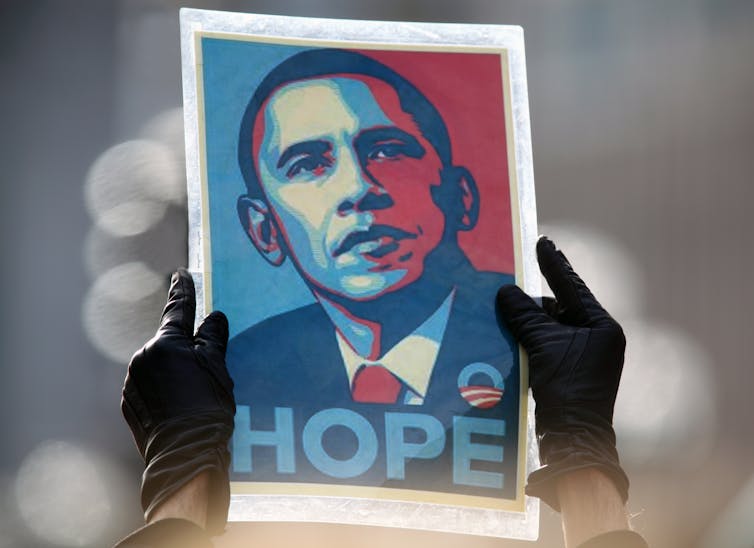

Think about the initial Barack Obama’s initial presidential election campaign and its focus on “hope”. Maybe March in March was important alone for providing a space for people to express their emotions, their indignation about a whole lot of things. This is much harder to understand for pundits focused on the existing party/electoral system, rational actors and distinct outcomes.

It is hard to know what will happen next with March in March, or how commentators and existing political organisations will respond. Maybe not much will happen at all. There are several factors, though, that we should start to understand more as a result.

Political mobilisation can increasingly happen without formal political organisations. Crowd-based, personalised networks on social media provide citizens with the resources, skills and political experience needed to organise protests.

Existing organisations can and ought to be part of these organising processes. But to do that they will need to understand emotions and new expressions about politics that do not fit the rational-voter model. They must also learn that top-down directives focused only on single-issue, political outcomes may not be the best way to engage everyday citizens.